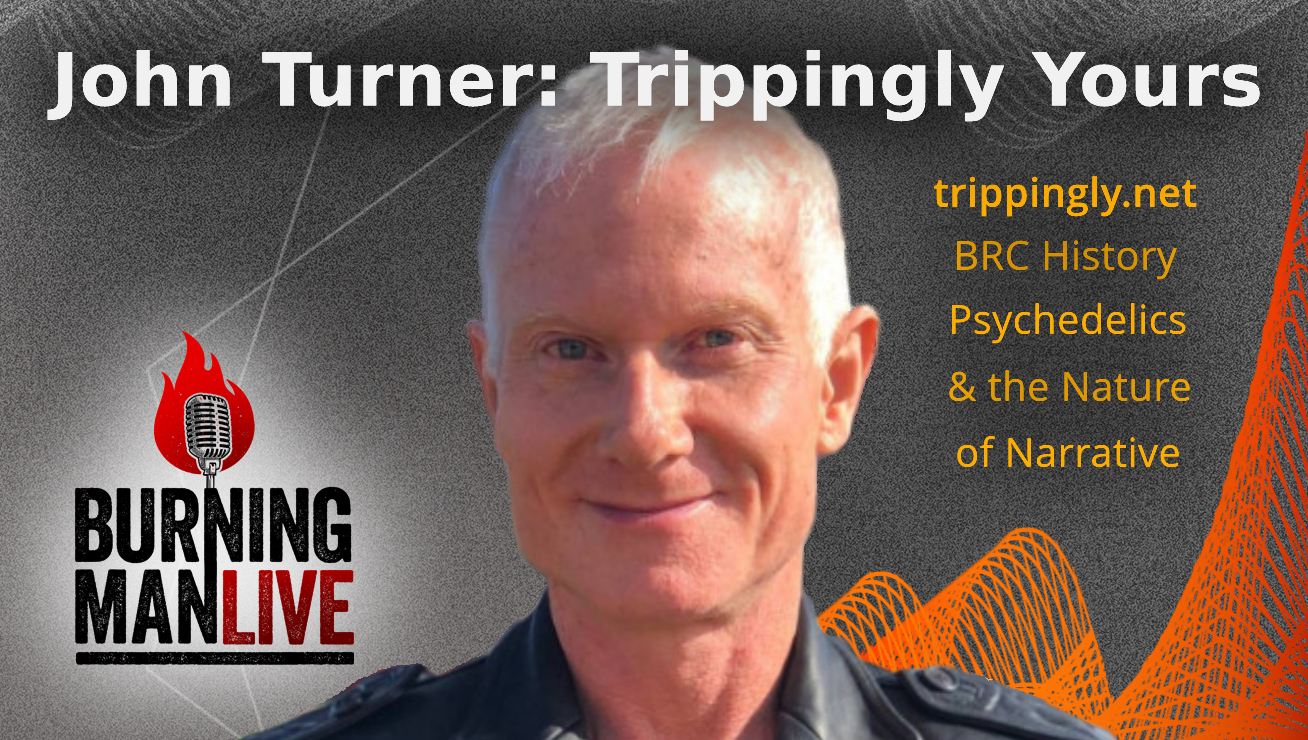

John Turner: Trippingly Yours

Psychedelics advocate and amateur Burning Man scholar John Turner’s two passions come together in one interdimensional rabbit-hole of a website: Trippingly.net. In compiling the ultimate fan site of Burning Man history, John has captured a lot of great playa stories, and he shares some of the best in this conversation with Stuart.

He explores the subjective unknowns of Burning Man events and psychedelics as same-same-but-different. Bring your neural nets to be plasticized. Bring your ego to be dissolved. It’s a trip through the past, and a trip through presence.

But when an interviewer interviews another interviewer, things can get weird. Together they explore the power of story (good and bad), who remembers what, who takes credit, and the subjective nature of consciousness. It’s a reflection on memory, serendipity, and the power of not knowing.

“Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” ~Mark Twain (as quoted by Larry Harvey)

Transcript

JOHN: That is the brilliance of Burning Man. I knew so many people who were involved in the founding of Burning Man, and had gone every year. And I hadn’t gone, but I was so confident I knew what I was going to experience. When I went, I wasn’t even enthusiastic. I was like, “I’m gonna go because a friend of mine wants to go, and I’ll go with them.”

I went there and I was blown away. I was like, “Wow, this is so different than what I expected.” And that was the magic. The magic was being absolutely surprised by it, absolutely disarmed by the experience.

STUART: Hey everybody. Welcome back to another Burning Man Live. I’m Stuart Mangrum and my guest today is, I would have to say, an independent scholar and historian of the Burning Man movement. He created the wonderful website trippingly.net, “dedicated to peak experiences” of both the psychedelic and other varieties, and certainly one of the very best Burning Man and psychedelics-oriented websites. Yes, it is those two things together. It is trippingly.net, and my guest is John Turner. Hey, John.

JOHN: Hey, how’s it going? It’s great to talk to you again.

STUART: Oh, it’s great. Yeah this site, it goes so deep, and in so many interesting directions. I gotta ask you though, at what point did you decide that you were so into Burning Man that you wanted to devote pretty much all of your free time into developing the ultimate Burning Man fan site?

JOHN: Yeah. Well Trippingly started as this psychedelics website. I would say it’s the first English language website that was just kinda, a pure advocacy website for psychedelics as opposed to a harm reduction website or a more general website. So I was investing in and becoming very passionate about decriminalization of psychedelics, and developed that website.

And then a few years later I had started to become very interested in the history of Burning Man. I had been friends with some of the old school people, and been lucky enough to meet John Law and Michael Mikel and some of the other founders, and was in a social circle with Chicken John and some of these quirky people, and they just had great stories. And I started recording things that I had observed, and I just started going on a deep, deep dive of how this all started and why it all started.

STUART: So you had not been to Burning Man when you started this process. Is that correct?

JOHN: I’d been there for one year, and it really blew me away as it does so many people. But then what happened was — this would be a rabbit hole to go down — there’s this guy called David T. Warren…

STUART: Oh, yes. Flame-O.

JOHN: Flame-O Le Grandé or whatever his name was. He’s just an interesting character, a tragic character, that really brought John Law into the scene. That was the story that started really fascinating me, his personal story, and that was just a little string that I started pulling on, and got down to the weeds, as I always do, into the whole birth of Burning Man.

STUART: Well, that’s a really interesting entry point. Dave was a pretty pivotal figure there, not only a Suicide Club member but also, I’ve heard people say that he was really the, single-handedly brought fire performance back from the circus. He had been a circus performer, been a carney, right?

JOHN: Right. Exactly. He was a carney, and a fire performer, and a magician, and a traveling brush salesman, and everything else.

STUART: Oh, where’s the long con anymore?

JOHN: I know, right? He just was a fascinating guy, and he really influenced a lot of people, and I think most of the people who have gone to Burning Man don’t have any idea who this person is, ya know?

STUART: Yeah, things didn’t end really well for Dave either, did they? There’s no retirement plan for old carneys and troublemakers.

JOHN: He had this very tortured existence. He became very deep into alcohol and became homeless. The real poignant thing about it is he grew up fairly wealthy, and he grew up in a nice house in the suburbs. And his family estate was kind of donated to the public to be a public park, and he went and lived in that park in a box. That’s how he lived his final sort of days, as I understand it. There’s some videos of him that John took, talking to him; being fairly happy, being fairly mentally not there, living in his family’s estate in a box. So you kinda can’t beat that for high drama and sadness.

STUART: So, what was your journey that got you to going to Burning Man and then deciding, “Hey, Burning Man needs an amateur historian to chronicle all that stuff and to put all that stuff together into a great website?” How did that happen?

JOHN: It’s a long story. I have a twisted history of growing up as a punk rocker in the 80s in L.A. and going to desert gatherings down south that were art festivals in the desert; showing up in 1999 in San Francisco, hearing about Burning Man and saying, “I’m gonna go to that.”

STUART: Did I just see a documentary film about that gathering in the Mojave Desert?

JOHN: The Desolation Center. Yeah.

STUART: When did you start putting this collection of stories together into Trippingly?

JOHN: I was hanging around with the people, the John Laws and the Michael Mikels, and the Chicken Johns of the world, and absorbing the culture of Burning Man. I had met Larry Harvey at a social function. I went into a little spiel of my thoughts about community, which was based in doing extreme sports, and getting really exhausted, kind of peeling humanity back to the core brain functions and hanging out with other people in that mode. He got very interested in that. He had someone from Burning Man send me the DVDs of things he thought I’d find interesting, you remember those kind of home-burned DVDs, which included the ABC 1997 Nightline special, and his own like art film he’d made back then; there’s a couple different things. And those things just kinda stuck with me. I had trippingly as a website already. It was already a really quite big psychedelic website back then.

I started just kind of writing things that I was finding interesting about Burning Man, and I just went down the rabbit hole of thinking about what happened here, and why it happened, how Burning Man happened. And that was how it all started.

STUART: The history section is pretty rich and pretty interesting. You’ve got a super complete collection. You’ve got all the founders in there.

JOHN: Well I’ll say, you know, I’ve always found you as being one of the interesting people because, you sort of had these archetypes of Larry on one side who was… Larry, I don’t know, I don’t like doing any characterizing necessarily, and then the Cacophonists on the other side who were these kind of punk rock characters. Larry was kind of a big word intellectual and the Cacophonists were kind of pranksters. And you were always a bridge between the two of them. You had brought this kind of intellectual firepower to the table that the Cacophonists had, but you also had some alignment with Larry. You were sort of interesting in how you filled the role in bridging those gaps. What was your experience there?

STUART: By the way, I think you’re doing a better job at interviewing me than I am of you, so…

JOHN: I am an interviewer, yeah!

STUART: When two interviewers interview each other, yes, it turns into a duel of microphones. For me, Burning Man and Cacophony were the same thing. I joined the Cacophony Society and the first event I went to was Burning Man. I met Michael Mikel, I met Danger Ranger, before I met Larry Harvey. The intellectualization of Burning Man is an interesting subject. Larry was always trying to search for what the deeper meaning was, but in a sense it was also a lot of obfuscation, because ultimately we both agreed, and I still insist: Burning Man is such a personal experience that the meaning has to come from your own direct experience of it. I don’t wanna tell you what it is, because that’ll interfere with how you live it.

JOHN: Well, great songwriters leave allowed blanks in the song for you to interpret, right? It’s not about what they’re telling you; the message is what the canvas is. And Burning Man, I think, at its best, is not a blank canvas – a canvas with some borders or maybe some numbers to color in. But it seemed like Larry was pretty consistent in giving a philosophical framework to it, to put meaning to it, to write about it in certain terms, whereas some of the other people, I think, were looking at it more as an adventure.

STUART: For me it’s always been about the mystery. It’s a place to encounter the unexpected, and the less it becomes that, the less interesting it is. If you knew exactly what was going to happen, why would you go? So that notion of experiencing something that’s very unlike anything that you’ve been through before (which actually I think is gonna be a little bridge into psychedelic experiences here, right?) It’s that notion of awe and wonder and otherness that can knock you out of your traces, so to speak, and that make you really experience the world in a more direct way. At least that’s what I’ve gotten out of it personally.

JOHN: What was most amazing to me about Burning Man was having known about it, and known the people who formed it and were involved for so long, how shocked I was when I showed up, how absolutely different the experience was than what I expected. And it was magical. It was an absolute surprise.

STUART: It sounds like you were talking to a lot of people who had stopped going a long time before, and had developed some rationales for that too, right?

JOHN: Yeah, both ways, though. Some of my favorite people though were people who kept going, like Philip Rosedale from Second Life fame was one of those guys who was like, “Every year is the best year.” That’s what I believe. Last year wasn’t my best year, but I hope next year will be.

STUART: Yeah, I don’t think last year was anyone’s best year.

JOHN: Yeah, it was lovely…

STUART: It was great to be back, and that’s the best thing you can say about it, right?

JOHN: No, I got Covid halfway through too, so that was great. It made it even warmer for me. Sheltered in place until the Burn, and then got out when I could. It was bad. It was rough.

STUART: But you’re not dissuaded. You’re going back this year.

JOHN: Oh, for sure. Yeah. This year and every year, I bet.

STUART: You’re a lifer.

JOHN: Yeah. It’s good.

STUART: So you still consider yourself a student of the culture. Are you interested in expanding on the historical database that you’ve begun?

JOHN: Yeah, absolutely. It’s funny because I just realized I had missed like an email from John Law, with his typical many pages of comments on something I’d written. John really likes historical detail the way I do, really likes the minutia. And so once I get those little things, I’m like, “Oh it’s fascinating that you remember that little tiny bit of who was on stage first and how this happened.” And that’s the kinda stuff I really like too. I get very obsessive about that stuff. So when I get like a little prod like that, then I go “Oh!” It brings down all these little threads I wanna start pulling on. Well, why did that happen? How did that band end up there? That’s really exciting for me.

STUART: I’m not even sure that my memory is any better than anybody else’s. There’s one article in here that I wrote, that I don’t remember writing, but it says that I wrote it in 1993, but I hadn’t ever been to Burning Man until 1993. So I don’t know, man. We’re getting to the point where I think it’s good to triangulate off of each other’s memories, right?

JOHN: Yeah.

STUART: There were a lot of ideas that came out of late nights at 1907 Golden Gate that were just sort of like that, and I don’t think getting past that circle and to an individual is really gonna be all that fruitful. When I ask them, they all just say the same thing: The idea came up when we were all together in 1907 with Miss P, and that most evenings there was a bit of a soiree over there. The importance of that little kitchen, literally and figuratively, to Cacophony can’t really be overstated. There was a lot of ridiculousness that gained traction there and turned into reality.

One of the things in the article I didn’t remember writing was something about how Cacophony would make you turn your words into action. You couldn’t just sit there and mouth off anymore about, you know, “Wouldn’t it be great if people did this?” That was the origin of participation as an ethic, as a driving ethic. Anybody can talk a good game. Anybody can come up with crazy ideas. But you gotta put yourself out there on the line, and throw a note in Rough Draft and see if anybody shows up.

JOHN: Absolutely. It was cool like how many different ideas came together that led to “Bad Day at Black Rock,” Zone Trip #4. These artists out in the desert before that, that Jerry and others went out and saw in the Black Rock Desert, and brought those ideas back to the Golden Gate house, and it all just coming together.

STUART: I want to talk to you though about how you reconcile stories that, as people get older and start to remember differently… I could quibble all day with fact checking on some of your stories. I don’t want to go into the errata. Usually the people will QA your work, as we say, right? You’ll get comments from people.

But how do you reconcile conflicting stories? Where do you find the one historical truth to write a history? How do you reconcile the Jerry James story versus the Larry Harvey story? The Larry versus John story?

JOHN: Well, it’s a great question because when I was early in the process, one of the things that was great about this website was I got to meet everybody, and I got to talk to these people. There’s a couple things that start giving tells of what probably happened. One is you kind of get credibility, you know, you kinda get people who are a little bit more gilding the lily, or just don’t have a very good memory, or you can sort of start seeing agendas. A lot of times I found contemporaneous videos, people had home videos of people talking about things in the 90s, and then those same people would tell a story very different 10 years later, 20 years later, either intentionally because they wanted a little different narrative, or people forget and they reconstruct things, ya know?

STUART: Well, they say we forget every time we remember; every time you unpack a memory and put it away again, it goes away a little bit differently. Do you ever experience the pronoun shift, where the “we” kind of turns into an “I” and people kind of, ya know, rearrange the contributions of others and their relative worth?

JOHN: I think I experience Burning Man the opposite more, where people probably deserve more credit, and they turn it into a “we” because a lot of this was a collective effort, and a lot of the little minutiae that I talk about probably aren’t that relevant. There are actually some fairly modest people involved in this whole endeavor, who like to spread credit around. So I see it the other way actually more. It’s kind of a lovely thing.

STUART: Yeah, and talking about stories mutating over time, you go into some pretty great depth on the origin story of Burning Man and Larry Harvey, whether it was about a lost love or whether it wasn’t; you’re absolutely right. His perspective on that changed a lot, I think, not in a continuous curve.

You talk about the difference between motivation and meaning, Larry not wanting people to confuse motivation and meaning. What does that mean?

JOHN: Right. I am convinced I know the story of the founding of Burning Man from Larry’s motivations and kind of what happened. And here’s why, I think, why Larry changed his story. I know Larry Harvey was struggling. He was in a dark place in his life in the mid 80s, and in 1986 he and Jerry James went out to the beach and burnt that effigy. I am confident that was motivated by a depression he was suffering. I’m confident it was motivated by this woman Mary, who was doing burns on the beach. I’m confident he was motivated by happy memories of a romantic excursion to that same location. And he said, “Let’s go do this as a way to spend the day.”

After that one happened, was, community was built. He saw… What Larry’s brilliance was, part of his brilliance was, he saw the potential for community. He burnt that little 10-foot (or whatever it was the first year) effigy, and he saw people gathering around, and he saw some significance. And then he brought something back bigger the next year and he saw a bigger crowd. The reason why he did it the first time was absolutely irrelevant to him, I believe. It filled a gap in his life, and it gave him meaning in a time where he needed meaning. So if you ascribe it to a lost love, or to a bad breakup, what was relevant to him was building a family and building meaning. What do you think, Stuart?

STUART: You know, it’s funny for us to ascribe motivations to anything that we do, particularly in a kind of a random creative act. It’s probably easier to go back and assign a motivation to it post hoc than it is to figure it out in the time that you’re doing it. I didn’t meet Larry until 1993. And by then, when I joined forces with him and started to talk about the event, we were very clearly in agreement that we wanted to intentionally not tell people what Burning Man meant, that the individual experience was fundamental to it, and that the more information that we provided to people, the less mystery and awe and discovery there would be in it; the less of them there would be in it. So that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.

JOHN: And that is the brilliance of Burning Man. As I said I knew so many people who were involved in the founding of Burning Man, and had gone every year. And I hadn’t gone, but I was so confident I knew what I was gonna experience. When I went, I wasn’t even enthusiastic. I was like, “I’m gonna go because a friend of mine wants to go, and I’ll go with them.” I went there and I was blown away. And I was like, “Wow, this is not what I expected. This is so different than what I expected.” And that was the magic. The magic was being absolutely surprised by it, absolutely disarmed by the experience.

STUART: Well, here’s to having a little bit more awe and wonder and mystery in the world. The more that I think about it, that’s just really at the heart of it, right? It’s not what you expect, and it doesn’t map to any of those expectations that we all carry around so dearly for us of what’s going to be, what’s going to happen next, and next, and next.

JOHN: You know, there’s a phrase that I always heard in Burning Man, but I hear it in psychedelics a lot. I hate it in psychedelics, but I love it in Burning Man: The playa doesn’t give you the experience you want, It gives you the experience you need.” I think that’s really true. People also say psychedelics don’t give you the experience you want, it gives the experience you need. It doesn’t map as well there.

STUART: Well, yeah, there’s the set setting and dosage model too, right? What mindset do you bring to it? Black Rock City can be a great setting for a successful psychedelic experience, but what did you bring with you? What’s already operating in your mindset? Speaking of psychedelics, that is the other side of Trippingly, and you mentioned that’s its original purpose. Tell me what it means to you? What is your career like as a psychedelics advocate? That can describe a lot of roles in the world. What section of that do you find you’re adding the most value to that cause?

JOHN: Well, I don’t know about adding value, but I can tell you about my day-to-day life because it’s really all over the map. I started out as someone who was taken aback by how effective psychedelics were at healing my old trauma.

I took psychedelics the first time with a friend thinking this is gonna be a fun experience, and it turned out to be a fun experience, but it uncovered a whole lot of things that were in my head that I didn’t even know. And so I started using this and found it very healing for me. And that became why I started writing the website and advocating for decriminalization in Oregon. And I then became active on the business side of it as well, investing in and advising venture capital funds and for-profit and nonprofit companies in the space.

I was a lawyer for 20 years. I really don’t work for a living anymore. I just don’t wanna work. I wanna do fun things. So my job is really pontification.

STUART: Hey, wait a minute. What’s the IRS job code for that? Cause I should probably put it on my tax return too!

JOHN: Yeah, right. It’s a good one. So I kind of sit on conference calls and try to say wise things now and then, and try to bring in some experience as a lawyer and some experience as a psychonaut,, and whatever I can. I’m a little bit of an odd mix because I had a traditional career, really, and so a traditional corporate lawyer in Silicon Valley at the biggest firm, and probably the most conservative firm; at the same time where I was very deeply involved with psychedelics and other drugs and compounds. But my day’s fun! I talk a lot and think big thoughts.

STUART: So that’s a great second career story. You leaned into your freak, and brought it to the forefront,

JOHN: What really moved me was I had personal healings with psychedelics, and I got lucky that a legend in the field, Amanda Fielding, who was really the person who gave birth to a lot of the science behind what we’re seeing now in psychedelics; the treatment of treatment-resistant depression, she happened to reach out to me. It’s kind of like a legend tapped me on the shoulder, and you don’t say no to that. I just got pulled into the deepest of the pools immediately with these OG people on psychedelics, and these big thinkers. And I looked around and said, “How the hell did I end up in this room? This is a great room to be in right now.” So I just keep tap dancing and hope no one notices.

STUART: Alright!

JOHN: I work for the Alexander Shulgin Research Institute, which kind of invented all the cool drugs, and popularized MDMA. Alexander Shulgin was really the legend. His wife Anne Shulgin and he created most of these really interesting compounds. The Institute continues on. It’s out there developing new drugs.

It’s a different world now. In the old days, Sasha would invent something, try it with his taster group, and then publish it openly. And now you know, it’s a big business. So people are doing this commercially for FDA approval. But there’s lots of new compounds being developed, some for just pure therapeutic purposes, and some are pretty interesting compounds on the subjective effects they have.

STUART: So, you mean, recreationally?

JOHN: I’m a big fan of recreational usage of drugs, but most of the stuff, honestly, because of the finances now is that the stuff is being done for big budget commercial purposes. Some of it obviously has some really cool side effects, like, you know, LSD, for example. But there’s also ones that are being developed to have no subjective effect, and that’s the appeal: a psychedelic that you don’t feel anything, but have the underlying mechanisms working where you may have neuroplasticity, is very appealing. So you have people who don’t want to have a psychedelic experience, but have brain damage, traumatic brain injury, other things, hopefully benefit from this kind of work — and hopefully it will blow some people’s minds and some cooler other stuff too.

STUART: Tell me more about that. I wasn’t aware of that. I thought pretty much they always had the subjective effects, so to speak.

JOHN: You know, Sasha developed 500 compounds that we know about. A lot of them had no subjective effect and were kind of put aside. But a lot of them are doing things at a subconscious level or a physiological level. We’ve obviously recently learned what we always suspected is that these are probably very beneficial to brain structures. Now the world’s in the process of investigating what these compounds are going to do.

But you can imagine if you are looking at psilocybin as being something for treatment resistant depression, you know, psilocybin experience, your magic mushroom experience, typically lasts five hours, and can also be very psychologically engaging. Therapists would love that to be shorter, a two hour experience. Therapists love to have that available to people who can’t or don’t want to have a traditional psychedelic experience. So you start playing with molecules, and you start trying to make those experiences shorter. We’re finding out whether non-subjective psychedelic trips are going to have the same benefits as classic psychedelic trips. That’s a hot area of research, a hot area of finance.

STUART: Well, certainly a lot of psychedelic research informally has been conducted out on the Black Rock Desert. People talk about it being a transformative experience, how many people do you think really are saying that they had a great trip out there?

JOHN: They had a great psychedelic trip at Burning Man? I would say a lot.

STUART: I mean, Burning Man has been described as so many things. Is it a trip without drugs?

JOHN: It’s a trip, but I mean, it’s different, right? For sure Burning Man can be magically transformative and wonderful without any intoxication whatsoever. I was totally non-intoxicated the last trip and still, I had these amazing moments. But it’s probably not a psychedelic experience.

STUART: Well, I’ve done it both ways. And it’s been a long time. I wish I had some of this great information back when I was a punk high school kid, just deciding where to split that four-way pane of Mr. Natural. The dosage guidelines too, which I wish I had known… Oh, religious patterns or iconography. What does that mean when people report that? I have a vision in my head, but what does that mean in the literature?

JOHN: Let me tell you about my personal experience instead. People often have a religious experience, or they perceive religious visions. I was absolutely an atheist before I started taking psychedelics. I don’t know where I am now, but let’s say I was absolutely an atheist. And I took my first high dose psychedelic and suddenly I saw Islamic iconography everywhere. I saw mystical images. And in my very psychedelic state, I was like, “Wow I bet on the wrong horse here.” And I really was kinda shaken about how strong this religious imagery was for me.

And then I came down to my non-intoxicated state and started processing it. What did that mean? Did I really have visions of God before me?

And then it gets to the debate that people often have, which is: maybe what we are doing is creating a religious state, or maybe the people who created a religious iconography and images were experiencing transcendental states, on psychedelics or through meditation, through deprivation, and were seeing the same kind of visions.

It doesn’t answer the question if there’s a great creator or not. It just says where these images are coming from? Is it somehow imbued in our brains and somehow revealed by psychedelics or by starvation or whatever? So what came first is not clear, but certainly the visions of iconography are very common.

STUART: For people to see the same geometric mandalas, and all that, when I was a punk kid, we used to call them the Aztec patterns. Maybe it was growing up in L.A. but they reminded me and my friends a lot of some of the iconography you’d see in MesoAmerican pyramids.

JOHN: People take high doses of the DMT and often have like little space gremlins whispering in their ears, or robots, or whatever it is, it’s a little different. Depending on what drug you’re going down, you might have a different kind of machine elves, right, popping up.

STUART: For some reason, lots of people who go to Burning Man are very interested in psychedelic research, psychedelic advocacy. In fact, my friend Ray Allen, who was our general counsel until very recently, just took a job as the head lawyer over at MAPS. There does seem to be some connection there. And why not? Ya know, over the years, I’ve tripped in a lot of places, but I have to say the desert out there, particularly when you have some space and a moonless night and a lot of sky above your head, not that that ever happens during Burning Man anymore, but that could be one of the more soul opening sorts of experiences.

JOHN: I do think there’s something magical about Black Rock Desert itself. I mean, I really am one of those people who believes in the magical vortex of Black Rock. It moves me anytime I’m near.

STUART: So in your ongoing Burning Man research, have you ever been really surprised by anything that you found out?

JOHN: I like the personal stories. I really like soap operas more than I like historical stories. I’ve heard these personal stories when people open up. One thing I found is when you really get into the weeds, you bring people back to their childhood or to their upbringings, they start remembering things, and then they start opening up. They also have the psychedelics, they open up to you when they find out you’re in psychedelics professionally. So I’ve had people tell me these stories that they’ve said that I haven’t talked about in 30 or 40 years. Some of them were quite shocking. One of them was quite shocking, you know, but it was so personal that it wasn’t newsworthy, it wasn’t relevant to the website.

STUART: Yeah. That is a dilemma. Burning Man is a million very personal stories, and sharing a personal story involves a measure of trust that can’t ever be assumed.

JOHN: The story of Jerry James and Larry Harvey is a really interesting story. But even what the public stuff is, there’s this interesting interplay between a friendship and then professional betrayal and personal feelings, and then a beautiful attempt at reconciliation at the end of Larry’s life, where things were under the bridge a little bit. And then Larry had a stroke. Jerry James, one of the founders of Burning Man, essentially, reached out two days before Larry’s stroke to get together and it just never happened. But there was a reconciliation there that was kind of beautiful. And those are the personal stories I love.

STUART: That is poignant. Some of these relationship stories, which will probably never be reconciled like the John Law and Larry Harvey story; I wrote a little bit of a Burning Man history for new staff onboarding, and when I got to that part, I realized that the only really way to express that relationship was operatically.

So I pulled in one of the arias from How to Survive the Apocalypse, the Burning Opera, which is the showdown between the Larry character and the John character about the future of the event. It is the stuff of high drama or opera.

JOHN: I think the two people are so different. It’s amazing. They spent time together. They both have lofty ideals, but they’re very different in their beings.

STUART: I met them on the same day in the offices of Central Sign over in Oakland. John and I have done a lot of adventuring outside of Burning Man, and had a lot of great times together. I would never downplay… You’ve talked about Larry being the intellectual…

JOHN: Oh. Larry is a form of intellectual, he’s a big-word intellectual.

STUART: John can think his way out of a paper bag too, and have some very strong opinions about things.

JOHN: John is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met in my life; the form of raw intelligence I most respect; one of my favorite human beings on the planet.

STUART: Well Burning Man as we know today certainly would not exist without either of them, right?

Without that inner plan, without that tension, that dynamic, we wouldn’t be where we are.

JOHN: Burning Man would’ve ended in 1996, I believe.

STUART: It would’ve ended in 1990, ya know, if Larry hadn’t run into the right people.

JOHN: Yeah. This is the kind of stuff I love. You look at motivations, and Larry’s motivations were critical for the event to survive. And look what we got. I’m very grateful it happened.

STUART: A lot of people are.

JOHN: Yeah.

STUART: But it’s complicated. So what else do you wanna talk about, John?

JOHN: The Philosophical Center: How the hell did you end up there? That is a very Larry Harvey idea. This is not something I would see you quickly signing up for. Am I totally off base there? Or where did this, how did this all play out?

STUART: Well, I’m no philosopher, John, and it never pretended to be. I like to think I’m more of a practical thinker and a storyteller. Yeah, it was definitely Larry’s thing. The story is that when the nonprofit was being put together (which was the beginning of Larry’s succession plan, right?), he didn’t want it to turn into your generic nonprofit, board-run whatever. He wanted to make sure that those principles were carried forward into the future, and used, if not used to shape and guide policy, at least as kind of a guardrail on policy.

So he referred to the Philosophical Center as “The conscience and collective memory of Burning Man.” Conscience in the sense of holding onto our core values, which by the way, are all Cacophony values except for Civic Responsibility, which I’ll still hold as a child of necessity.

And the collective memory, somebody’s gotta hold the stories. You know, ultimately, in X years from now, all that’s gonna be left are the stories of what happened out there, right? Of the people who went out there and changed it and were changed by it. That’s my passion. I’ve always loved a good story, and when Larry passed away, I did not hesitate to step into that, to hold that space, to hold that portfolio.

JOHN: One thing I’ll say for sure is the whole idea of themes in Burning Man, I really appreciated the themes you’ve brought out post Larry’s death. I think they’ve been great.

STUART: Really?

I did not like the themes of Burning Man. I don’t think that was a good idea from day one, but all of a sudden you started doing it…

STUART: I tried so hard to talk Larry out of it!

JOHN: Really? Okay. It seemed like a little cheesy.

STUART: We heckled him, heckled him out of it, but he just kept on doing it.

Well, thank you. I’d like to say it’s fun, but it’s really hard and really lonely work. You know, when we used to do it together, it was fun, and painful and nerve-wracking. Our styles are very very very very different.

You know, a lot of artists are gonna do whatever the hell they want to do, and that’s fine too. We always say that. But, particularly for people who are newer to creative pursuits to have something to kind of pin their star on and say, “Alright, we’re gonna go in the direction of… furries for instance!”

JOHN: Oh, that’s next year, I’ve heard. Is that leaking right now? That’s great. Fantastic.

STUART: No, it’s this year. That’s the shorthand version, that ANIMALIA, is really the year of the furry. I have no problem with that because I actually have great respect for anyone who can dress up in a fursuit and dance at 110 degrees. You’re an athlete! That should be an Olympic event!

JOHN: It’s funny, you talk about Larry’s writing and one of the things that when I was first working on the website and digging through some of the old writings, now Larry would kind of interview himself under his nom de plume Darryl Van Rhey. You also used it, right?

STUART: Yeah. Early on, as I was Tom Sawyer-ed into the Burning Man world, it started with publishing the newspaper out on site, and then it was “Oh, you know we do this other newsletter during the year. It’s called ‘Building Burning Man.’” And he had already used the Darryl Van Rhey thing because he thought it was shamefully egotistical to just, you know, flat out interview himself. It just felt weird. So he created this anagrammatic reporter persona, Darryl Van Rhey. Then I just kinda stepped in naturally. It’s just like, “All right, I’ll write some questions.” So my questions became Darryl Van Rhey. And then after Larry passed the first theme I wrote was published as Darryl Van Rhey, because it just seemed too soon.

JOHN: That was the first time I was confident it was you also using that. There was just a very different writing style.

STUART: A lot of us came out of that zine world, the late pre-internet era. That’s how I fell into the Cacophony Society was swapping zines with Rough Draft. A lot of the people that came out there in the way back were zine publishers that I was connected to. So the Monks, the folks from Big Rig Industries, from Chuck Magazine, from Cardhouse. In ‘96, actually I, because I was running the radio station and the webcast and the newspaper, and wanted to have a life, I just basically had an editor of the day for the three days of publication, and they were three of my best zine publisher friends. Those issues are all still on the site. I got them all digitized. So I still have fun going back and look at those.

JOHN: I love reading those old issues and it puts you back in the, you know, what it was like to be 1993. It’s just a very different attitude, like Church of the Subgenius, all these kinds of things that were floating around that led to the Cacophony Society, that state of mind, you know, the Suicide Club to the Cacophony Society, this kinda zany fun that people were having, and zine culture pushing it. It’s a good trip down memory lane.

STUART: It’s true. You know, San Francisco in the 90s was the intersection of a lot of creative forces, a lot of economic forces too. It was still possible for people to work a part-time job and still afford to live in a reasonably good style.

JOHN: It’s an interesting journey. It’s an interesting journey.

Let me ask you a question. Why did you come back? You left like in ‘96, right? And then you started getting pulled back in, I assume by Larry.

STUART: Yeah, Larry called me kind of out of the blue in like, 2012. He was writing the Cargo Cult theme and he wanted me to help him. I was at a point in my life when I had some time on my hands and even though I’d sort of taken John’s side in the big divorce I’d stayed friends with Larry. And so I came in to work on the theme. And one thing led to another. It was the old Tom Sawyer. Give him a little bit of worm and then rope him in. Next thing you know I’ve got a desk, and I’m commuting to San Francisco. I’m not sure how it happened.

JOHN: I think a lot of people have a story about Burning Man. They don’t know how else they end up working there. I think enthusiasm is the common answer, you know. It seems to be a little cultural magnet that pulls people in, pulls them back just when they thought they were out.

STUART: Yeah. I think it’s fascinating that, for years you were a vicarious Burner, that you experienced Burning Man culture through your friends, who were some of the early organizers.

JOHN: I was real fucking busy. The idea to go into the desert for weeks seemed like a lot of work. So it was not practical.

I was going up to Nevada City and hanging out with the Founders at the hotel party they were doing there every year. I was meeting and hanging out with key people from the old school, hearing their adventures. I felt like, “Oh, I get it.”

And then I went. I was like, “Fuck, this is not what I thought. It’s so much more interesting.”

STUART: And it doesn’t get any more convenient. Burning Man is still inconvenient and potentially dangerous.

JOHN: Yeah. It’s certainly not Disney World, despite what some people say.

STUART: Disney World wouldn’t let you die of heat stroke.

JOHN: Well, I also like at Burning Man that you’ll be climbing on some piece of art and you’ll like to see blood stains. You go, “Okay, well, I better be careful about that.” You know, there’s no warning sign other than human flesh. That’s probably pretty sharp. That’s keeping it real.

STUART: Lizard brain on high alert. Outstanding. So in addition to all of the great historical content on Trippingly about Burning Man there’s also a whole lot of practical tips. We could easily spend an hour just going through that, but maybe you could just sort of pick a favorite tip for each of these categories. You ready?

JOHN: Yeah. Okay. Well, I’ll do my best.

STUART: Okay. Tickets!

JOHN: Tickets. Um. Be prepared for disappointment. Join a good camp. Be part of the community. Do your best to get the lottery, and believe you’re gonna get that ticket. And, tell everyone you want a ticket. Tickets always seem to come through in the end.

STUART: And hopefully not a counterfeit ticket because those exist.

JOHN: I know. It’s sad. Don’t buy ’em off of eBay!

STUART: Do not buy tickets off of eBay. That’s… No matter how good they look.

JOHN: I’ve never gotten a ticket through the website. By the way Stuart, I’m looking for a ticket. If you have an extra one, you know someone who does, or anyone’s listening, he has an extra ticket. I could use an extra ticket.

STUART: I’m sorry. I’m sorry. Vav, I think John’s connection is going dead.

JOHN: Yeah, exactly.

STUART: Okay. How about packing? Some people refer to Burning Man as recreational moving. Got a good packing tip for us?

JOHN: Yeah, I think there’s very different games if you are doing an RV pack versus a tent pack. If this is your first Burn, you don’t need to bring nearly as much clothing as you think you do. And then probably bring extra water and things that you can gift to other people around because people are gonna run out of water, people are gonna run out of food. Bring some extras of those kind of things.

STUART: Batteries and cigarettes. Even if you don’t smoke.

JOHN: Batteries are a good thing.

STUART: It’s like prison, you know? Batteries and cigarettes.

Okay. How about food? I love to eat out there and I hate to cook out there. So what do you do?

JOHN: I make a lot of quesadillas, that’s a real easy thing to do.

STUART: Yes!

JOHN: And I just go out to Thai restaurants. I get meals from my favorite Indian, Thai curry places, and I freeze them and I microwave them. It’s delicious and it’s so easy to do, and if you can heat it up, it’s no work.

STUART: I think quesadilla is the champion food. Try this next time: Pre-make them, freeze them, you can just thaw them on your dashboard of your car. There’s a hot piping, hot cheesy snack for you on your dashboard by one o’clock in the afternoon.

JOHN: I usually freeze some pizza as well, and you can eat anywhere between cold to melted or whatever. Easy stuff to do.

STUART: Like a pizzasickle?

JOHN: Yeah. It never tastes bad.

STUART: You’re an RV camper. You got a good RV tip?

JOHN: I have a very, very clean RV, and the way I do it is I put rosin paper down on the floors and I change it out every two days.

STUART: It’s just like craft paper, the brown ground craft paper in a roll?

JOHN: You get this like a brown paper, tape it down with some painters’ tape and you keep changing that stuff and every just keeps things clean.

I’ll tell you my guilty thing I do, but it’s so great: I bring a humidifier. So when you walk into my RV, even if it’s warm, it’s still a little bit humid. It keeps your nose nice and breathable and it makes your skin better. This little $20 humidifier.

STUART: Moist and muddy.

JOHN: Moist and muddy.

STUART: How about getting there, and dodging all the potential hazards of the road?

JOHN: Well, thank goodness I drive from Portland, Oregon, not from L.A. or San Francisco, so I can tell you the drive from Portland’s real easy. You’d see a couple Burners on the way, and there’s no traffic, and I can time it where I can get to the Gate exactly when it opens, so there’s usually not a line at all. If you’re from Portland you don’t need any tip, or Seattle, it’s just an easy drive. If you’re from L.A. well, you know, move!

STUART: Everybody in L.A., you heard it here, just freaking move!

JOHN: But not to Portland, please.

STUART: Well, that’s already happening. Getting through the various roadblocks, or not roadblocks, but you know, speed traps, or obscured-license-plate-traps…

JOHN: There’s an article on the website all about that. The police look for any excuse to pull you over depending on what you look like. As a psychedelics advocate, believe it or not, I am actually a target of law enforcement from time to time, so when I’m driving my RV, it is not obviously a Burning Man RV. I don’t have a big Man taped on the outside of my RV. I put the bikes inside, and it kind of looks like an old dude driving an RV. I’d be careful. Don’t block your license plates. Make sure that the license plate is lit up.

STUART: And never consent.

JOHN: Never consent. Yes, there are articles on the website. “I do not consent to a search.”

STUART: As one old freak to another, that’s almost worth a tattoo on your arm. I do not consent. Actually, there’s a whole section of the site on drugs at Burning Man. What’s your drug tip, Mr. Psychedelics Advocate?

JOHN: Don’t take drugs from strangers. Don’t give drugs to strangers.

Test everything you take, and bring your own supply. Bring the very minimum that you are gonna personally use, so if you do get stopped or whatever, you have something that’s not worth anyone’s trouble.

Use in moderation. I think Burning Man’s a place where the police won’t bother you unless you’re creating a scene. But if you create a scene, you’ve seen it, we’ve seen it, where 20 cops come out of nowhere and descend on somebody. So be thoughtful, and pace yourself.

STUART: All right. My guest today has been John Turner. His fabulous website is trippingly.net. Thank you so much for being on the show, John.

JOHN: Thank you.

STUART: I will see you in the dust.

Burning Man Live is a 100% decommodified production of the philosophical center of the nonprofit Burning Man Project, made possible by the generosity of listeners, perhaps like you, who kick down a few bucks now and then at donate.burningman.org. Thanks, thanks a lot to you. Thanks to all the unusual suspects: Michael Vav, DJ Toil, Action Girl, kbot, Deets, Kristy-not-Brinkley, and as always, thanks Larry.

more

John Turner

John Turner Stuart Mangrum

Stuart Mangrum