A conversation with Larry Harvey by Darryl Van Rhey (1997)

Darryl Van Rhey: The system that has supported Art in America appears to have reached a crisis; patronage is disappearing, galleries are closing, even the NEA is under siege. Yet Burning Man has grown into a large-scale venue for new art. Why is this?

Larry Harvey: Well, I think you’re right. The folks upstream have raised their dams. The old patronage system, like so many other hierarchies in American life, is breaking down. Artists are perennial have-nots. I don’t think they can expect much in the future, but this may be a blessing in disguise.

DVR: Why?

LH: Because the old system doesn’t work. Artists are trapped. Very little money goes directly to creators. Most grant funding goes to institutions. From there it trickles down in little dribs and drabs. This has the effect of isolating artists. For one thing, it isolates them from their audience. It’s one thing to delight ordinary people with your work, quite another to “delight” a board of directors. Committees aren’t creative and bureaucracies haven’t a delightful bone in their bodies. Institutions, supposedly designed to disseminate art, often become the real clients. There are political tests, peer reviews, and the ever-present lust for institutional prestige. I’m not saying some deserving work doesn’t get funded, but grants and gallery berths are always in short supply. And this, in turn, leads to a second form of isolation. Artists are competing for scarce resources and this isolates them from one another. Everyone is desperate for individual distinction — “Choose me! Choose me!’. It creates a kind of mania. All over the South of Market district in San Francisco artists are waking up at 3 AM, covered with flop sweat, thinking, “Oh my God! What if I’m derivative?”. This is not a creative climate. Collaboration is the soul of culture, but the system divides people.

DVR: What is the alternative?

LH: Populism; an art that is immediately available to large numbers of people. Nothing’s going to trickle down. It’s time for artists to spread out. We need a broader public.

DVR: What are the characteristics of populist art?

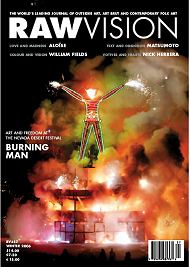

LH: It is immediate and involving. It’s collaborative and it breaks down barriers between audience and art work. It’s based upon participation — it’s radically interactive — and it contemplates the facts of life. I’ll give you an example. Last year Ray Cerino created a public shower for us in the desert. He called it “Water Woman”. A stream of water spouted from between its legs. The piece itself was very elegant, but, beyond any question of form, it required an action. It was grounded in need. It was based on survival. People got naked — it was fun and it was funny. Another example is Pepe Ozan. Pepe’s based in San Francisco and he leads a troupe of sculptors. During three successive years they have created large-scale towers — hollow columns, chimneys, really — which they craft from rebar, metal mesh and mud. Last year’s lingam, as it’s called, was three stories tall. Pepe’s work is quite sensuous, very tactile, plastic, elaborately formed. Under any circumstances this would constitute a significant achievement. But to stop at the completed product is to miss the point. On Saturday night they filled the tower with firewood. It glowed like molten magma, spouted fireworks, and an elaborate operatic performance ensued. Moreover, more than five thousand people, many of them costumed or painted with mud, gathered around it to celebrate. The point I’m making is this: populist art, the kind of art we’re creating, convenes society around itself. This goes far beyond the concept of an exhibition. We see thousands of people who normally wouldn’t go near a gallery. And this is true for artists also. We give them a community in which to meet and work collaboratively with hundreds of other creators, and with a freedom and at a scale that they can find in no other place.

DVR: What can you tell me about the content of the art your project has generated?

LH: We dictate nothing to the individual creator. However, every year we create a theme. Last year our motif was Hell; the premise being that a supra-national conglomerate called “HELCO” was attempting to purchase the Project. It did a very brisk business in souls. We actually created a uniformed sales force that recruited customers. A sculptor, Al Honig, created a sucking device which extracted and processed people’s souls, and we transferred this theme to the desert in the form of a huge walk-through installation that was spread out over a quarter mile. This included a four story complex — HELCO’s world headquarters — which we eventually burned to the ground. HELCO sank into insolvency.

DVR: So the work was satirical?

LH: Satirical and satanic; the best of both worlds. This year we will satirize the New Age. We plan to stage earth and fertility rites. My favorite so far is Cruel Mistress Gaia — Mother Earth meets Venus in leather. She’ll be served by a court of very subservient vegetables. It will be funny, unnerving and weird, but, as with any good joke, we also have a very serious intention. We use our shows to create collective stories, myths which dramatize the life of our community. This year we’ll be moving to a new site; land on the edge of a smaller playa. We’re founding a new home, so some serious earth magic seems in order.

DVR: Can you elaborate on this concept of art as myth?

LH: Sure. It’s part of giving art a greater social function. Quite obviously though, since we’re not members of a pre-literate culture, we’ve had to look beyond received oral traditions for material. Our technique is to appropriate elements of mass culture, symbols that pervade popular consciousness. Our myths have a post-modern twist. It is a kind of guerrilla strategy. Pop culture and the media tend to parasitize authentic culture, transforming grass-roots art into commodities. We’ve simply reversed this process. We turn pop culture back into myth that expresses the life of an actual community. We appropriate the appropriators. It’s a survival tactic for the Nineties.

DVR: We’ve been talking about the survival of culture, but how does Burning Man promote the survival of individual artists?

LH: Throughout it’s entire history the Project has operated outside the system. We’ve struggled unfunded. We have learned to survive. What we’ve created is a forum where creators can connect and learn from our example and from one another. For one thing, we attract a huge public, thousands of participants. Remotely, through the media, this includes millions of people. We’ve been on CNN and we’ve been featured in the New York Times Magazine, the Village Voice — perhaps a hundred other periodicals. At our Web-site we’ve connected to 1,500 people a day and we’re organizing a gallery on the Internet that will feature individual artists. I think this offers a way out, a way to escape the art ghetto — what Tom Wolfe called “Cultureburg”; a smallish self-regarding town of galleries, patrons, and art administrators. I believe that what we’re doing is a model for the future; that it will spread by example and create new venues, a new kind of environment for work that includes a much larger public. The reason for our exponential growth is that we offer people something that they can find nowhere else. We’re reclaiming the social function of art and that’s a very powerful attractant. I want artists to come out and absorb the ethos and the style we’ve invented. After all, what have they really got to lose?

Larry Harvey is the founder and director of the Burning Man Project. Darryl Van Rhey is a journalist and long time observer of Burning Man.

Mission

Mission