The Department of Community Services coordinates the activities of nine different sub-groups that are dedicated to providing participants with vital public services at our event. We work to educate our citizens about important environmental and social issues, and we facilitate the annual Town Meetings. We place theme camps on the playa and help to design the social infrastructure of Black Rock City. We welcome volunteers to Burning Man and conduct workshops designed to educate our staff members about volunteerism. We also host events and gatherings within our organization. This is the department that nurtures the social network that makes Burning Man possible. We have very few paid staff members, but we employ approximately 500 volunteers annually.

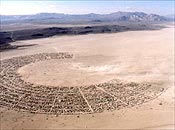

This focus on the social context of participation goes back to the origins of Burning Man when volunteers were asked to help build and burn the Man on Baker beach in San Francisco. As our event became a full-fledged city in the Black Rock Desert, we began to organize communal efforts in support of this new civic mission. Black Rock City’s Lamplighters were founded in 1994 because participants needed landmarks to guide them in an increasingly complex environment. By 1995 we created a city map that identified the location of theme camps and public services offered by other departments of Burning Man. However, community services really blossomed in 1997 with the addition of Greeters and Playa Information (formerly known as Check Point Salon).

Today, the Greeters help perfect the art of “instant acculturation”. In welcoming everyone who passes through our gate, they provide attendees with important public information. And, by personally greeting everyone, they help thousands of strangers to feel at home. We have discovered this interaction is vital in transforming individual participants into people who felt a common bond with their fellow citizens.

Today, the Greeters help perfect the art of “instant acculturation”. In welcoming everyone who passes through our gate, they provide attendees with important public information. And, by personally greeting everyone, they help thousands of strangers to feel at home. We have discovered this interaction is vital in transforming individual participants into people who felt a common bond with their fellow citizens.

Furthermore, once people arrive, our playa information resources help participants to find their friends, to orient themselves and discover where they might like to camp. Playa Information answers thousands of questions that people ask about a novel environment. During the formative period, what were called “villages” also began to spontaneously appear in our city. These arose from some participants’ desire to share resources and build communities within our city that were based on shared interests and needs.

Community services helped to locate these villages. These first “districts”, each with a distinctive flavor and tone, helped to give Black Rock City the multi-faceted personality of a real metropolis. At this same time, we also began planning for wheelchair accessibility. As a result, the disabled population of our city has steadily grown.

In 1998, we added Recycling and Earth Guardians to our city’s services. As Black Rock city grew, our impact on the playa and the surrounding desert became a very important concern. It was during this era that we embraced a Leave No Trace ethic. We needed to inform and educate participants about environmental issues. Our community was now turning its eyes outward toward a larger world. Community services responded by gathering together more volunteers, founding leadership roles, and organizing more extensive email lists. Burning Man Recycling and the Earth Guardians have helped to protect the desert and heighten public awareness concerning the environment. They’ve helped to impart the lesson that each participant is directly responsible for protecting our desert home. We also worked to develop areas for families with children who camp together and created a special zone for people who wanted to employ alternative energy technology.

This past year both Kidsville and the Alternative Energy Zone Village achieved complete autonomy. In fact, most of the citizen groups that shelter beneath the umbrella of community services are self-organized. Some receive financial aid and use other resources provided by our Project, and we work hard to help coordinate these activities and engage them in a civic mission. But all of these groups are essentially communal in character. They are not departments of a bureaucracy, so much as associations of like-minded people who share ideals and love to work together. We have tried to turn communalism – the urge to associate with people whom we know – into a movement that serves a larger public – the many thousands of our fellow citizens we do not know.

This past year both Kidsville and the Alternative Energy Zone Village achieved complete autonomy. In fact, most of the citizen groups that shelter beneath the umbrella of community services are self-organized. Some receive financial aid and use other resources provided by our Project, and we work hard to help coordinate these activities and engage them in a civic mission. But all of these groups are essentially communal in character. They are not departments of a bureaucracy, so much as associations of like-minded people who share ideals and love to work together. We have tried to turn communalism – the urge to associate with people whom we know – into a movement that serves a larger public – the many thousands of our fellow citizens we do not know.

Community Services received its current name in 1999. At that time, its participation in the planning of Black Rock City grew to include many citywide issues, such as several zoning questions. How could large-scale sound be managed without stunting creativity or freedom? In 2001 we located large-scale sound installations at the ends of our city, at two and ten o’clock, with speakers facing outward onto the open playa. This positioning significantly lessened the unwanted effects of sound and we’ve received few complaints. Where should our portable toilets be placed, and how might this be done in a way that was convenient for participants, but allowed easy cleaning? This year we massed our porta-potties in larger banks at locations in the middle of our city. We also installed banks of portable toilets on the open playa. The result was an enormous success. These toilets remained clean throughout the event. How could we prevent participants from clogging these toilets with MOOP (matter out of place) that interfered with toilet servicing? Early in the year Burning Man undertook a public information campaign. Its memorable motto: “If it wasn’t in your body, don’t put it in the potty”. This message was reiterated many times and repeated by our Greeters as people entered our city. The response was enthusiastic and there were no interruptions of service in 2001. Burning Man has learned that good citizenship primarily depends of good communication, and we have organized to do this. We have also learned that many social conflicts can be solved by zoning and placement. Because we reinvent our city every year, we possess an advantage that other cities lack. As planners, we try to listen very carefully to participant concerns, and we are always prepared to change things.

The single greatest challenge confronting community services in 2001 (and all of Burning Man) was how to manage the growing amount of information that we need to do our job. Part of the solution came from the technical development of the way we process information, and part came from the leasing of office space for year-round operations. The missing link was more trained staff. We had to create more teams and find more people to work with us year-round. Early in 2000, we began to expand our volunteer infrastructure. Ironically, many participants had been trying to join Burning Man for years. They were on the outside knocking, but could not find the door. Those of us inside could hear them knocking, but didn’t know how to let them in. We began build doorways to solve this problem. In 2001, each department within the Burning Man organization used a Volunteer Coordinator to help incorporate more people who wanted to help. Training, volunteerism and open communication spanning departments became the common thread between community services and other departments.

The single greatest challenge confronting community services in 2001 (and all of Burning Man) was how to manage the growing amount of information that we need to do our job. Part of the solution came from the technical development of the way we process information, and part came from the leasing of office space for year-round operations. The missing link was more trained staff. We had to create more teams and find more people to work with us year-round. Early in 2000, we began to expand our volunteer infrastructure. Ironically, many participants had been trying to join Burning Man for years. They were on the outside knocking, but could not find the door. Those of us inside could hear them knocking, but didn’t know how to let them in. We began build doorways to solve this problem. In 2001, each department within the Burning Man organization used a Volunteer Coordinator to help incorporate more people who wanted to help. Training, volunteerism and open communication spanning departments became the common thread between community services and other departments.

Throughout the year, Community Services is dedicated to keeping our organization’s staff members connected with one another, and in touch with our participants — the people who make our city real. Every year, we hold quarterly meetings and gatherings to educate and thank all of our workers. We plan barbecues in order to welcome new people. We organize Town Meetings in which we explain what we’ve done and listen to what everyone has to say. The AfterBurn report is a cross-departmental effort to enlarge and improve this continuing dialogue. Burning Man is an experiment in the formation of community. We believe that radically individual and free self-expression is the spark that ignites Burning Man. But we also believe that communion and cooperation with other people is the flame that sustains it.