1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

— Isaac Asimov, I, Robot

I, Robot, first published in 1950, is a collection of short science fiction stories by author Isaac Asimov. It is perhaps most famous for the three essential laws embedded deep in every robot’s positronic brain.

At first glance, these ethical precepts seem simple enough; they are really not much different from the Golden Rule. But a team of robot psychologists, engaged in what we would today call quality control, soon discover certain glitches that become quite sinister.

Asimov, like philosophers before him, naturally assumed that there could be no true morality without emotion. This battle between the qualitative and the quantitative, between human consciousness and abstract calculation, isn’t easily resolved, but one thing does seem certain: nobody likes an angry robot.

This year’s art theme will focus on the many forms of artificial intelligence that permeate our lives; from the humble algorithm and its subroutines that sift us, sort us and surveil us, to automated forms of labor that supplant us. Are we entering a Golden Age that frees us all from mindless labor? Everything, it seems, depends on HMI, the Human-Machine Interface. In a world increasingly controlled by smart machines, who will be master and who will be the slave?

“People degrade themselves in order to make machines seem smart all the time. Before the crash, bankers believed in supposedly intelligent algorithms that could calculate credit risks before making bad loans. We ask teachers to teach to standardized tests so a student will look good to an algorithm. We have repeatedly demonstrated our species’ bottomless ability to lower our standards to make information technology look good.”

― Jaron Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget

It is no wonder that AI is starting to look all-powerful and inevitable. So-called creative content is increasingly hackwork; indistinguishable from the output of algorithms programmed to imitate prose, poetry, and pop songs. It’s not so much that robots are getting closer to human as that we are lowering our standards of comparison. Such compromises make us dumber and lazier — putting our trust in algorithms without questioning their assumptions.

And yet, if we turn the telescope around and regard the capacity of robots to process information and draw conclusions from almost unlimited databases, it becomes possible to imagine a solipsistic world in which most of our friends or even all of our friends will be robots: we would be surrounded by a slave labor force. Having out-sourced our minds, we might choose to out-source our selves. Who doesn’t want a friend who mirrors one’s own opinion of one’s self? Already it appears we may be moving in this direction. Consumerism makes us crave convenience and seek instant gratification, pointing toward an automated future shorn of human contact.

“More human than human is our motto.”

― Dr. Tyrell, Blade Runner

The allure of immortality and god-like powers is as old as god. The Greeks, who more or less invented humanism, had a word for this ― they called it hubris, making it the basis of all tragedy. This enduring fantasy is lately clothed in cyber-togs. It is said that computational power is increasing exponentially, much like the singularity that created the universe, and charts and numbers are employed to predict the point in time at which this supra-intelligence will take over.

This is a millenarian idea, sometimes called the Rapture of the Techies, and like all such schemes, it is essentially a religious concept now dressed in the trappings of science. In this scenario, the future rule of one vast integrated Robot will exceed all human comprehension. This notion also contains an ingenious escape clause, a sort of intellectual insurance policy. When pressed to pinpoint exactly when this event will occur, its acolytes reply that it may have already happened — its advent will elude the grasp of slimy brains. This is a contest between wet intelligence, something that we barely understand that has evolved on earth over a span of billions of years, and dry intelligence, which in its digital form was invented in 1936.

“Smart machines may make higher GDP possible, but they will also reduce the demand for people — including smart people. So we could be looking at a society that grows ever richer, but in which all the gains in wealth accrue to whoever owns the robots.”

― Paul Krugman

Burning Man has been pioneering the post-work world for decades. What would you do if you could do what you wanted? And not what you had to do to make a living? Reawakening those desires is a transformative experience; relearning how to dream, how to play, how to have desires that arise innately from your being, rather than selected off a shelf of preprogramed experiences — and perhaps most importantly, to do all this in a community that brings you into living contact with your fellow human beings.

Wizard of Oz: “As for you, my galvanized friend, you want a heart. You don’t know how lucky you are not to have one. Hearts will never be practical until they can be made unbreakable.”

Tin Woodsman: “But I still want one.”

This year we invite participants to use their native genius to create expressive robots of all kinds. We also welcome art that examines how it feels to live in a world that is filled with robots that watch us, track us, hack us, read our tweets and emails, listen to our phone calls, and sell this information to other robots. This is a science fiction theme. As always, any work of art by anyone, regardless of our theme, is welcome at the Burning Man event. If you are planning to do fire art on the open playa, please see our Playa Art Guidelines for more information. To apply for a grant to fund the creation of artwork for Burning Man 2018, see our Black Rock City Honoraria page.

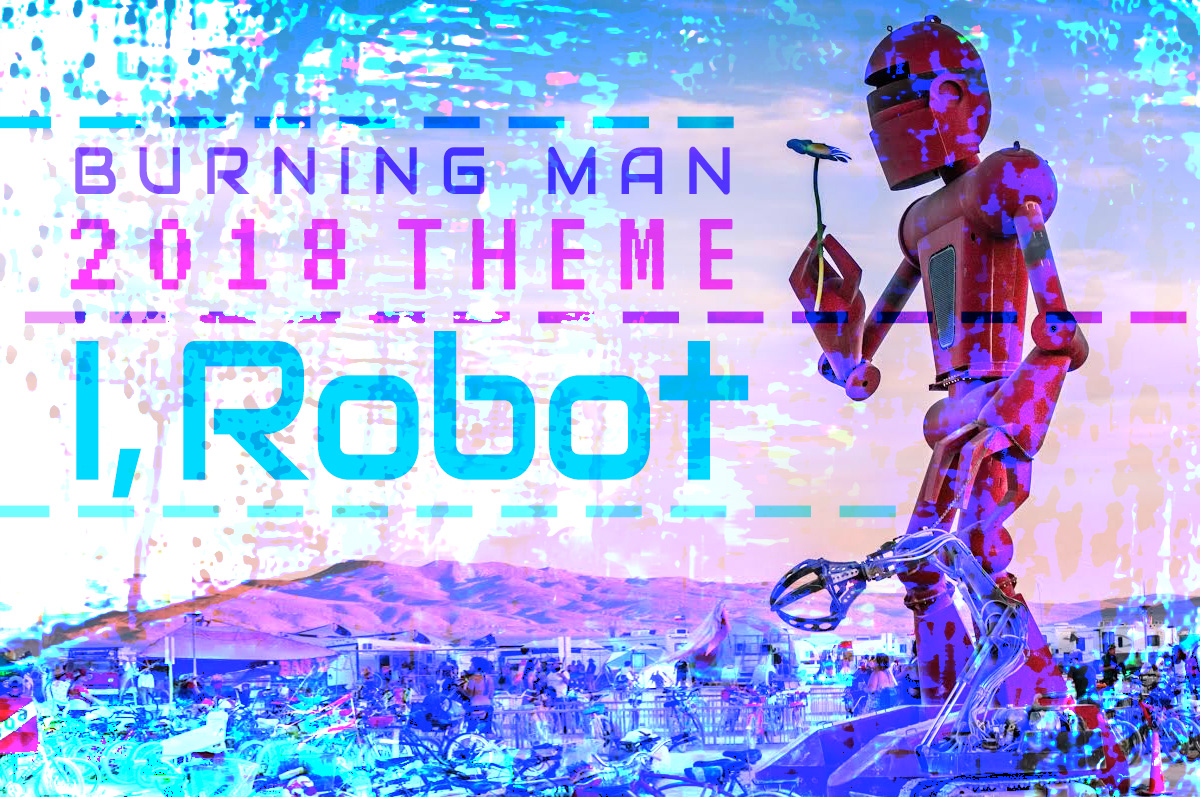

Top photo: Becoming Human by Christian Ristow, Black Rock City 2015 (Photo by Keith Aeschliman)