Spirituality and Community

The Process and Intention of Bringing a Temple to Black Rock City

By John Mosbaugh aka Moze

Out of the desert grew a ritual,

a celebration,

a participatory moment

Out of the moment grew a need

A need fulfilled by a temple

A place to let go,

to remember,

to celebrate

The temple became a tradition

It grew from the playa,

from the temporary city,

from the culture

Its methods were ours,

its tradition was ours

It became a part of our city

And a part of us. – Jess Hobbs

It is no mistake that Black Rock City is laid out the way it is. Changes to the City map have been made in the last 25 years to accommodate changing population, address new civic needs and create additional spaces for citizens to gather, be they Center Camp Café, the Plazas or the Man Pavilions. Rod Garrett has discussed at length the evolution of the city layout and with this evolution has come experimentation that has been lauded as revolutionary, organic and even fit for settlements on other planets.

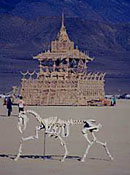

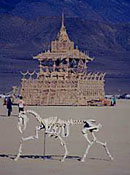

Part of this process has been the appearance of Burning Man’s Temple. David Best and Jack Haye brought their Temple of the Mind to the playa in 2000, a structure that would become the first of a long line of Temples. When their friend and fellow Temple builder, Michael Hefflin, tragically died in a motorcycle crash prior to leaving for Burning Man, once on playa, the art installation became a memorial to him.[1] David and Jack both talk about how Black Rock City citizens had a spontaneous reaction in the Temple and began leaving remembrances to people they’d lost. In 2001 David and Jack brought the Temple of Tears also called the Mausoleum, and the tradition of the Temple at Burning Man began. There has been a Temple every year since; David Best being the lead artist for half of them to date, with the other Temples built by a wide range of artists.

Part of this process has been the appearance of Burning Man’s Temple. David Best and Jack Haye brought their Temple of the Mind to the playa in 2000, a structure that would become the first of a long line of Temples. When their friend and fellow Temple builder, Michael Hefflin, tragically died in a motorcycle crash prior to leaving for Burning Man, once on playa, the art installation became a memorial to him.[1] David and Jack both talk about how Black Rock City citizens had a spontaneous reaction in the Temple and began leaving remembrances to people they’d lost. In 2001 David and Jack brought the Temple of Tears also called the Mausoleum, and the tradition of the Temple at Burning Man began. There has been a Temple every year since; David Best being the lead artist for half of them to date, with the other Temples built by a wide range of artists.

This article explores the serious nature of the Temple and its cosmological importance as part of Black Rock City and as part of our shared Burning Man Culture. It discusses artistic and skillset competence as well as what part volunteers take in the process of a Temple build and how that is different from most other large scale art installations.

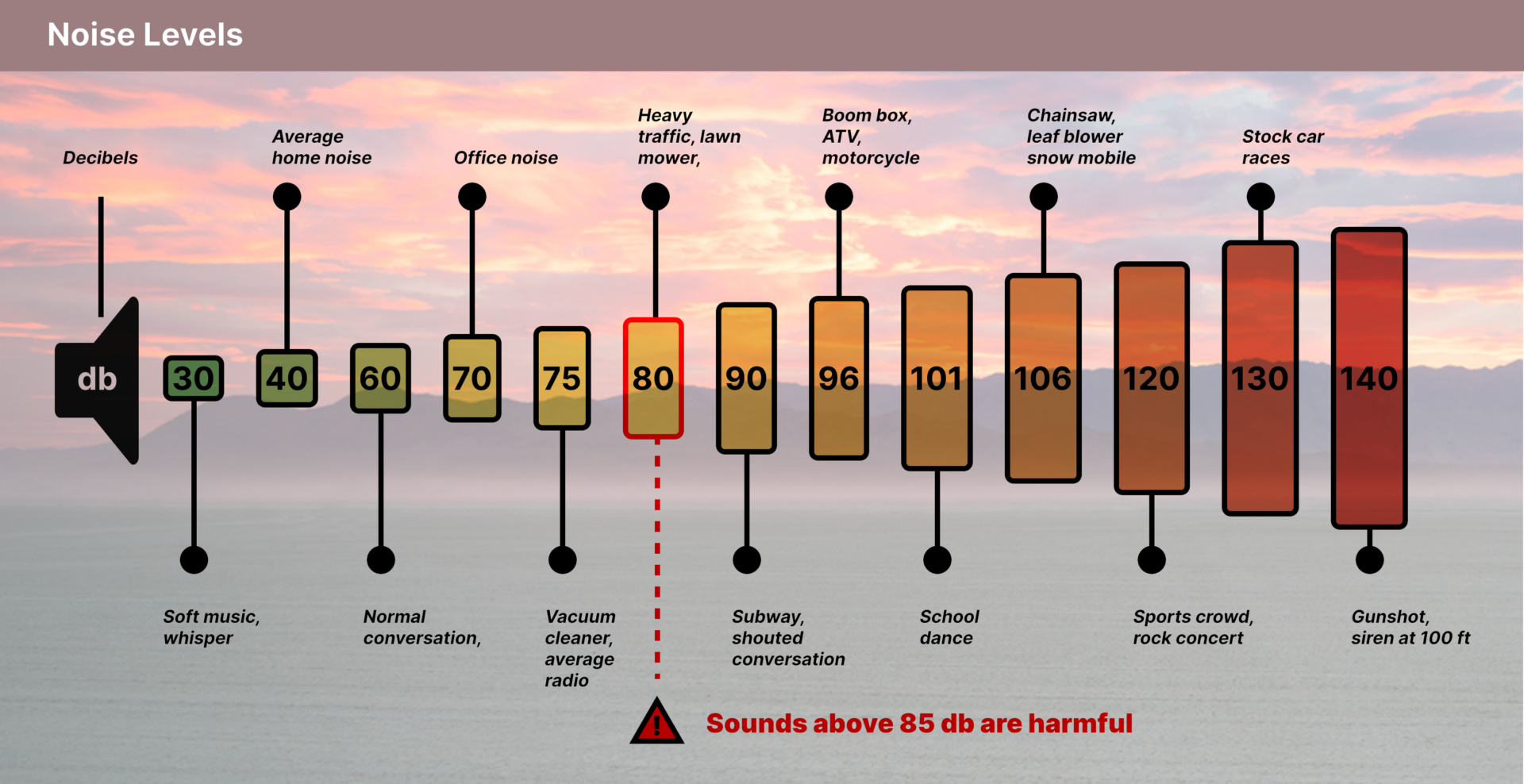

Burning Man takes the Temple seriously, and while just about everything at Burning Man is amplified both figuratively and literally, the Temple is also amplified, but not with booming music and wild ecstatic dancing or with art cars that slither along the desert floor or with other lunatic cacophony. While the Temple is something that does reflect the mad masquerade and joy of our community, it does so with sacredness, solemnity, a sense of remembrance, grief and renewal that can appear as a stark contrast to the rest of the event. It is that contrast that helps to define the Burning Man community as anything but one dimensional.

Other tangible representations of the Burning Man ethos such as Burners Without Borders and Black Rock Solar also serve the purpose of defining our community. We are very much about absurdity and expression, but also we are deconstructing prevailing ideologies of what is “normal” and creating postmodern expressions of service and civic duty with a common theme of healing ourselves and the planet we inhabit.

Other tangible representations of the Burning Man ethos such as Burners Without Borders and Black Rock Solar also serve the purpose of defining our community. We are very much about absurdity and expression, but also we are deconstructing prevailing ideologies of what is “normal” and creating postmodern expressions of service and civic duty with a common theme of healing ourselves and the planet we inhabit.

Artists who build Temples in Black Rock City are not just building a large scale art project. They’re creating something for the community and fulfilling a civic need as caretakers of that venerable space. One of the first questions one should ask themselves if they want to propose an idea for a Temple is not “WHAT am I doing this for?” but rather “WHO am I doing this for?” from what I have ascertained after talking with some of the artists who have built Temples at Burning Man.

Structure of Passage and Hierophany of Black Rock City

A long trail of rites and initiations [2] lie along the central spine that begins just off the highway pavement and on to Black Rock Desert. Pilgrims to Burning Man move through porticos of the Gate, up Black Rock City’s entrance road flagellum, past Burma Shave signs that educate the anticipation-drenched denizens in carnival conveyances with values and initiations, up through the Greeters station and into Black Rock City proper. Once inside the circle streets of the City, the backbone continues through Center Camp and through Center Camp Café where you are presented with a choice of staying where you can still purchase things like coffee and ice and can be entertained (or entertain). Or you may, hopefully, continue on your journey.

A long trail of rites and initiations [2] lie along the central spine that begins just off the highway pavement and on to Black Rock Desert. Pilgrims to Burning Man move through porticos of the Gate, up Black Rock City’s entrance road flagellum, past Burma Shave signs that educate the anticipation-drenched denizens in carnival conveyances with values and initiations, up through the Greeters station and into Black Rock City proper. Once inside the circle streets of the City, the backbone continues through Center Camp and through Center Camp Café where you are presented with a choice of staying where you can still purchase things like coffee and ice and can be entertained (or entertain). Or you may, hopefully, continue on your journey.

Moving along the walkway from the Café, you encounter the Keyhole; an imaginary last point before you step across the Esplanade into an unknown realm where nothing but art awaits you. If you choose to wander up the spired promenade to the Man you will reach what has been called the “Axis Mundi” of Black Rock City. This concept has been discussed by Lee Gilmore in her book Theater in a Crowded Fire [3] and on the Burning Man Blog where she writes, “The placement of the Man at the BRC’s center readily evokes what historian of religion Mircea Eliade called the axis mundi-a symbolic manifestation of the sacred center of the cosmos and the location of hierophany-the eruption of the sacred into the profane world.”[4]

Eliade and Arnold Van Genep figure heavily in the ontological conception of the layout of Black Rock City. 2003’s theme Beyond Belief was born partially out of Eliade’s (and Rudolf Otto’s) writings[5],[6] and 2011’s theme, Rites of Passage, drew heavily from Van Gennep’s book [7] of the same name. These ideas are integral to the intellectual foundation of the layout of Black Rock City that Larry Harvey has noted is “open in the front, open to infinity”.

Eliade and Arnold Van Genep figure heavily in the ontological conception of the layout of Black Rock City. 2003’s theme Beyond Belief was born partially out of Eliade’s (and Rudolf Otto’s) writings[5],[6] and 2011’s theme, Rites of Passage, drew heavily from Van Gennep’s book [7] of the same name. These ideas are integral to the intellectual foundation of the layout of Black Rock City that Larry Harvey has noted is “open in the front, open to infinity”.

The spot along that grand promenade that stands as the last large gathering point before reaching the sprawling “wholly other” outer playa, is the Temple, beyond which are a scattering of projects out to the trash fence and that symbolic infinity. The Temple is at the edge of where we bring order to chaos. It is where our community goes to unburden themselves.

Why is this talk of cosmology important? We know how to get to the Temple from the highway.

Burning Man is known as one of the biggest parties on earth. It is also well known as one of the pre-eminent places for public art, large sculptures, art cars, participatory experience and alternative culture. However Burning Man is not just an art gallery, a rave, a camping trip or a place to discover something new about yourself. It is not just a hopeful phenomenon or some incarnation of a Dionysian festival. It is the sum of all these, and many other things. There was a time when Burning Man was just a weeklong event in the desert, but that is no longer the case. It’s now something that exists throughout the world, appearing in many different iterations with different purposes as organizations such as Black Rock Arts Foundation, Burners Without Borders, Black Rock Solar, the Burning Man Project or in the Regionals. These entities all share a common ethos and shared community values, even if we are a diverse bunch.

Burning Man is known as one of the biggest parties on earth. It is also well known as one of the pre-eminent places for public art, large sculptures, art cars, participatory experience and alternative culture. However Burning Man is not just an art gallery, a rave, a camping trip or a place to discover something new about yourself. It is not just a hopeful phenomenon or some incarnation of a Dionysian festival. It is the sum of all these, and many other things. There was a time when Burning Man was just a weeklong event in the desert, but that is no longer the case. It’s now something that exists throughout the world, appearing in many different iterations with different purposes as organizations such as Black Rock Arts Foundation, Burners Without Borders, Black Rock Solar, the Burning Man Project or in the Regionals. These entities all share a common ethos and shared community values, even if we are a diverse bunch.

What we have in Black Rock City is a microcosm of humanity. Within this microcosm is what M. Eliade called a profane or mundane world; meaning that which is not sacred. In our realm of Black Rock City, we have plenty of cacophony, satires of every known aspect of the world we live in, fantastical art, a critical mass of events espousing our shared concern and curiosity, and a community all living together for that week to cross pollinate each other with our ideas, aspirations and evolutionary inclinations.

The theory goes that as societies mature, and their intellect develops, mythologies are created to explain the human condition. Larry mentioned this in his Viva Las Vegas speech as we’ve “learned that we need myths and stories that can tell us who we are. [We’ve] learned that we need unities of time and place, a coherent theatre in which to act out life’s drama: a place you can belong to. The prospect of such things, this idea of a greater home on earth, is extremely attractive to human beings.” [8] From myths that we create springs Eliade’s concept of hierophany [9]; the creation of sacred spaces. Alexei Lidov [10] further suggests that the creation of sacred spaces at first happens because of what he calls “heirotopy” the “creation of sacred spaces regarded as a special form of creativity,” Lidov’s idea is that the hand of man creates, influences and brings into existence a place where “Every sacred space implies a hierophany, an eruption of the sacred that results in detaching a territory from the surrounding cosmic milieu and making it qualitatively different”.

The theory goes that as societies mature, and their intellect develops, mythologies are created to explain the human condition. Larry mentioned this in his Viva Las Vegas speech as we’ve “learned that we need myths and stories that can tell us who we are. [We’ve] learned that we need unities of time and place, a coherent theatre in which to act out life’s drama: a place you can belong to. The prospect of such things, this idea of a greater home on earth, is extremely attractive to human beings.” [8] From myths that we create springs Eliade’s concept of hierophany [9]; the creation of sacred spaces. Alexei Lidov [10] further suggests that the creation of sacred spaces at first happens because of what he calls “heirotopy” the “creation of sacred spaces regarded as a special form of creativity,” Lidov’s idea is that the hand of man creates, influences and brings into existence a place where “Every sacred space implies a hierophany, an eruption of the sacred that results in detaching a territory from the surrounding cosmic milieu and making it qualitatively different”.

In the sphere of Black Rock City, the Temple delineates the profane or mundane from the sacred and that juxtaposition provides a framework for Burning Man to have a deeper significance than if it were just a weeklong festival in the desert.

With this in mind, I asked David Best if he thought that the Temple would have come into existence eventually if he and Jack Haye hadn’t built that first Temple. I’ve mentioned before that David Best can be quite a charming man, with blue piercing eyes that look into you when you’re speaking. He listens intently to people who come to him and there is an endless stream of people who want to talk with him. When I asked that question he told me a story.

With this in mind, I asked David Best if he thought that the Temple would have come into existence eventually if he and Jack Haye hadn’t built that first Temple. I’ve mentioned before that David Best can be quite a charming man, with blue piercing eyes that look into you when you’re speaking. He listens intently to people who come to him and there is an endless stream of people who want to talk with him. When I asked that question he told me a story.

“Do I think it would have come? Well gee, that’s a vanity question you’ve asked me.” He laughed and sarcastically replied, “Don’t know where I’ll go with that. Y’no, I’m the greatest guy in the world.” Then he continued,

“I went down and talked to [a large computer company] and they call their place a campus. They have a barber shop, you can get a haircut. There were three different restaurants, at their campus. I forget how many people are there, 2,000, 3,000 people. If you feed that information into a computer, for 2,000 people, at least three of them are going to have lost a family member. And they don’t have any place in their campus to address [that] and they want to profess that they’re building a family yet they don’t have a place to address the loss of a family member.”

“It’s like, when Burning Man built up that population, we all of the sudden needed that. It was just an obvious absence. There was a void that no one really noticed. They got the porta potties, they’ve got the police station, they’ve got the medical and they’ve got the Man. They just didn’t have a place for grief. And the Man kind of did grief for a while, but it was a mixture of so much celebration that it was hard to really have a quiet place.”

“So in all truthfulness, it would have happened sometime. The fact that I was lucky enough to do one is a lucky punch.”[11]

The Process of Building a Temple

There is a lot of empty space to fill up in Black Rock City.

People interested in building the Temple each year submit proposals to the Burning Man organization to basically do what Larry has said is one of the main purposes of Burning Man, “To blend life and art so you can’t tell the difference.”

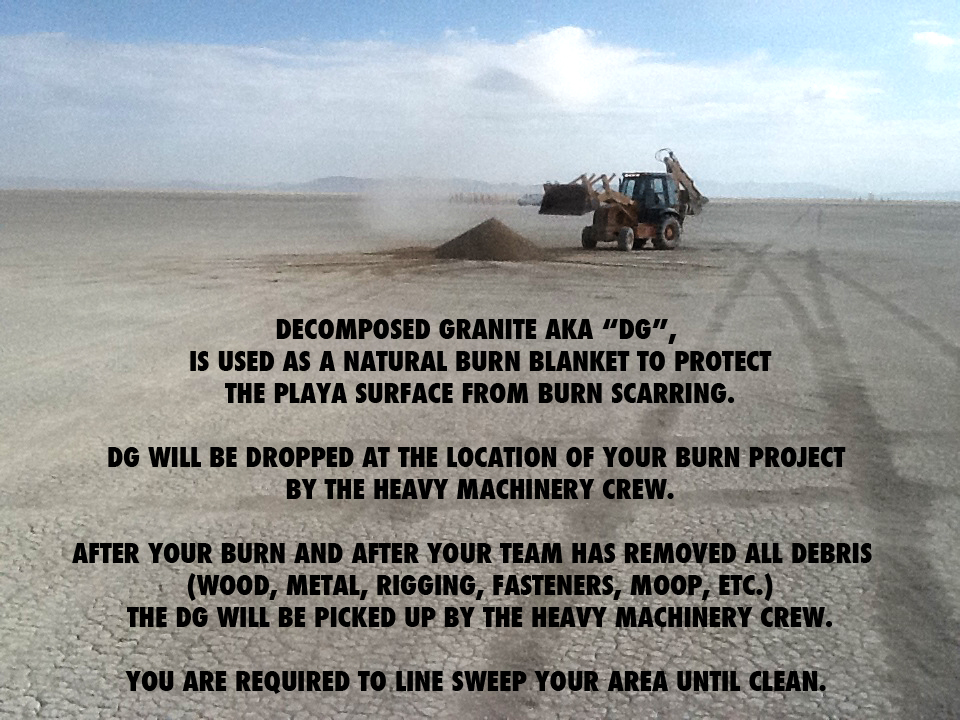

I spoke with a lot of people when I was researching what it took to build a Temple. Obviously, if you think you have the skills and resources to build a Temple at Burning Man, you’ve successfully built large scale art installations out there before and you’re well aware of the challenges you face. You understand how to keep a team productive and cohesive. You have tools and access to places to prebuild the Temple. You can build something that is safe, accessible, finished, and that won’t require last minute fixes just to get it standing and safe enough for Burning Man. You understand what “dust days” are and how to incorporate them into a project timeline. You have a group of people with mad sets of skills and a drive to try to pull off something as difficult as building something at Burning Man that everyone will notice and have an opinion on how you did.

I spoke with a lot of people when I was researching what it took to build a Temple. Obviously, if you think you have the skills and resources to build a Temple at Burning Man, you’ve successfully built large scale art installations out there before and you’re well aware of the challenges you face. You understand how to keep a team productive and cohesive. You have tools and access to places to prebuild the Temple. You can build something that is safe, accessible, finished, and that won’t require last minute fixes just to get it standing and safe enough for Burning Man. You understand what “dust days” are and how to incorporate them into a project timeline. You have a group of people with mad sets of skills and a drive to try to pull off something as difficult as building something at Burning Man that everyone will notice and have an opinion on how you did.

Every person I spoke with told me that a Temple build is something so important to the community that there’s a lot of pressure to get it done on time and to have it ready for when Black Rock City citizens begin arriving on Sunday. The Temple isn’t an art installation that can be in the process of going up throughout the week. It isn’t the kind of installation that can be bailed out on playa at the last minute. It is something that only those who have proven they can handle a large scale installation should even think about attempting.

Everyone has their own style of getting it done. The most important thing is that it gets done and I was fortunate enough to talk to some of the people who have done that.

Bill Codding who’s worked on several of David’s Temple told me their crew has a flat structure, with David running the show and all the volunteers taking direction from him. They have a head framer and people with skill sets in routing, carpentry and who can train the volunteers, but everyone has the ability to work on what they want to with David orchestrating everything. They have about 300 people on the Temple crew who have worked on various Temples over the years and Bill has a list of people he can call on, but getting volunteers isn’t an issue, as there are plenty of people who always want to work on the Temple.

Bill Codding who’s worked on several of David’s Temple told me their crew has a flat structure, with David running the show and all the volunteers taking direction from him. They have a head framer and people with skill sets in routing, carpentry and who can train the volunteers, but everyone has the ability to work on what they want to with David orchestrating everything. They have about 300 people on the Temple crew who have worked on various Temples over the years and Bill has a list of people he can call on, but getting volunteers isn’t an issue, as there are plenty of people who always want to work on the Temple.

At the work site in 2012, weeks before the Temple was opened, Chunk, aka Richard told me that about 1/3rd of their crew are skilled laborers and “There’s lots of on the job training and I’m working with David for the artistic and community experience. You don’t get that in everyday life. Seeing people enjoy it. The overall creation is a thing of beauty in the flames. It has a phoenix affect and is catharsis for so many people. We’re all contributing to Black Rock City’s Temple as a place of grieving. It’s a sacred space, not a disco.”[12]

I also spoke with Jess Hobbs who in 2010, along with Rebecca Anders and Peter Kimelman designed and headed up the building of the Temple of Flux. Their group had an existing infrastructure of people who had worked together on a bunch of projects and they came at it with all their combined knowledge. They put together a team that included structural engineers and experienced carpenters. They also included novices because a big part of their organization’s passion is having people learn new skills by building collaborative art. Jess stressed that a project as large as the Temple also needs to have an extensive Administration team to handle Finance, Fundraising and to organize resources and volunteers. They were able to successfully utilize the Burning Man social network and effectively advertise their fundraising efforts at mainstream publications like CNN and Fast Company.

I also spoke with Jess Hobbs who in 2010, along with Rebecca Anders and Peter Kimelman designed and headed up the building of the Temple of Flux. Their group had an existing infrastructure of people who had worked together on a bunch of projects and they came at it with all their combined knowledge. They put together a team that included structural engineers and experienced carpenters. They also included novices because a big part of their organization’s passion is having people learn new skills by building collaborative art. Jess stressed that a project as large as the Temple also needs to have an extensive Administration team to handle Finance, Fundraising and to organize resources and volunteers. They were able to successfully utilize the Burning Man social network and effectively advertise their fundraising efforts at mainstream publications like CNN and Fast Company.

Jess also mentioned that past Temple builders were helpful when they had questions, notably David Umlas and Marrilee Ratcliffe who had built Fire of Fires Temple the year before in 2009 and Tuk Tuk and Shrine who built 2008’s Basura Sagrada Temple. The Burning Man artist community is a dynamic one where collaboration and knowledge sharing is paramount and the sum total of Temple building knowledge is accessible for the most part.

Jess also mentioned that past Temple builders were helpful when they had questions, notably David Umlas and Marrilee Ratcliffe who had built Fire of Fires Temple the year before in 2009 and Tuk Tuk and Shrine who built 2008’s Basura Sagrada Temple. The Burning Man artist community is a dynamic one where collaboration and knowledge sharing is paramount and the sum total of Temple building knowledge is accessible for the most part.

I was talking with Jack Haye about how things developed with the first Temples. How did elements of the Temple come about? He was the original Construction co-ordinator and continues to consult with David when he is building the Temple. Jack explained how the original Temple was a project built by their camp. He talked about the organic spontaneity of things that became part of the Temple; the original dinosaur cutouts they discovered that were recycled to create the ornate decorations, the found wooden blocks on the property David and Jack had their studios on in Northern California, that became pieces of wood where people inscribed names of their loved ones to be burned. He told me how there was an evolution of elements such as the central structure (an altar, or with the Temple of Juno, the chandelier) being a remembrance to people who took their own lives.

I was talking with Jack Haye about how things developed with the first Temples. How did elements of the Temple come about? He was the original Construction co-ordinator and continues to consult with David when he is building the Temple. Jack explained how the original Temple was a project built by their camp. He talked about the organic spontaneity of things that became part of the Temple; the original dinosaur cutouts they discovered that were recycled to create the ornate decorations, the found wooden blocks on the property David and Jack had their studios on in Northern California, that became pieces of wood where people inscribed names of their loved ones to be burned. He told me how there was an evolution of elements such as the central structure (an altar, or with the Temple of Juno, the chandelier) being a remembrance to people who took their own lives.

Each time a new artist takes on the Temple, they re-imagine it, but bring elements of what has become a structural definition along with them. The Temple of Flux was probably one of the biggest departures from previous Temple designs and they intentionally refashioned the conventional idea of the Temple, but even then they created a space and in that space had “caves” for memorials. They also kept one of these caves as a remembrance place for suicides. Basura Sagrada, headed by Shrine and Tuk Tuk conceptualized the Temple as their “Sacred Trash” concept with the goal of making “something amazing and exotic out of materials deemed unworthy, the stuff we throw away every day. And while it is obvious that making something beautiful out of refuse is a political act, the question we hope to answer with this project is whether it can also be a spiritual act. We believe that it can.” [13] Mark Grieve built two Temples with the Temple Crew, 2005’s Temples of Dreams that utilized space in a village of shrines, pagodas and spires around a central Temple and the Temple of Hope in 2006 that featured a grand central stupah. In 2011, Chris “Kiwi” Hankins, Diarmaid “Irish” Horkan and Ian “Beave” Beaverstock and the International Arts Mega Crew (IAM) set out to build the largest Temple ever brought to the playa using “49,360 lineal feet of Sustainable Forestry Initiative certified lumber” [14] The Temple of Transition was massive, with five towers connected to the main tower by arching walkways.

Each time a new artist takes on the Temple, they re-imagine it, but bring elements of what has become a structural definition along with them. The Temple of Flux was probably one of the biggest departures from previous Temple designs and they intentionally refashioned the conventional idea of the Temple, but even then they created a space and in that space had “caves” for memorials. They also kept one of these caves as a remembrance place for suicides. Basura Sagrada, headed by Shrine and Tuk Tuk conceptualized the Temple as their “Sacred Trash” concept with the goal of making “something amazing and exotic out of materials deemed unworthy, the stuff we throw away every day. And while it is obvious that making something beautiful out of refuse is a political act, the question we hope to answer with this project is whether it can also be a spiritual act. We believe that it can.” [13] Mark Grieve built two Temples with the Temple Crew, 2005’s Temples of Dreams that utilized space in a village of shrines, pagodas and spires around a central Temple and the Temple of Hope in 2006 that featured a grand central stupah. In 2011, Chris “Kiwi” Hankins, Diarmaid “Irish” Horkan and Ian “Beave” Beaverstock and the International Arts Mega Crew (IAM) set out to build the largest Temple ever brought to the playa using “49,360 lineal feet of Sustainable Forestry Initiative certified lumber” [14] The Temple of Transition was massive, with five towers connected to the main tower by arching walkways.

Jess Hobbs put it really well when she told me “Burning Man is an experiment and the Temple should also be an experiment.”[15]

Volunteers and our Community

One thing unites all Temple builders. They are building something that is all inclusive and for all Black Rock City citizens. As such, certain design elements have been carried forward with each reinterpretation of the Temple including creating a space that is both intimate, with areas (often called altars) for folks to leave tributes, as well as creating a large enough gathering space capable of holding hundreds (possibly a thousand) at a time, so that it’s a true community area.

One thing unites all Temple builders. They are building something that is all inclusive and for all Black Rock City citizens. As such, certain design elements have been carried forward with each reinterpretation of the Temple including creating a space that is both intimate, with areas (often called altars) for folks to leave tributes, as well as creating a large enough gathering space capable of holding hundreds (possibly a thousand) at a time, so that it’s a true community area.

When I was hanging out with David Best’s Temple crew I noticed that, like most projects at Burning Man, the volunteers care deeply about the Temple, but there is an added dimension to this particular project. Many of them have lost someone close to them and the Temple has helped them to grieve and let go. Every person on the Temple Crew I met told me that when they heard David was building the Temple in 2012, they wanted to work with him. The process of building a Temple, for a majority of the Temple Crew, is cathartic in the same way the Burn of the Temple is and many of them feel they are contributing in remembrance of someone they’ve lost.

I asked Jess Hobbs about volunteers. The Flaming Lotus Girls, and now the Flux Foundation have a lot of members. How did they handle the influx of people who wanted to work with them? She said, “We had a lot of people come to us to work on the Temple. We took into consideration if they’d worked on Temples before and we tried to accommodate everyone” then she added that “The Temple attracts people who are grieving and in the process of letting go. We had some really heavy moments with people, especially the day before we burned it.”

Tuk Tuk talked about how so many people volunteer to make “The Temple part of their own. They wanted to touch a piece of it.”[16]

Tuk Tuk talked about how so many people volunteer to make “The Temple part of their own. They wanted to touch a piece of it.”[16]

The Temple Guardians are another volunteer phenomenon who appeared organically in 2002. Part of their purpose of “holding space” is “to protect the Temple and all of those who visit it” and they state “We do not make rules, nor are we enforcers; we watch quietly and act skillfully when necessary to protect the safety and sacred space of the Temple.” [17]

David Best handles his volunteers with such empathy it was something that helped me develop a deeper understanding of what the Temple is all about. Watching him interact with his crew by taking time no matter what was happening and to listen to them, console them and help them through whatever process of letting go they were going through, was pretty intense and demonstrated to me one of the reasons our community is something I care so deeply about. There are other memorial art installations that come to the playa year after year, but the Temple has become a focus of so much of that energy that not only is it moving to see it in action, it is important for people to realize just what kind of a burden they are taking on if they want to propose building a Temple. Volunteers will appear who have motives that are deeper than simply “getting the job done”.

David Best handles his volunteers with such empathy it was something that helped me develop a deeper understanding of what the Temple is all about. Watching him interact with his crew by taking time no matter what was happening and to listen to them, console them and help them through whatever process of letting go they were going through, was pretty intense and demonstrated to me one of the reasons our community is something I care so deeply about. There are other memorial art installations that come to the playa year after year, but the Temple has become a focus of so much of that energy that not only is it moving to see it in action, it is important for people to realize just what kind of a burden they are taking on if they want to propose building a Temple. Volunteers will appear who have motives that are deeper than simply “getting the job done”.

I talked with David Best about his volunteers and he told me the story of a woman who, while she had few skills that could be tapped to build a Temple, wanted passionately to work on it. David had been in a discussion about building the Temple with another artist who mentioned that they thought there would be no room for someone like this woman in his crew if he were to build the Temple.

David relayed that the woman had said,

“I can’t do anything, I have no skills, but I want to be on the Temple crew”and he continued,

“We were going, how we are going to deal with her? And she came up to the work weekend. I thought maybe we can just tire her out. Maybe she can just see for herself that she can’t do it. Well, she didn’t quit. She didn’t quit. And we finally went, she’s gotta be on the crew and she came up to me in line, we were at lunch one day working on the Temple, and she came up and said, “I want to thank you for letting me be on the crew” and I said we wouldn’t be worth a shit if we didn’t let you on the crew. We wouldn’t be a Temple crew if you couldn’t work with us.”

David told this to the other artist who said “Well you know you can’t have people who slow your project down.”

David replied, “You don’t build a temple for the finished product, you build it for the crew. It’s for those people who are building it. I could build a temple with 20 people in half the time. I’ve done it in half the time. But what it would lose is its soul and the heart. And that comes from P being in a wheelchair or T being unable to do that, or someone else who’s artistically challenged or someone who’s challenged using tools. It’s those layers of the commitment from those people.”

“We’re talking about other people coming to build it and I’m saying that in the screening process of someone saying hey I want to build the Temple; we kinda have to look for what the intention is. Is it to make a spectacular, the biggest burn you can possibly make? I mean that’s kinda cool, but there’s gotta be something else.”[18]

Someone sitting at the table with us said, “It has to spiritually resonate” and David agreed.

Intention

When we think about intention, we should return to the question artists who want to build a Temple should ask themselves, not “WHAT am I doing this for?” but rather “WHO am I doing this for?”

When we think about intention, we should return to the question artists who want to build a Temple should ask themselves, not “WHAT am I doing this for?” but rather “WHO am I doing this for?”

Jack Haye told me that their camp in 2000 and 2001 that created the original Temples was called Sultan’s Oasis, and their themecamp description was:

“The Sultan’s camp is to be a place where you can prostrate yourself before a greater entity and find transformation” and in 2001 it was “The sultan is back at his oasis, offering weary travelers a place to rest.”

Jack said their philosophy was one of service and that is something that needs to be impressed on people who attend Burning Man. Jack said that “in camp we would invite people in and say ‘How can we serve you’, not touchy feely, but ‘How can I help you?’ And the Temple is like that. It’s a shared community art piece. Some people want to build it to become rock stars but it’s really all about that service.”[19]

Jack said their philosophy was one of service and that is something that needs to be impressed on people who attend Burning Man. Jack said that “in camp we would invite people in and say ‘How can we serve you’, not touchy feely, but ‘How can I help you?’ And the Temple is like that. It’s a shared community art piece. Some people want to build it to become rock stars but it’s really all about that service.”[19]

Jack doesn’t see the Temple as a resume builder. It belongs to Black Rock City. It is a work of art, but it doesn’t exist as a piece of art unto itself. There are plenty of pieces each year on the playa that exist for themselves, as beautiful sculptures. The Temple is different.

Jack said, “It’s not there to call attention to itself, it is there as a sacred, spiritual space.”

Sealed Up, Never to Return

Personally I was ambivalent about the Temple until this year. One year in the mid aughts, I put a picture of my grandparents in there with a goodbye and good luck inscription to them. Another year I made a little shrine to my dog of 16 years who I had to put down, but this year, after hanging out with so many people and hearing their stories of loss and letting go of that loss, of forgiving themselves and of taking part in building the Temple or of leaving totems to their loved ones that, as David Best has said, “everything is sealed up, never to return”[20] I came to an awareness that the Temple once complete and filled with remembrance is something consecrated and very significant to our community.

Personally I was ambivalent about the Temple until this year. One year in the mid aughts, I put a picture of my grandparents in there with a goodbye and good luck inscription to them. Another year I made a little shrine to my dog of 16 years who I had to put down, but this year, after hanging out with so many people and hearing their stories of loss and letting go of that loss, of forgiving themselves and of taking part in building the Temple or of leaving totems to their loved ones that, as David Best has said, “everything is sealed up, never to return”[20] I came to an awareness that the Temple once complete and filled with remembrance is something consecrated and very significant to our community.

On Sunday night I walked out to the Temple burn and hung out, unexpectedly, in the Temple Bus with two new friends, one who was celebrating her mother who’d died 19 years ago. My friend had been allowed to get on a boom lift to place her mother’s ashes in the spire towards the top and her mom was next to a cat which delighted my friend. She said. “We celebrate the dead, but life is for the living. She’s been with me for 19 years, and she’s next to a cat. She always loved cats.”

Bagpipes played. Diva Marisa and Reverend Billy’s choir sang “Ave Maria”, and the three of us took swigs of Jameson befitting an Irish wake as the full moon inched towards the Temple. Once the Temple was lit by wandering purposeful shadow shapes in the courtyard carrying fire, we watched the roaring orange and red flames grow then engulf that structure until it became a delicate black skeletal outline against the glowing blazing inferno. I hugged my friend and saw the flames in her eyes as she looked on smiling, and said, “Mom has the east, the best view on the playa. Her and the cat.”

Bagpipes played. Diva Marisa and Reverend Billy’s choir sang “Ave Maria”, and the three of us took swigs of Jameson befitting an Irish wake as the full moon inched towards the Temple. Once the Temple was lit by wandering purposeful shadow shapes in the courtyard carrying fire, we watched the roaring orange and red flames grow then engulf that structure until it became a delicate black skeletal outline against the glowing blazing inferno. I hugged my friend and saw the flames in her eyes as she looked on smiling, and said, “Mom has the east, the best view on the playa. Her and the cat.”

When the spire outline grew thin, it finally leaned over slowly, and then collapsed upon the rest of the Temple sending a great chimney of embers floating upwards. My friend said, “Mother is free and so am I now. I really feel her. She would have liked this.”

I have no doubt she did, indeed, like it.[21]

Conclusion

I have attempted here to discuss the cosmological importance of the Temple as it appears in Black Rock City and to impress that it is a vital part of our shared Burning Man experience. The Temple is not just an art installation, but it encompasses a large range of serious spiritual requisites that add dimension to our community. Building a Temple in Black Rock City requires not only artistic and craft skillsets, and is something that is taken very seriously by our community, but along with it comes a set of volunteers who want to be part of it, to build and to protect it. As such, the Temple is something special and is, in one way or another, shared by all of us.

As with all Honorarium projects, each year’s Temple crew is expected to create something extraordinary, on time and within budget, but building a Temple also involves a substantial responsibility to not only the citizens of Black Rock City and the Burning Man community in general, but to the volunteers who will want to take part in the building of the Temple. It is something bigger than any artist who conceives and pulls it off because it is something that helps to define who we are as a community. It is about creating a shared space for everyone to take a part in, as Sarah Pike notes the Temple is “Burning Man’s largest collective piece of art.”[22]

As with all Honorarium projects, each year’s Temple crew is expected to create something extraordinary, on time and within budget, but building a Temple also involves a substantial responsibility to not only the citizens of Black Rock City and the Burning Man community in general, but to the volunteers who will want to take part in the building of the Temple. It is something bigger than any artist who conceives and pulls it off because it is something that helps to define who we are as a community. It is about creating a shared space for everyone to take a part in, as Sarah Pike notes the Temple is “Burning Man’s largest collective piece of art.”[22]

When they were building the Basura Sagrada Temple, Shrine said, “You are putting in what you want to let go, or putting in how you want to change your life. It’s what makes a sacred space.”[23]

In 2012 David designed thresholds to keep out bicycles and the distracting sound from art cars. Upon venturing out there, I felt like I was stepping across that threshold into another reality. The atmosphere was heavy with reflection and quiet chanting, prayers, the drawn out grrr of a digeridoo and other reverent sounds. I was overwhelmed with all the notes and altars, inscriptions, photos and totems that covered every square inch of the walls staring back at me. That most intimate space swells with so much grief and remembrance, so much reflection and meditation it is indeed what David Best has called an “emotional nexus”. The Temple provides a space for that essential urge, but unlike religion, that feeling is coming directly from our core, unadulterated by dogma.

In 2012 David designed thresholds to keep out bicycles and the distracting sound from art cars. Upon venturing out there, I felt like I was stepping across that threshold into another reality. The atmosphere was heavy with reflection and quiet chanting, prayers, the drawn out grrr of a digeridoo and other reverent sounds. I was overwhelmed with all the notes and altars, inscriptions, photos and totems that covered every square inch of the walls staring back at me. That most intimate space swells with so much grief and remembrance, so much reflection and meditation it is indeed what David Best has called an “emotional nexus”. The Temple provides a space for that essential urge, but unlike religion, that feeling is coming directly from our core, unadulterated by dogma.

Creating this place carries with it a heavy responsibility and should not be taken lightly.

Whoever is building the Temple each year brings it to our city as a gift for everyone. A friend of mine said “It’s a profound space. If people can’t confront it, they want to escape.” If you have been fortunate enough to not have experienced something that rocked your reality, you may have no use for the Temple. But if you ever need it, someone will be building it for you each year in Black Rock City.

Whoever is building the Temple each year brings it to our city as a gift for everyone. A friend of mine said “It’s a profound space. If people can’t confront it, they want to escape.” If you have been fortunate enough to not have experienced something that rocked your reality, you may have no use for the Temple. But if you ever need it, someone will be building it for you each year in Black Rock City.

Jess Hobbs told me, “We wanted to bring back the silence of the Burn. It was a gift and the Temple was the biggest thing we’d ever burned. It was a gift we gave to the community, but the biggest gift we ever got was what the community gave back to us.”

I’ve been to many Temple Burns over the years, but this year as I was trying to understand on a deeper level what it all meant, I felt that I’d come closer to realizing what a gift all our Temple artists, volunteers and playa citizens create each year. It is all about affirmation, closure, forgiveness and healing. On Sunday of the event this year I tried to describe how it feels to be there as a Temple burns and wrote the following that is not concerned with the how and why, the philosophy and meaning.

It just is.

“Tonight the Temple burns and all of the emotion we’ve put in there this week will wash up in a cathartic column of fire, sparks and ash that will send those notes of love and loss and of grief and forgiveness swirling into the night sky. Dust tornadoes will form and dance around us as if they are our loved ones lost, caressing us in the firelight’s glow, saying do not worry, everything is as perennial as the seasons, or the plants that return each spring or the love that brings us all together eventually.”

“Tonight the Temple burns and all of the emotion we’ve put in there this week will wash up in a cathartic column of fire, sparks and ash that will send those notes of love and loss and of grief and forgiveness swirling into the night sky. Dust tornadoes will form and dance around us as if they are our loved ones lost, caressing us in the firelight’s glow, saying do not worry, everything is as perennial as the seasons, or the plants that return each spring or the love that brings us all together eventually.”

Huge Thanks to everyone who contributed to this article by letting me interview them and thanks to Portaplaya, aka Todd Gardnier who took many photographs this year of the Temple and those who build it.

Also, there is an accompanying blog post where you can record your comments to others’ comments about your thoughts on this article.

[1] Lori Van Meter. “The Temples at Burning Man”, 2007 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/ptb/mso/dd/dd5/VanMeter%20paper.pdf p. 3.

[2] Moze, Initiations and Salutations. Burning Man Blog. http://blog.burningman.org/2011/07/culture-art-music/initiations-and-salutations/ 2011.

[3] Lee Gilmore, Theater In A Crowded Fire (University of California Press 2010)

[4] Lee Gilmore, The Temple: Sacred Heart of Black Rock City. Burning Man Blog. http://blog.burningman.org/2010/05/spirituality/the-temples/ 2010

[5] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (English Translation, Harcourt, Inc. 1957)

[6] Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy (Oxford Univ. Press 1923)

[7] Arnold Van Gennep, The Rites of Passage (Univ. of Chicago Press 1960)

[8] Larry Harvey, Viva Las Vegas, Speech at Cooper Union, New York City, https://burningman.org/culture/philosophical-center/founders-voices/larry-harveys-writings/viva/ 2002.

[9] Op. cit. Mircea Eliade, p. 26

[10] Alexei Lidov, Hierotopy. The Creation of Sacred Spaces as a Form of Creativity and Subject of Cultural History http://www.imk.msu.ru/Publications/lidov/01-Lidov-eng.pdf (Progress-tradition, Moscow) 2006, p 33-58.

[11] Moze, Interview with David Best, (Black Rock City 2012)

[12] Moze, A Sacred Place amidst the Dust http://blog.burningman.org/2012/09/building-brc/a-sacred-place-amidst-the-dust/ 2012

[13] Basura Sagrada: The 2008 Burning Man Temple, http://playajoy.org/?p=108 (2008)

[14] Temple of Transition – The tallest temporary wooden structure in the world. http://www.greendiary.com/temple-transition-tallest-temporary-wooden-structure-world.html (2011)

[15] Moze, Interview with Jessica Hobbs, 2012

[16] Basura Sagrada, http://current.com/shows/max-and-jason-still-up/89322038_basura-sagrada.htm (Current TV 2007)

[17] About the Temple Guardians, http://templeguardians.org/about-the-temples/

[18] Moze, Interview with David Best, (Black Rock City 2012)

[19] Moze,Interview with Jack Haye (2012)

[20] The Last Temple, Interview with David Best http://current.com/groups/art-and-style/87265491_the-last-temple.htm (Current TV 2007)

[21] Op. cit. Moze, A Sacred Place amidst the Dust

[22] Sarah M. Pike, Burning Down the Temple: Religion and Irony in Black Rock City(rd Magazine) http://www.religiondispatches.org/archive/culture/5082/burning_down_the_temple%3A_religion_and_irony_in_black_rock_city/ (2011)

[23] Basura Sagrada, http://current.com/shows/max-and-jason-still-up/89322038_basura-sagrada.htm (Current TV 2007)

If you are interested in learning more about how you can build the Temple in Black Rock City, visit BRC Temple Grants.