Petaluma artist David Best is well known for his sculpture, prints and art cars. Burning Man has inspired David to create huge, collaboratively built interactive temples which function as large-scale votive shrines. David is a master of recycling, using leftover wooden cutouts from the manufacture of children’s dinosaur kits as the raw material for fanciful multi-storied temples with pagodas, hanging lanterns, arched bridges, onion domes and altars. Participants visit the temple daily, leaving behind inscriptions to departed friends and family, photographs, letters, and mementoes. The mood is somber and contemplative; many weep, meditate, and embrace. The temples have been a cherished part of Burning Man since 2001, and their ritual burns on the last night of the event hold great significance for the community. David and his volunteer crew work tirelessly for months to complete the temples, and they are burnt to the ground without any thought of exhibits or sales.

Petaluma artist David Best is well known for his sculpture, prints and art cars. Burning Man has inspired David to create huge, collaboratively built interactive temples which function as large-scale votive shrines. David is a master of recycling, using leftover wooden cutouts from the manufacture of children’s dinosaur kits as the raw material for fanciful multi-storied temples with pagodas, hanging lanterns, arched bridges, onion domes and altars. Participants visit the temple daily, leaving behind inscriptions to departed friends and family, photographs, letters, and mementoes. The mood is somber and contemplative; many weep, meditate, and embrace. The temples have been a cherished part of Burning Man since 2001, and their ritual burns on the last night of the event hold great significance for the community. David and his volunteer crew work tirelessly for months to complete the temples, and they are burnt to the ground without any thought of exhibits or sales.

Berkeley sculptor Michael Christian has created elaborate metal sculptures for the event since 1997, most of which are experienced by participants who clamber around and up through them. He believes, “People don’t travel great distances to an incredibly hostile environment to impress people with their abilities as ‘artists’. They do it because they want and need to, and to enjoy the freedom of expression while it is available.”

Berkeley sculptor Michael Christian has created elaborate metal sculptures for the event since 1997, most of which are experienced by participants who clamber around and up through them. He believes, “People don’t travel great distances to an incredibly hostile environment to impress people with their abilities as ‘artists’. They do it because they want and need to, and to enjoy the freedom of expression while it is available.”

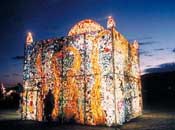

Dunsmuir, California artist Finley Fryer makes sculpture and buildings out of recycled plastic detritus collected by his local community. His Plastic Chapel was erected twice on the playa, where it served as a popular wedding site. San Francisco sculptor Dana Albany uses recycled materials, including animal bones and discarded books, in her large-scale installations like the Bone Tree and the Body of Knowledge.

Dunsmuir, California artist Finley Fryer makes sculpture and buildings out of recycled plastic detritus collected by his local community. His Plastic Chapel was erected twice on the playa, where it served as a popular wedding site. San Francisco sculptor Dana Albany uses recycled materials, including animal bones and discarded books, in her large-scale installations like the Bone Tree and the Body of Knowledge.

Baltimore artist Tim Kaulen fabricated an enormous inflatable woman from billboard vinyl cigarette ads; he drove her to the playa in the trunk of his car and inflated her with a household fan. Painter JennyBird Alcantara creates bizarre, psychological feminine images; in 2005 her paintings formed the entrance to the Funhouse, on which stood the Man.

A recent trend is the creation of large installations by community groups, only some of whose members are working artists. In 2005 Seattle’s Stronghold Productions created the Machine, a 60′ tall mechanical wood and steel temple, whose four arms were gradually raised by participants during the week of the event. As they turned three drive wheels, its transmission engaged gears that rotated its central core and upper platform, and spun and raised the limbs. Stronghold Productions is comprised of artists, designers, engineers, builders and fabricators, as well as arts administrators, writers, teachers, photographers, videographers, sound designers, and technologists.

A recent trend is the creation of large installations by community groups, only some of whose members are working artists. In 2005 Seattle’s Stronghold Productions created the Machine, a 60′ tall mechanical wood and steel temple, whose four arms were gradually raised by participants during the week of the event. As they turned three drive wheels, its transmission engaged gears that rotated its central core and upper platform, and spun and raised the limbs. Stronghold Productions is comprised of artists, designers, engineers, builders and fabricators, as well as arts administrators, writers, teachers, photographers, videographers, sound designers, and technologists.

An enormous mobile flower appeared on the playa that same year, built over an articulated man-lift by two groups from Los Angeles, Abundant Sugar and the DoLab. Many of the group members work in the film industry. San Francisco’s Flaming Lotus Girls create large-scale interactive fire art, such as the Angel of the Apocalypse, a 30′ long reclining bird with a driftwood body surrounded by sixteen curving vertical wings made of stainless steel piped with propane. Their group is radically inclusive; anyone who wants to join may do so, and will be taught to weld and to work with metal by the professional artists in the group.

Burning Man has spawned a new genre of art, and whether we consider it “insider” or “outsider” art hardly seems important. Some of it is made by untrained artists, and all of it lives outside of the conventional art world. At Burning Man, art-making is inclusive and does not require degrees or the approval of critics. In one sense this genre is not new at all, but harkens back to a time when there was no separation between art and life. The remaining question, perhaps, is one of quality: is all of this democratically produced art “good”? Clearly, some of the art is very accomplished and would stand up well to art world scrutiny; some is less so. In a community where the art is not intended to be sold or reviewed, but to generate community and interactivity, its aesthetic merit seems somewhat beside the point. In Black Rock City art is not a precious commodity to be marketed, dissected by critics, or locked up in a museum. It is a vital part of the community, whose shared experiences in its creation and its life on the playa give it meaning and value.

Burning Man has spawned a new genre of art, and whether we consider it “insider” or “outsider” art hardly seems important. Some of it is made by untrained artists, and all of it lives outside of the conventional art world. At Burning Man, art-making is inclusive and does not require degrees or the approval of critics. In one sense this genre is not new at all, but harkens back to a time when there was no separation between art and life. The remaining question, perhaps, is one of quality: is all of this democratically produced art “good”? Clearly, some of the art is very accomplished and would stand up well to art world scrutiny; some is less so. In a community where the art is not intended to be sold or reviewed, but to generate community and interactivity, its aesthetic merit seems somewhat beside the point. In Black Rock City art is not a precious commodity to be marketed, dissected by critics, or locked up in a museum. It is a vital part of the community, whose shared experiences in its creation and its life on the playa give it meaning and value.