I have some slides I’d like to show you now. These are just a few particular works, some of which I’ve been involved in.

Can you start the first slide?

This was done by an artist by the name of Jim Mason. We helped him with this, helped him finance it. We give out grants every year, a few, and they’re always either for art that is part of our yearly theme, or art that appears in prominent public places. We do a theme because it encourages artists to collaborate and cooperate, and because it gives our participants something to share. And our first tenet, what we nearly always require, is that it be interactive.

This was done by an artist by the name of Jim Mason. We helped him with this, helped him finance it. We give out grants every year, a few, and they’re always either for art that is part of our yearly theme, or art that appears in prominent public places. We do a theme because it encourages artists to collaborate and cooperate, and because it gives our participants something to share. And our first tenet, what we nearly always require, is that it be interactive.

You will see two upright poles in the back of this view. They actually had ice on them and formed four ice obelisks. The diagonal pipe that goes through the ice ball itself also had a function. It helped form a giant sundial. Now, Jim made this ice ball out of — I don’t know how many — tons of ice in the middle of a barren plain hundreds of miles from the nearest power grid, and it is filled with clocks. This piece is about the processes of geologic time, and it melted, finally, over the course of several days. It was sort of a high concept work, very expressive, and something that would probably be a big hit here at this museum if you put it in the courtyard. It was a brilliantly conceived work.

But the interesting thing, for me, about this piece is that people interacted with it throughout the event. It being Burning Man, of course, people didn’t worry about permission. They were rubbing up against it with their naked bodies the entire time. There was also a project to make snow cones out of it with ice scrapers, so you could eat the art.

Now, I was just in the exhibit upstairs, and they have this, I don’t know what it was, but it’s an installation with a monitor and a carpet stretched out on the ground, and, for a moment, I forgot myself. I thought I was at Burning Man, and so I stepped on the carpet. It was a very modest interaction. I put two inches of the sole of my shoe on it, and, of course, the guard was there in an instant. Because, you know, museums in our day are sort of a cross between a laboratory and a church, and have the least attractive qualities of both. But, I won’t bite the hand that feeds me, so we’ll pass on. [applause, laughter]

Let’s see the next slide.

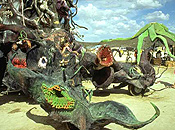

I included this slide because I don’t know who did this piece. It’s 15 feet tall. It is an art weed. I mean, I’d like to know who the artist is. Anyone who knows, I wish they’d tell me. But, this is typical of our experience out there. For all I know, it grew out the ground. An artist just did this. He or she wasn’t after us to get credited, and they didn’t put their name next to it. It was a gift to the community, and a beautiful one, too.

I included this slide because I don’t know who did this piece. It’s 15 feet tall. It is an art weed. I mean, I’d like to know who the artist is. Anyone who knows, I wish they’d tell me. But, this is typical of our experience out there. For all I know, it grew out the ground. An artist just did this. He or she wasn’t after us to get credited, and they didn’t put their name next to it. It was a gift to the community, and a beautiful one, too.

Let’s see the next one.

This is the One Tree. This is public art. You can see people interacting with it. It generated society around itself. It put people in a relationship to one another. It dripped water through those branches and people bathed in it. It also generated steam, and, if we look at the next slide, you’ll see it sprouted leaves of flame. This was by Dan Das Man, a brilliant artist, and if you come to the event I’m sure you’ll see more work by him.

This is the One Tree. This is public art. You can see people interacting with it. It generated society around itself. It put people in a relationship to one another. It dripped water through those branches and people bathed in it. It also generated steam, and, if we look at the next slide, you’ll see it sprouted leaves of flame. This was by Dan Das Man, a brilliant artist, and if you come to the event I’m sure you’ll see more work by him.

The next slide, please…

This is my baby. Now, we called this the Nebulous Entity because I didn’t want people to know what the hell it was. We were very insistent on ambiguity. The Burning Man’s famous for our never having attributed meaning to him, and that’s done on purpose. He is a blank. His face is literally a blank shoji-like screen, and the idea, of course, is that you have to project your own meaning onto him. You’re responsible for the spectacle.

This is my baby. Now, we called this the Nebulous Entity because I didn’t want people to know what the hell it was. We were very insistent on ambiguity. The Burning Man’s famous for our never having attributed meaning to him, and that’s done on purpose. He is a blank. His face is literally a blank shoji-like screen, and the idea, of course, is that you have to project your own meaning onto him. You’re responsible for the spectacle.

So this was the nebulous entity, and we made it as nebulous as you can imagine. A brilliant artist, Michael Christian, created the sculpture, and Dr. Aaron Wolf Baum designed a system that absorbed ambient sounds from the environment, fractalized them, and then broadcast them back to people. It continuously talked to people in a sort of burbling dialect. You’ll notice also that it is mounted on airplane wheels. When we were designing it, one of the artists said, “Let’s put a motor in it!” This being America, someone was bound to say that. [laughter] I said, “No. No, this has got to require people’s effort. They should expend some calories to make it move! They need to invest themselves in its motion!”.

You know, if you take people and scatter them like grains of sugar, or imagine them as ants on a sidewalk in a perfectly blank featureless environment, you’ll find that they’ll spontaneously begin to create certain kinds of order. It is in our nature. The first thing they’ll do is surround any focal point of activity. They’ll form circles. You will see this happen naturally. They never form a square, — I’ve never seen a rectangle — always a circle. Then, if you take that focal point and move it, you’ll create a vector, and that forms a parade, a procession.

You know, if you take people and scatter them like grains of sugar, or imagine them as ants on a sidewalk in a perfectly blank featureless environment, you’ll find that they’ll spontaneously begin to create certain kinds of order. It is in our nature. The first thing they’ll do is surround any focal point of activity. They’ll form circles. You will see this happen naturally. They never form a square, — I’ve never seen a rectangle — always a circle. Then, if you take that focal point and move it, you’ll create a vector, and that forms a parade, a procession.

So the idea in this flat environment was to take advantage of the flat plain and make a work of art that only people could move, a giant plaything, and then permit it to move about, as if animated by its own impulse, and it generated parades and processions throughout the city.

Here, at its base, you see speaking tubes. People could talk into those apertures and it would distort their voice. We painted it white, so it would be reflective, and we didn’t move it during daytime, only at night.

This was meant to maximize the mystery. It had a light source which created this molten flow that moved and shimmered up and down, and made its tentacles appear to writhe. And the idea was that this great corporate organism absorbed information. It was like a living version of the internet. It was a nebulous entity, and it roved, and it came into contact with everybody. I was trying to design the most interactive piece of large-scale sculpture I could imagine.

This was meant to maximize the mystery. It had a light source which created this molten flow that moved and shimmered up and down, and made its tentacles appear to writhe. And the idea was that this great corporate organism absorbed information. It was like a living version of the internet. It was a nebulous entity, and it roved, and it came into contact with everybody. I was trying to design the most interactive piece of large-scale sculpture I could imagine.