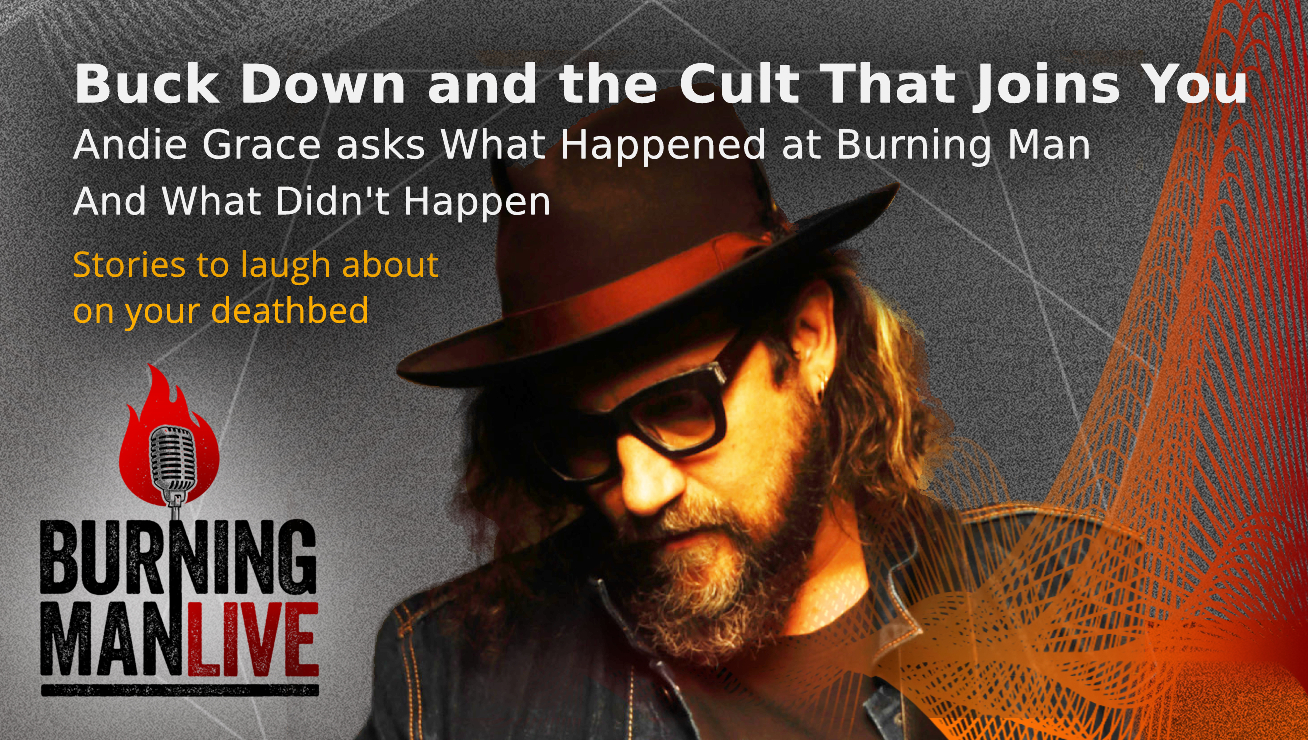

Buck Down and The Cult That Joins You

What happened at BRC? What didn’t happen? Why did it seem that we couldn’t get back to interdependence?

After the traumas of the pandemic and political vilification, we somehow didn’t trust each other at BRC. Or if we did, we didn’t seem to know it, or feel it, or enjoy it.

Andie Grace swaps stories with Buck Down, a 25-year Burner, Gate Manager, musician, and author of the wildly popular article “What the Fuck Just Happened at Burning Man?”

They spitball on how to encourage more play, work, and random participation, and how to split the event into two.

Black Rock City changed underneath us. As stewards of this culture, let’s remember the parts of the culture that had us commit to it. Let’s make this ‘cult that joins you’ worth it.

FYI: This episode is fun and full of curse words. And as always, the last part is the best.

https://buckdown.medium.com/what-the-fuck-just-happened-at-burning-man

https://buckaedown.bandcamp.com

Our guests

Buck AE Down is the Black Hole Operations Manager, Gate Perimeter and Exodus. He designed the Burning Man event ticket in 2008 and 2014, as well as the official event poster in 2016. He was a founding member of the Mutaytor and the Gentlemen Callers of Los Angeles, and was once the Mayor of Gigsville, along with scores of other odd jobs around Black Rock City for the better part of the last 20 years. He is a regular contributor to the Burning Man Journal, BRC Weekly and “Piss Clear.” He lives in Altadena, California with his wife, kid and a Bulldog named Floyd.

Transcript

BUCK DOWN: I’m very happy to talk to my dear sweet friend Andie.

ANDIE: Well, it’s a real pleasure to get to talk to you today, my multi-talented friend, Buck Down, who I’m proud to introduce, is a musician of renown, a designer, a Gate volunteer or staffer.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. Management.

ANDIE: Management. A Manager of Gate. Oh. Let’s talk about that. And an overnight social media influencer with his recent article, “What the Fuck Just Happened at Burning Man?” How’s that feel?

BUCK DOWN: I get to break the internet about once a year, and it’s always cool. A lot of it just, I fight with algorithms like we all do, I think that people that put art online do.

At the end of 2019 everybody was doing their sort of ‘wrap up the decade’ pieces, and I wrote a piece called “The 2010s, the Decade of Shitty White People,” which, talk about a click bait title, and then that did like 150,000 reads on Medium. This one that we’re talking about today is just over a hundred thousand which is comparable.

ANDIE: It’s pretty new, so, yeah. What do you think is different about it? What do you think hopped the fence this time?

BUCK DOWN: The big thing was that it made it onto the Burning Man Facebook group, which has a quarter million people on it; some percentage of all the people who have ever gone to Burning Man are on there.

ANDIE: Many who haven’t as well, I note.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. It’s like three things. It’s the clickbait title, one.

Two. I think that it really spoke to something organically, a question; everybody was like, “What just fuck just happened there?” because it wasn’t the same.

And then three, it’s that the Burning Man community is very networked, and so like, yes, while you and I probably have the same 500 people that you know, generally are localized to people who have worked at the event, or people that can draw themselves back to say the early 2000s, late ‘90s, but there is also a bunch of Burners who are farther afield, now that we’ve had enough people come through that event; millions now.

ANDIE: Well, and, and, Burning Man is not just in Black Rock City, right? There’s regional burns.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. And then I think you also have the phenomenon that all of us come out of there— we come back from our “company picnic” and then we wouldn’t shut up about Burning Man for the other eight months to anyone that would listen.

So on some level, it’s the closest thing Burning Man has to advertising is the fact that we all go out there and then just don’t shut up about Burning Man. And then it’s probably appealing to… 20% of people go, “Oh, that sounds great.” The other 80 are like, “You’re fucking insane.”

ANDIE: “Will you please shut up?”

BUCK DOWN: Yes. “Would you kindly shut up about Burning Man?”

ANDIE: That’s why you called it the cult that joins you.

BUCK DOWN: It is. This is a holdover to Cacophony (Society), the appeal of Cacophony was that one line, ‘you’re already a member, you just didn’t know it yet’.

ANDIE: You may already be a member.

BUCK DOWN: You may already be a member. If you had gotten that far to have heard that line, odds are yes, you were. And I think that most of the places that I’ve found myself connected to, which are the same ones you are, Gigsville is very much like that, Gate is very much like that. And different departments within Burning Man are very self-selecting because I think, Burning Man does very much let you fail laterally until you find the place that you’re useful.

ANDIE: Facts.

BUCK DOWN: I’ve gotten to the point where I’ve spent so long, particularly working for Gate, I can talk to somebody for 15 minutes and tell them which of, I think 26 sub-departments we have that they are going to be awesome in.

Because all of the people that roll to that point of gravity have certain things. The people that work Perimeter, I can tell who a Perimeter person, because they’re kooky and antisocial on some level, they’re smart, but suck at people, you know? All my Perimeter friends who are listening to this are going “Fuck you, but also, yes.”

ANDIE: “Great Buck, I’ll see you next year.” Punch.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. I’ll pick a fight with a Perimeter guy. Here’s the thing, somebody from Logistics absolutely punch me in the face. I remember the guy. But then the people that work the lanes, they’re just gonna bitch about it on Facebook. See what I’m saying? It’s like all of the individual little things within Burning Man have that.

ANDIE: Let’s go back to your article for a second. I wanna talk about the unique experience of this year, and how you noted and identified the internalized trauma that we’ve been through being so isolated from one another, and for some people this was their first big meeting with anybody. How did that come into play for you this year?

BUCK DOWN: Well it definitely was me. I was the patient zero on this article. I’ve been doing this now for 25 years, and in particular, working for the department I’m working for, for I guess 15 now. So I’ve got a pretty broad data set of what Burning Man generally feels like. This stood out. I walked away from that trying to reverse engineer. I was like okay, what’s different?

When I got back and I saw other people intimating the same things, there was a trend line that I could follow which was that the longer that you had gone to Burning Man and the deeper that your involvement was, the more this phenomenon seemed to stick out.

From there it was just kind of working backwards. I’ve been working with the same people out there. We’ve been out there roughly the same amount of time. We have all the same friends. We’ve been in that world for a long enough time to know, for the most part Burning Man’s Groundhog Day, especially if you work there. When you get there, the things that make any individual year differentiate itself from any other one don’t exist. So it’s the same shit that you have in your containers, and you set your camp up the same way, and you do your process the same way.

ANDIE: And that couch I donated 10 years ago. Yeah.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. We are creatures of habit. I have this sensation every year when I get there that I just fell asleep in my LC at the end of last year, and had this dream about Los Angeles, and now I’m back at work at Burning Man. Like I never left because so much of it looks exactly the same; it’s the same people. We’re all kind of at that cusp of early middle age where we don’t look that different every year. Maybe a little fatter. By the way, that was my goal for Burning Man this year, was like, I don’t need to not be fat. I just need to be not any fatter than I was the last time everyone saw me, so the first thing they think is like, “Oh yeah, you got fat.”

ANDIE: Oh, I thought you were gonna say you packed on a few on purpose which would be a really noble goal because people deserve to look however they feel like taking up space.

BUCK DOWN: Well, there’s the fact that I’m not willing to put that much effort into it.

To bring it back to the question. Yes. Looking at the relationships that I had with people and relationships among people, like within my department, community, however you wanna phrase that, that had known each other, in some cases as long as 20 years. And you can see palpably different reactions to one another and the seeing things that would have normally happened and have happened in the past. Obviously something is different about it.

The whole point of the article was starting to drill down and go like, what was it?

Well, the weather was shitty. Yeah, the weather’s always shitty.

It was hot. Well, it’s always fucking hot.

It was hard. It’s always hard.

The things that were everybody’s first guess, I was like the worst those things are the better. Under a normal year, if it was super shitty, we’d be bragging about how super shitty it was.

ANDIE: True.

BUCK DOWN: That’s the kind of people we are. We’re not going there because it’s easy. We’re actually going there because it’s hard, and this is sort of a privilege-canceling exercise.

ANDIE: Well, especially in your milieu, your cohort in Gigsville, which is one of the longest standing villages in the whole town…

BUCK DOWN: 25 years.

… is full of people who volunteer their butts off like you do, and give much of their lives to bring in, not just on the playa, but contributing design like you do and things like that, and who are somehow willing to make Safety Third and Sufferfest a priority.

BUCK DOWN: There are very few remaining institutions that can go all the way back to the late nineties, early two thousands; obviously Thunderdome is one of them, Gigsville is another. It’s certainly still the longest running village. Actually, I think Gigsville was kind of the first thing that transitioned from being a theme camp to what we now call a village.

ANDIE: Multiple theme camps.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. Multiple theme camps. Oddly enough, Gigsville of all people, um, sort of established the contours of what we call a village. That started around ‘99 and there’s a very direct line between the LA Cacophony Society and Gigsville.

It’s funny because Gigsville has probably put more people into the deeper seams of this event than any other village has, and the vibe, the rep of Gigsville, which I adore — and it’s not undeserved — is that we’re idiots and we’re here to bum everybody out and, or just to fuck with everybody.

Gigsville is just that do-ocracy. There’s never any pressure on anybody to do anything, and as a result, you can choose to do things. That is the way you get people to… no one wants to be micromanaged, especially out here. These are not followers, you know.

ANDIE: Right.

BUCK DOWN: It is a self-service cult. Like Larry said.

ANDIE: Wash your own brain!

BUCK DOWN: Wash your own goddam brain, everybody.

When you do that, this is one of the reasons why with my music, I make it ‘pay what you want’. I have made more money selling music to people by going, you know what? Pay me whatever you want for that, inclusive of nothing. Taking that pressure off of people to have to do things puts them in a space where they’re more inclined to want to do things. There’s enough options out there to where you can pick the thing, like, “Oh, this is interesting to me. I wanna go stand in car exhaust fumes two miles outside of the best party on Earth,” or whatever it is.

ANDIE: Right? I think it was Très Gauche of Gigsville back in the day that said, “If you launch an idea and nobody wants to help you with it, maybe it wasn’t a very good idea.” That’s been really the do-ocracy of Gigsville the whole time.

BUCK DOWN: Or it’s not a bad enough one, you know.

ANDIE: See also “Carbeque”

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. We’re not doing this because it’s smart. And I think that is a sort of a vestigial tail from the early, ‘92 to ‘96 era Burning Man, where it’s just like, “Let’s do things that are cartoonishly dangerous and stupid,” which I think is, we all discovered not scalable!

ANDIE: That’s a perfect way to say it. I heard that the fire department got called when the Carbeque got lit this year.

BUCK DOWN: That’s a fine tradition.

ANDIE: It’s a fine tradition indeed. So anything that you wanna share about how it went at the Gate this year?

BUCK DOWN: The Gate, it’s funny. If you take three to four steps back, 30,000 foot view of the event, nothing didn’t happen. All the deliverables got delivered. A Man burned, people got in and out of there, all the stuff in the “Who What When Why” probably happened.

ANDIE: I like the “why” that you added there. What, Where, When… Why!

BUCK DOWN: It really does need a “why,” doesn’t it? That should be part of when you submit an event. Like “What are you doing? Why?”

ANDIE: I don’t know!

BUCK DOWN: They don’t know. Not because it’s smart.

Yeah. All those things happened, but I think it’s that they weren’t as rewarding. That would be the closest thing I could say to like an axiomatic thing. We did all these things, but why did I not get the dopamine release, the feel good brain juice, that normally happens here.

One of my things my individual sub-department does in Gate is the Opening Night Ceremony. At the stroke of midnight. You know, we stop all the traffic, we shut the lanes down, and then blow up a giant fuel bomb and some fireworks and yay Burning Man starts. We bring some folks down in art cars and stuff like this. It’s the longest run for the shortest slide imaginable.

But normally that’s a thing within my crew of like 13 people that exhausts a lot of effort and labor, but when it’s done, we’re all like high fives and “Yeah, we did that!” This was the first year that that was not the way we came back after that. And no one was talking to each other, which is unusual.

There are some moving parts in there, like everybody else. We had a lot of turnover. We had a lot of people in jobs that they’d never done before. It’s not happening in a vacuum. Still, the good feeling didn’t come afterwards. Why is that not happening?

So much of what Burning Man does is this shared experience, this shared thing; this thing we do together. What I think had happened to us over the pandemic was: we very much got back into the thing that Burning Man had dragged us away from, which is this rugged individualism, this unhealthy selfishness.

A lot of what makes Burning Man work is this exercise in interdependence. I think that we were not capable of shifting gears back from independence to interdependence. In the pandemic we all turned into a dirty bomb. Everybody you met, particularly before vaccines became at least an option, everybody you ran into could have killed you, or could have given you the tools to kill somebody that you love.

I don’t think anybody really wrapped their head completely around how traumatizing that was. Whether we knew it or not, subconsciously, we were aware at some level that other people represented an existential health threat. Then we all come out there like that hadn’t happened for two years.

What that did was made it so that it was harder to trust people that we were close to because the nature of how this pandemic worked was like you could be carrying a thing that could kill the people closest to you, and vice versa. That eats away at the foundation of trust that we have for each other. Because Burning Man is this kind of trust-fall exercise facially, at a really high level, if you think everybody’s going to kill you, you can’t… Those screws are loose now. And so it’s not surprising that it comes apart.

ANDIE: Do you see any solutions to that as we anticipate returning to BRC?

BUCK DOWN: Um, I don’t think that this is permanent damage. Unfortunately we are now swimming with a current that’s been kind of going on in this country since 2016, maybe farther back too, this sort of tribalism, and this civil war that we’re in, that’s the convergence of how the social media algorithms work, that sort of rewards that, like, “Let’s fight. Them are fightin’ words. I’ll see you at the flagpole after school, punk.” That sort of thing where a lot of our social interaction now is kind of built off of these performative displays of conflict.

A big thing is acknowledging what’s going on. I think there are two things that work here that have a synergy to them, which is the unprocessed trauma from the pandemic turning every one of us into this sort of insulated self-protection bubble. And then the other one is the nature of like “Pick a team. Whose side are you on?” And then like, as soon as you pick your team, then you erect all these sort of moats and walls around it, and it becomes a very binary choice of either you completely agree with me, or you can eat shit and die.

That kind of factionalism, I think for what we’re trying to do at Burning Man, which is to kind of create this interdependent society that ostensibly has a diversity of opinion, and things like that, and tolerance, and, it’s seeped in there too. I don’t know that it is as extreme as what we see in our body politic in America, but it’s not zero.

ANDIE: Do you think that’s because certain people don’t feel welcome in that environment?

BUCK DOWN: Uh, I think Burning Man is jarring enough. The hostility of the desert itself has always been enough to overcome that. That’s kind of the point. We created a common enemy out of the heat, or the desert, or the lack of plumbing or whatever it is, that kind of pasted over whatever minor differences we had with one another were pretty easily pushed off to the side by the fact that if we don’t get out of the sun, we’re gonna die, and I can’t build the shade structure on my own. So that’s kind of the solution. It’s trite to say it, but there’s nothing wrong with Burning Man that what’s right about Burning Man couldn’t fix, if we can get back to that level of buy-in.

ANDIE: Wow. That’s actually really smart.

BUCK DOWN: I read a couple books.

ANDIE: What keeps you coming back?

BUCK DOWN: That’s a great question ‘cause that was one that haunted me on the drive out. Like I said, this was 25 years straight, minus the two years we weren’t there, but I was still working for the event online. Mostly just arguing about COVID for two years, and as we all did what we should all do, and how this is not gonna work, and who gets to be blamed for what. But a lot of it was like trying to like, “Why am I still doing this?” This is not, I mean, it’s fun, but it’s not fun. You know?

ANDIE: We can be in Tahiti relaxing at a beach with some umbrella drinks.

BUCK DOWN: I’ve toured enough in bands and whatnot to know that there’s a great big world out there full of way-cool shit that’s new and novel and fun. The answer I came down on, when I finally got there and spent a couple days: It’s about a hundred people.

There’s about a hundred people out there that I’ve known and been working with for most of those 25 years that are among my favorite people that I’ve ever met in my life. And the version of themselves that they get to be at Burning Man is an accelerant on the things that I love about them.

Moreover, you don’t have to make plans. I’m just gonna run into these people, like it’s just gonna rain all these people on me and all my interactions with them are gonna be these relaxed, random interactions opposed to like, if I came up to your town, we gotta find parking, you know?

ANDIE: As opposed to, “Hey, it’s you.”

BUCK DOWN: Hey, it’s you out at the trash fence. What it allows for is a kind of interaction that gets us away, and I think especially so many of us come from these overcrowded feeder cities that are a hassle to go out in and meet somewhere. And then look at the interaction you have. It’s like, “Okay, I’m coming up there. Great, we’ll go out to dinner here.” So now we gotta make plans. We go there, and then we got whatever, however long we can keep from…

ANDIE:I’m terrible at this.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. All of us are. That’s the other thing too. I think that there’s something about all of us that sucks at that particular thing.

ANDIE: Especially when you have kids and a family.

BUCK DOWN: Oh yeah, throw some kids in there. The time we do get to spend with each other, we’re just eating at some Thai place or whatever. I’m not gonna get to see you push yourself to the best version of yourself over Pad Thai.

But I can do that at Burning Man. Like, “Oh, Andie’s rad. Look at Andie being rad. Look at the situation that Andie got put in where you can be the legend that you are!” It allows us to kind of be these versions of ourselves that we always sort of knew was there, but you know, the older you get, you gotta do some shitty job with people you don’t like, and then just day after day it grinds you down. Not me. I’m smart enough to not do that, but most people.

It really does put you into these situations where… We started off with this discussion of, like, “Let’s pretend we’re building a city.” But then we actually were building a city. And then it’s like, “Oh, look at these things that we made were real.” Because again, we are in a situation where if we don’t do them, the consequences are dire.

ANDIE: Right.

BUCK DOWN: That’s what’s important about it. So to answer the question, there’s about a hundred people that I love seeing in that situation. And even if I saw them outside of there, I can’t see them perform at that level. And more importantly, I can’t.

ANDIE: I never thought about it that way, watching people manifest their best selves in the face of all that. And yet, maybe that’s why I left feeling frustrated and why your article resonated so hard with me was, I felt ineffective on that front for the first time in — I’ve been doing this for like 25 years too.

Yes, the weather kicked my butt, and all of that, but there was this other kind of elephant in the room, that we were just not used to doing what we do, and the systems had all changed because of the turnover of the last few years. Really everybody I met and everybody I interacted with was throwing themselves at it, including my a hundred people, you know, my 150 favorites. And yet when you would run into them, they just kind of looked a little drained and a little exhausted; and that was true not just for like staffers, but people running theme camps, and artists, and everybody. It was just hard to be amongst people again like that, and taking off the moth balls.

BUCK DOWN: This is like the two years of not doing it probably putting its thumb on the scale, and also the fact that there was so much turnover that you had a lot of people having to stand in these gaps if not doing some new position entirely.

One of the things you gotta do when you’re a manager at Burning Man is, after Burning Man you gotta call everybody on your staff and do these debriefings. One of the most common things that I’ve been hearing back was this feeling that people had, like, “I don’t know if I did a good job. I don’t feel like I performed at the level that I like to perform at.” And it’s not because anybody was going, “You fucking sucked at that, bro,” although some of that did happen, but you’re not getting that dopamine rush that comes from “I did it! We did it!” It was this feeling, this wildly unsatisfying feeling like, “I feel like I got a C on this test.”

ANDIE: Yeah, which is for the average listener who’s a participant probably hard for them to parse because, “Well, do a good job or pay people,” or whatever, but it’s a different environment. We do this because we love it, and being ineffective at it is a mortal wound in a lot of ways.

BUCK DOWN: Most people at this point, you know, when you’re in 10, 15, 20 years – I don’t even know that it’s even it anymore. It’s the people. I can tell you amongst the people I work with, it’s not dissimilar to people who do multiple tours in like Afghanistan. It’s like, “I don’t know that I necessarily believe in this war anymore, but I’m not letting these people that I love go do it without me.” And honestly if that’s the case, Burning Man’s doing its job. Burning Man is decentralized enough to where there’s not some central ego, some god whose ego needs to be stroked. It really is about the friends we made along the way.

The feeling like we let each other down.

ANDIE: Yeah. Really real.

BUCK DOWN: I think that’s fixable, and I don’t know how much of that is a thing that has to happen inside each of our own heads and hearts versus a thing that can be externally demonstrable.

ANDIE: Damn.

BUCK DOWN: The analogy that I have made, which is not necessarily the most apt one because it’s ridiculous to think that what we’re doing out there is any way or shape or form like the stakes of war or anything like that.

However, there is a mentality of people who keep coming back to that: You are bound to, less the cause as time goes on, and more the people you do it with. And for people who walked away from this feeling like “I didn’t do a good job, I let people down.” It’s not that you did, it’s that it felt that way, which is almost as bad.

A number of the people I work with, and a lot of people out there who, their love language is words of affirmation, and if there’s one thing Burning Man is exceptional at, it’s saying thank you. That card we get at the end of the year, is the most important thing, for a lot of people is getting that thank you. All of us want to feel like we earned that, and something inside of us didn’t let us access what was clearly the gratitude of our coworkers.

Every day I had conversations with people where I’m like, “No, honestly, you’re doing great.” But for whatever reason that didn’t gain purchase. And I don’t necessarily know why that is, other than that connective psychic tissue that we have of a shared thing.

The funny thing about this article and this conversation is: When it’s done, I don’t know that anybody felt better.

ANDIE: They might have felt more seen, ‘cause I certainly did.

BUCK DOWN: Well, yeah, I got a lot of that. I think as an artist, your job, your real job, is: You’re supposed to articulate these axiomatic feelings that people have that they don’t necessarily have the way to compress into one great sentence. That’s what a writer does or a musician does. That’s the thing you’re constantly trying to get at.

I’ve been making art professionally my entire adult life. I don’t know that I’ve had as many people react that way to anything I’ve done that they had to this particular art. The feel good was like, “Thank you. This is everything that I’ve been feeling that I couldn’t put my finger on.”

ANDIE: And that had to be beyond just staffers. We’re talking about many thousands of people.

BUCK DOWN: Oh, it’s everybody, across the spectrum. That’s the other thing is realizing that when you work there, you do tend to end up kind of backstage. And even if you go out to Burning Man, there’s still this beaded curtain between you and the experience, just because at any given moment something could go sideways and you could get jerked right outta Burning Man and go deal with some dumb thing. It’s hard to totally let yourself go to it. By the way, this is why staffers do short-duration drugs. Nobody could commit! Nobody could commit!

ANDIE: Those were the days!

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. Who’s got 12 hours that you could burn anymore?

ANDIE: So when you get home, do you ascribe to “Don’t change your life drastically after Burning Man?” or did anything change when you got home?

BUCK DOWN: Don’t divorce your pigeon?

ANDIE: Don’t divorce your parakeet.

BUCK DOWN: Don’t divorce your parakeet. Fortunately, I’m aware enough of that axiom to where I don’t – this is what I’ve been telling everybody during these wrap ups. I’m like, “I know the temptation to say you’re quitting or taking a year off next year is strong right now. And I’m not saying don’t have that, but maybe revisit that in January.”

ANDIE: Harley used to not accept resignations between October and January.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. There’s something about the new year. It’s actually because of how our calendar works. You get out of Burning Man, then you have debriefs, and then there’s that rush to get your budget in for next year. And then the holidays come, and then we actually have the one break we all take. And then around January 1st, it’s time to start calling everybody and see if they’ve found something better to do with their life.

ANDIE: The art grant process is already open. We’re heading into 2023 already.

BUCK DOWN: Right around the time the event started selling out.

ANDIE: 2012ish.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. There was effectively no off-season. That was the end of the off season. There used to be a pretty clear demarcation. November, December, there was that gap where like, “Okay, we’re all off the hook till January,” or whatever, but that went away. It’s a continually running thing now.

The other thing is, time dilates in this really weird way between like, “Oh, next year I’m gonna do this.” Like while you’re in the middle of something failing, like, “Oh, this failed. So I’m gonna just make a note to myself that this failed. We’re gonna do this differently next time.” It is now a year-round event in some ways.

ANDIE: I will never stop saying it was better next year.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. You know what my one is? It’s worse next year.

ANDIE: It’s worse next year. Everything will be okay in the end if it’s not okay, it’s not the end. Oh wait, no, it’s already all okay.

BUCK DOWN: MmmHm. Yeah. It’s fine. No, it’s bad on purpose. That’s the thing you gotta remember. It’s bad on purpose. You gotta let go with this notion that any one year of Burning Man is quantifiably different or better. It’s not.

The process of doing it together is the art. When we first started doing this, when everything burned, the whole point of it was: We are going to erase all the effort we just made because we are trying to keep the focus and the priority on the process of doing it, not the thing that was done. That was a very foundational, philosophical, North Star that we were all pointing to.

The goal here is not to make a thing and have everybody be reminded after our death that we made this thing. The idea is like, “Great, look at this awesome thing we just busted our ass doing. Now let’s destroy it!” And the glory of doing it, that just manifests itself a little differently. That’s a thing we’ve lost sight of.

And there’s other things too that I feel like where we may have lost our way a little bit.

ANDIE: Example?

BUCK DOWN: Okay, I’ll tell you one. This is an Org-level thing: The notion that all the art needs to be done on the Monday right after we open the gates. It used to be, people were slapping together art all week. The projects…

ANDIE: Some of it never got done.

BUCK DOWN: Some of it never got done! That was the thing is, you could just show up there, not connected to anything, and walk around and see some ding-dongs unloading a box truck and go, “Hey, whatcha doing there?” And it’s like, “We’re gonna build this penis sculpture. You wanna help?” “Sure.”

There were all these opportunities for volunteerism in the actual art that happened in real time that was the secret sauce. That’s what we meant when we said “No Spectators,” “Participate.” You can walk around and find something that somebody’s doing, and work together.

Now, it seems the priority is on this, like, somebody comes out there the week before, builds this thing, and then you go and interact with it on an entertainment level. That breeds Spectatorism. By making it so that all the art is built and done on Monday, there’s no chance for anybody to come in and participate other than like, “Check out this hat I bedazzled.” We really got away from doing that.

We used to have one principle, not 10. Two actually, “Leave No Trace” and “No Spectators.” That was the whole of the law.

ANDIE: Okay, but you were a founding member of Mutaytor, which was one of the earliest performance groups on the playa with a large group of performers that welcomed a lot of participation from the audience.

BUCK DOWN: That is true.

ANDIE: And as a performer, certainly a show needs spectators, so tell me about that.

BUCK DOWN: You can’t the circus without the rubes, you know. At the same time, look at what Mutaytor was. Mutaytor was about 30 people, and the way that that formed is one person sitting in the middle of the dirt playing drums and somebody walks along and goes, “What are you doing?”

Playing drums.

“Can I play drums?”

Yeah.

Okay. Now two people are playing drums.

Somebody goes by, and is like, “Oh, can I spin fire to that?”

Yeah, you can spin fire to that.

Somebody else comes along and is like, “I’m good at making a baloney sandwich. Can I make a baloney sandwich while you do that?”

Absofuckinglutely. We’ll put a light on you.

That was the point. The whole ethos of The Mutaytor was this turning-civilians-into-rockstars mentality. If we can do it, you can do it. You didn’t have to be especially great at what you did to get into Mutaytor, but the nature of what we were doing, there was a Tao to it, like Spectator Camp. Remember Spectator Camp?

ANDIE: I do, with the bleachers where you can just watch it go by.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. For those of you that are under 60 or whatever, one of the most dominant things that we were all religious and shitty about was like “No Spectators!” Somebody could jump up your ass if they thought you were spectating.

So these geniuses came up with an idea to put some bleachers alongside the Esplanade where you got there and you literally, they put a big klieg light down on there, and you spectated hard together. You just judged everybody that came by and yelled at them. And it was awesome. I used to just make whole nights of it.

They took the one rule “No Spectating” and made it the most participatory thing you can possibly imagine, and that’s it. The secret sauce, the magic of Burning Man is just that. You could leave your tent, go wandering around, and then find yourself involved in this participatory thing that you had no idea an hour ago even existed, because in some cases it didn’t.

Some of the most fun I had in the nineties was making up some bullshit like “We’ve got these four safety cones. Why don’t we put ’em in the middle of the road and then we’ll put shot glasses on them and see if we can get people to drive by and do a shot while driving a bike,” which, half of them ended up chucking it in their eyes, which was fucking hysterical. That kind of thing. Next thing you know, some people set up camp chairs on the other side to hold up scorecards that they made.

I’d rather see a playa full of that, than somebody’s overproduced $500,000 ego trip. You bring out something with massive production values, and you had to hire skilled contractors, and while that is great, that’s not gonna change anybody’s life the way spending an afternoon yelling at strangers in a bullhorn, trying to get them to do some ridiculous thing.

ANDIE: Street improv. My favorite part.

BUCK DOWN: Street improv. Schtick. When you came back, and you wouldn’t shut up without Burning Man, those were the stories you told. You didn’t tell them about, “Oh, I saw this massive sculpture of the thing.” It was like, “Oh, I sat down with some people and played a game called ‘Does It Go in Cheese?’ where we just took a bowl full of cheese and stuck stuff in it and tasted it, and then decided, does that go in cheese?” Ms. Roach came up with that one. We did that at the Black Hole.

ANDIE: Which is the kind of story that has your non-burner friends looking at you like “Uh-Huh?”

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. That’s why I go back to the 80/20 rule. 80% of the people will think that’s the dumbest thing they’ve ever heard. The other 20% of those people will quit their jobs to do it the rest of their lives.

ANDIE: Absolutely accurate.

What have I not asked you that you wanna make sure to mention?

BUCK DOWN: I think maybe it’s time to unpack some solution. I feel like I did a fairly decent job in the article pointing out the problem. What it is light on is solution. Like I said, we need to get our rando participation game back up.

I feel like we’ve lost a lot of the improv in things that we were doing for totally legit reasons, like, “Yeah, somebody should build this thing right, and there should be some accountability to it.” I mean, I remember climbing in stuff in the ‘90s where it’s just like “We’re all gonna die in here. This was made by cracked out amateurs.”

ANDIE: Right. But we made it through.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. It’s like the ‘70s, like ”Seat belts. We didn’t wear seat belts.”

ANDIE: Those of us that lived.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah, right. All the dead ones aren’t there to fucking pipe up, are they? I think we need to rethink what participation means. If you have only been coming since, let’s say the sellout year, which is a very big… two geologic epochs are separated by that event.

ANDIE: Absolutely.

BUCK DOWN: Because you used to really have to wanna go to Burning Man. It was not for everybody. And there was enough space and enough room to accommodate all of that. And now we are just doing crowd control. So much of what we’re doing as an organization is just trying to keep these 80,000 people from dying, you know? And that’s great, but at what point are we just a NASCAR event?

Maybe it’s time to reconsider the idea of doing two 40,000 person events, separated by 10 days. Something like that. We have definitely discovered there are parts of Burning Man that are diminishing returns, and not scalable past a certain point. And I feel like the magic number for Burning Man is probably somewhere around 40,000 people.

It’s just like a dinner party. You can have too many people at a dinner party. Or what is it? Dunbar’s Number.

ANDIE: Which is 150 people, right?

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. Dunbar’s number is that there is a number of people past which any org chart will break down, and it’s been true for org charts going back to like the Roman Legion and everything like that.

The basis of it is, troupes of apes. So in ape societies, the social network is grooming. That’s how they connect to each other and that same thing. After 150 or 200 apes, some apes are not getting groomed, and then they become un-groomed, unruly apes that disturb the balance.

It’s the same thing with people. You can only maintain… it’s probably somewhere between 150 and 200. It’s probably bigger now that we have social media and can…

ANDIE: I don’t know if it really got any bigger for our brains though. Maybe slowly, but…

BUCK DOWN: You can’t maintain but a fixed amount of relationships where you’re close with somebody just because there isn’t enough time to know all those things about them, to be involved in their lives, etc. And I think that there is a number for Burning Man as well. The experience starts diminishing in terms of like, if we wanna go back to first principles, about what you should be able to get out of Burning Man. As the number gets bigger and bigger, we’ve made this sort of dividing wall between the quote unquote artists, and everybody else.

The artists come out and they’re doing participation. I bet you that number’s close to 40,000. The number of people working a theme camp, participating at the level of participating that we socially decided was Burning Man “participation.” And then you have the other 40,000 that are literally just walking around taking pictures of themselves in front of other people’s art.

Gosh, wouldn’t it be great if we could go back to something that was a little easier for somebody to jump in on? At 80,000, because of safety, because of the stuff we have to do, we are sort of pushing them farther and farther into like, “Hey man, just go over here. Try not to get run over.” We’re forcing them into a life of spectatordom.

If it was up to me, it would be about trying to make this a little bit less ambitious, art-wise. I love that we spend what we do on art, but I don’t know that the bigger, more overwhelming things necessarily… Again, I think it’s diminishing returns. I would far rather see people come along and make shitty art together than a handful of people make some big piece of art, and then everybody else just stand around and take Instagram photos in front of it. That to me is the difference, insofar as anybody’s interested in my opinion about quote unquote what we should all do.

If you look at our production arc and you look how long we’re out there from July to October, it is entirely possible, because especially… So I get out there somewhere right after Fence Day, I’m out there for a month. There’s an entire other Burning Man that happens before we open up the Gate. And it is two separate events in some ways.

ANDIE: Many people describe that as their favorite part. There’s some meaning there.

BUCK DOWN: Right, because, what’s going on? Everybody out there is doing something intentional. If you’ve got a WAP, if you’re out there, you are participating.

ANDIE: The Work Access Pass, for those that don’t know.

BUCK DOWN: Yeah. And then the non-WAP people, there’s no incumbency upon them to do anything other than bedazzle a captain’s hat or whatever, and try not to get run over. How do we go back to where we cleave that in half the same way and make it so that it’s all WAP? All “Get a bucket and a mop.”

ANDIE: I wonder though, a person coming into this for the first time, putting on a clown nose, and they’re wearing jeans or khakis otherwise, and the clown nose is the most radically expressive thing they’ve done in years. So maybe it’s their first entry. But you’re saying that getting to be able to do more, not just express more, but actually physically do more, would also matter.

BUCK DOWN: You can wear the clown nose while you pound T-stakes, you know?

ANDIE: Yeah. But for some people, that’s a really radical act. They’re super uptight and they are afraid that somebody’s gonna see them and they don’t want their picture taken, and they put it on, they feel ridiculous, and then they walk around with it on all day because it’s Burning Man.

BUCK DOWN: I will posit to you that being asked to help make an art does more to fix that problem than sticking a clown nose on. And you can do the first one with the clown nose on, which is actually pretty important. Like, “Here, put on this clown nose and help me build this dumb thing.” I think we need to get Burning Man back to being what it is, before we open the door to people without a Work Access Pass.

Everybody should be out there, like we should make it so that we can network people into building art together. There needs to be a premium placed on art that’s built during the week, and could be built by people that didn’t know each other before.

That’s how we all met, all of us that are still here 25 years in. We’re still here because 20 years ago you saw some dummies doing some ridiculous thing and go like, “I would like to do that ridiculous thing.” And they were like, “Sure, come do it.” And those are all my best friends now. And all those are the people who work at the event now. We need to make it so that people that come in get that treat. To make Burning Man continue to be relevant the way it was, we have to figure out how to get back to that.

ANDIE: I can’t argue with that, Buck.

Any final thoughts?

BUCK DOWN: I actually do wanna say thank you to everybody who reached out to me through text messages or DMs or smoke signals or whatever, that took the time to write me back and say, “This had an impact on me.” You made an old head feel good. Um…

And thank you to everybody that remembers the way this used to be. I know it’s not the back-in-the-day “You should have been there, man.” thing. We can redirect that energy. If Burning Man was better 10 years ago, well great. Why was it better 10 years ago? And what are you doing right now to make it so that that can be like that for the second-year sparkle pony?

ANDIE: Yep.

BUCK DOWN: As village elders, we are stewards of this culture, and I think that because the event changed underneath us, because of—housing costs alone had a big impact on it, and who gets to go to Burning Man, and all that. We were like the frog in the frying pan on a lot of this. But, it’s still our responsibility to remember the parts of the culture that made us drink the Kool-Aid.

If we’re gonna make a cult that joins you, let’s make the cult worth joining. That only happens when a stranger can come into a situation and make an art, whatever that is. It’s the work, you know.

All these people that are coming in—the bucket listers—are shooting themselves in the foot. It used to be that we came out to Burning Man, and it’s like we were on this “versus nature” trip, right? Where it’s like, “Okay, we’re all gonna figure out how to at least fight the desert to a draw.” Now you’ve got people that are coming out here like it is a display of how well you can live out there. It’s like, “Oh, I’m gonna bring a Michelin chef and I’m gonna live in this 50-foot Prevost rockstar RV,” and all this other things, and like, “Look how great and fancy and nice everything is that I have out here that somebody else built and I possibly paid them to do.” You are never in a million years going to get the thing about Burning Man that we got, that is the reason why we’re still here. You cannot get that, that way. You’re not going to get the good stuff.

I feel like if we prioritize that part and remind people like, this is the shared thing that we do together that’s going to give you the friends you’re gonna have for the rest of your life, and it’s gonna allow you to see the thing that you laugh about on your deathbed, that’s how you get there.

ANDIE: Beautifully said. Well gosh, thank you so much for being here today.

BUCK DOWN: Thank you.

ANDIE: We’ll see you next year, I’m sure. Whether we like it or not. We do!

BUCK DOWN: We do. Apparently! Thank you for having me on, and keep the faith, folks.

ANDIE: My good friend, thank you so much.

BUCK DOWN: Thank you, my good friend. And Vav, thank you for refereeing.

VAV: Awesome. Thank you so much.

BUCK DOWN: All the best. Aloha, friends. Bye-bye.

ANDIE: Hey, Vav…

VAV: Burning Man LIVE is a production of the Philosophical Center of Burning Man Project made possible by generous donations from listeners like you… and listeners very different from you, too. Give at Donate.burningman.org

Thoughts? Feelings? Intuition? Let us know at LIVE@BurningMan.org

I’m Producer and Story Editor Michael Vav. Andie Grace produced this episode. Thanks to our teammates kbot and DJ Toil, and to the Philosophical Center’s Director, Stuart Mangrum.

And thanks Larry.

LYRICS:

Keep you eyes

Up to the azure skies

Don’t let the carrion flies

Follow you home

more

Buck Down

Buck Down Andie Grace

Andie Grace