Monique Schiess and AfrikaBurn

As a founder and co-producer of one of the largest and oldest Burning Man events, Monique Shiess has a lot going on. AfrikaBurn does too. Started in 2007, it averages 10,000 participants annually in recent years.

Monique shares its origins with Stuart and Andie. From the EDM scene, gallery spaces, queer community, and producers of “weird gatherings,” they birthed AfrikaBurn with roots in anarchy, trickster energy and hippie-dom.

They explore how to be welcoming, not just radically inclusive, in the aftermath of Apartheid, and the context of global trends, on the land of indigenous people.

Then there’s the fun part. Monique says that play is the vector for changing the world by accessing aspects of yourself that go dormant in the default world, and that all Burn movements have paradigm shifting potential while also having a ton of fun with “the best humans that exist.”

Transcript

MONIQUE:

When I went to Burning Man, I was like, okay, well there: fun and play are the vector for change here. Because fundamentally all these changes that we are talking about, and I don’t mind if your Burn is just about coming and having an immersive dance experience, I don’t mind. But for me, it’s about changing the world. And you do that by accessing aspects of yourself that go dormant in the default world.

STUART:

Hey everybody, welcome back to Burning Man Live. I’m Stuart Mangrum and I’m here this time with my good friend and cohort Action Girl, Andie Grace. Hey, Andie.

ANDIE:

Hello, Stewart.

STUART:

Nice to be here in the same imaginary studio with you.

Our guest today is someone I’m pretty excited about. She is one of the founding organizers of the largest Burning Man event outside the United States. I know some of you’re going to go, “What? Do we even have that? Is that even a thing?” But I’m very, very glad to introduce you to Monique Schiess. Hi, Monique.

MONIQUE:

Hi. Nice to be with you guys.

ANDIE:

Hi.

STUART:

So why don’t we start at the very top because like I said, some of our listeners are probably going to be scratching their heads right now saying “What? AfrikaBurn? What is that?” Go ahead and just give us a little bit of overview please.

MONIQUE:

Yeah, so AfrikaBurn is obviously an offshoot, a regional event of Burning Man, and we had our first event in 2007. We got a really big fright because there were nearly a thousand people there and we were maybe expecting about 200. So yeah, we’ve been going for nearly 16 years, and very often gets introduced as the biggest burn outside of Burning Man, but I think size doesn’t matter, and I think MidBurn was actually about to overtake us at some point. But yeah, for some reason the thing exploded in South Africa and it’s just been an absolute rocking ride, a joy and exhausting and a surprise, and all the lovely things.

I would also like to argue with you that when I was at Burning Man this year, the only thing I ever heard was “AfrikaBurn, AfrikaBurn, We got to go to AfrikaBurn,” so I think people do know about it.

STUART:

Okay, great. I might have been one of those people saying that because ever since I met you years ago and heard about it myself, it is top of my list of regional events to go to.

MONIQUE:

Well, come on over, man.

STUART:

Okay, well tell me a little bit, set my expectations. So tell me about the place, how it’s going to be similar to what I’ve experienced in Black Rock City? What’s different?

MONIQUE:

The question that I get asked a lot is around what is different about AfrikaBurn compared to Burning Man. Besides obviously the question of scale. It’s a lot smaller, although it’s a big Burn. We topped out at fourteen and a half thousand people, but that’s us limiting our numbers. We limited our numbers because of the capacity of the team, and we also didn’t want to become victims of our own success, too rapid growth, et cetera. Where was I?

STUART:

Driving out there and I’m not driving through a desert. I’m driving through… is that the veld?

MONIQUE:

The veld, yes. It’s in a desert called the Tankwa Karoo, which is very dry, but compared to Black Rock’s it’s quite rocky. Color? It’s like a giant sepia photograph. So we don’t have whiteouts, we have beige-outs. got mountains as well. It’s extremely beautiful too. I suspect that the environment’s possibly a little bit harsher, although people argue with me. I think that’s an experiential thing. We don’t have as much powdery dust as you guys do, but obviously we also don’t have 80,000 people kicking up the dust, so the dust storms aren’t as bad, but the weather can be utterly biblical. It can really, really smash you. The wind is hard, the ground is hard; but at the same time, and that’s one of those mechanisms that just work, is that you have this incredible beauty and this incredible harshness which kind of rub up against you and defibrillate everything in you, and wake everything up. So…

ANDIE:

Sort of force your hand at creating community, don’t they? You have to connect with your neighbors to survive.

MONIQUE:

Exactly. It’s the old model. It works, but the beauty as well is also the other thing that works that we’re also very similar. We’ve copied Black Rock City town plan more or less, except it’s in the old days it was a little bit more organic, but we’ve just moved to our new piece of land, but then always responding because we don’t have this kind of classic blank canvas that you do. We’ve got kind of like little sand dunes and rocky patches and so on. We have the kind of semi-circle, and then it morphs a little bit this way and that way.

You’re going to get theme camps, you’re going to get artworks. It’s just more or less just artisanal really. And funny enough, you know, 50% of our participants are foreigners these days, and we call them time travelers because I think that they want to experience Burning Man in the 90s or the early 2000s, so they come to AfrikaBurn and they can cruise around and meet the same people three times in a night, and like, it’s a revolution. It’s a lot more villagey, you know?

One of the big differences was it took a little while for nudity to kind of entrench itself at AfrikaBurn, but three years in and it took hold and it was going well, and is going well. But yeah, the differences are tiny, and I think that these cultures and these things that we do, whether you’re at the “Gerlach Regional” or the South African Regional, it’s the same kind of model that is happening: the desert, the creativity, the beauty. Yeah, it’s just wonderful.

ANDIE:

Let’s bounce back to 2007 and when you started it, I know that you said it was bigger than you had anticipated right from the jump. How did you find, in a culture that hadn’t been to Burning Man yet necessarily because it was very far away, how did you find other leadership and how did you bring together that many people in the first place?

MONIQUE:

A couple of different reasons would be that, so there was a handful of people, it was myself, it was Paul Jorgenson, Robert Weinek, Mike Sas, and Lil Black, amongst other people who also left in. But we were the kind of primary founders at the time. And we had all been working in the kind of cultural realm in Cape Town / South Africa. So it was interesting because the first event, I think we had about probably 10 people who’d ever been to Burning Man, and that was amongst more or less 900 to 1000 people. We never quite know exactly how many people did actually come, no matter how many times I counted the ticket stubs.

I myself had been doing an event called the Mother City Queer Project, so I was very plugged into the kind of creative community in Cape Town. Robert ran galleries. Mike was involved in the trance scene, and Lil used to do these lovely, wonderful, weird gatherings and events. And so we kind of put all of our mailing lists together and started, I started doing quite a lot of public speaking, just putting the intention out there. We built a website, and we started this mailing list, and people just leapt at it.

And I think that’s possibly because there’s quite a very strong kind of camping and outdoor culture as well as the opportunity to go and make art in a beautiful place. And certainly in the creative groups that we were initially starting in, I think that there was quite a strong rebel renegade slash activist attitude, especially in being in South Africa, there’s that kind of jump in and do the thing. And I think also the context of South Africa being fairly lawless is fairly useful for starting Burns. In that way it was quite easy and everyone left in with hook line and sinker and socket sets and batteries and all the skills and all the wonderful everything and just leapt in, yeah.

It was such a surprise. I mean I myself thought that I’d… My own personal journey was that I’d just finished doing a thesis and I was like, “Oh, I want to do something distinctly non-academic.” I thought that I’d be busy for six months and now it’s been 16 years. So it was definitely a big surprise.

STUART:

Could you talk a little bit more about the lawlessness? I’m seeing a quote here from a story from Skift that you guys envisioned “a festival that would have an archetypal culture with its taproot in anarchy?” Boy, that sounds kind of familiar to me as an old Cacophonist, but very intentionally, the move to the desert was to get away from the authorities so they weren’t breathing down our necks. What was the story in the RSA?

MONIQUE:

The taproot of, I feel like all these burn movements, is an anarchy because it’s a questioning; it’s like, “Well, let’s go and define our own space,” and so we create that space. So the lawlessness that helped us certainly, and I mean when I say lawlessness, I’m talking that we have a far more kind of lax, or relaxed, kind of political structure around us.

We were also in this very interesting phase where we actually liked our government for the first time in a million years. It was quite weird to actually really think that we had a nice government because we’d all grown up hating our government, which is where that kind of lawless — our own internal lawlessness came from, where we were like “Uh huh, whatever the government says, if we don’t like it, actually fuck them.”

So for example, there was like event legislation, et cetera, but in the Northern Cape where we were starting this thing that actually was really difficult to define to the authorities, we just were able to do it. We started the event and we did de facto everything that would’ve been necessary to be able to get an event permit, but we actually never had an event permit for a very long time because there was no capacity in the Province in which we were to actually oversee what we were doing. We were always like, well, the government’s going to catch up with us at some point. And so we did do that, and now we are best of friends, us and the government.

ANDIE:

Is that advice that you would give to another regional to go that route before you go get your permits, or did it work out all right for you?

MONIQUE:

It wasn’t for lack of trying to get the permits. It was just a pragmatic kind of, “Okay, we are never going to get these permits, so we are just going to go ahead and make sure that they realize that we are extremely conscious and yes, we brave and renegade, but we are very resourceful and clever about how we go about these things.” And it’s that old understanding of anarchy as just rebellious mayhem which is not accurate, you know? YOU know!

STUART:

Self organization, right?

MONIQUE:

Which is exactly what it was. I think that’s why it really did help us at the time. It’s an interesting thing now to be in that state where, like I said, the taproot is in anarchy, but as global trends kind of affect Burns now, we have to be the fuzz. We are the kind of enforcers going in and going, “Okay, you can do this, you can’t do that” because we are trying to protect the culture or aspects of the culture that seem to be in peril or whatever.

And then also having to track everything you’re doing, and doing pie charts about how much investment happens in your Province, and all that kind of stuff, which is all very valuable stuff, but it’s quite, for me personally an uncomfortable, just a level of discomfort around actually having to pie chart up a Burn, you know?

ANDIE:

This all sounds very familiar, honestly.

MONIQUE:

I feel like I’m the little sister telling you guys what you already know.

ANDIE:

No, not so much.

STUART:

We have an awkward relationship with our government too. But is the move to private land, do you think, going to change that picture at all for you? Because we don’t have any options ahead of us for moving our event to private land, but you guys just were gifted some land that you can hold the event on, right?

MONIQUE:

Yeah. The first 13 years it was still private land, we just didn’t own it. We were renting it from private owners. It was a fantastic relationship. It really was. They helped us tremendously in the beginning, but we outgrew that site. Our desires around what other things to do with our movement were kind of feeling prohibited by the two month lease that we were occupying on that piece of land.

So we went through a very, very long process around the purchasing of land, or getting our own piece of land – financial feasibilities, all the motivations around supporting our creative crews and our contributors and being able to institute our idealistic desires around our organizational structure, you know, the composting of all the humanure and the circular economy systems around renewables and all that kind of stuff. Plus just suddenly we’ve got this space 365 days a year, that we can activate in different ways in these smaller gatherings. We do eco-trips, we have these smaller trips up there, which are extremely meaningful. And funnily enough, we attracted a lot of people who’ve never been to the Burn, you know because during Covid we were doing these tiny events and some of the most incredible alchemy happened in those spaces and has brought a new element into the actual burn.

ANDIE:

Tell us about some of those.

MONIQUE:

The piece of land that we got, well, all of that area has been ecologically damaged over quite a long time.

STUART:

From what? From overgrazing?

MONIQUE:

Overgrazing. So government policies around stocking sheep in a biome that was just inappropriate to do it in. It was called the pound for pound policy. A pound of wool was fetching a pound of money in price, and so they incentivized a lot of farmers to put up fences and overstock the sheep. Also the two main rivers coming into that Tankwa Basin were dammed for various reasons. Actually, as it turns out, those dams are pretty illegal. And so it used to be under production of wheat, 30,000 hectares, and now it’s just very, very empty desert land, which is great for our purposes.

But the opportunity of that, is that it’s the opportunity to do ecological restoration events where we gather and we are trying different… especially with the Burner attitude of inventiveness and ingenuity, et cetera. So there’s a kind of master plan around slowly trying to turn that place around ecologically with the good intent of our community, and grow the community, and hopefully those kinds of things will move out horizontally from the activities that we are doing.

Then we also did another one called Rise which was gathering women specifically on the land. And we did a whole lot of healing work and workshops and art workshops, et cetera, which was also very fertile ground.

So we’ve had all these really small gatherings, which have been amazing. And really that’s one of the nicest opportunities from having this new piece of land now.

The thing is that we’ve got this 10,000 hectares and it’s extremely beautiful and there’s a lot of archeological history there. There’s a couple of middens that are being excavated by archeologists. It’s just this deeper engagement with the land that we are doing this really important thing on. It’s a very meaningful thing actually. I love it to bits.

And it was a lovely gift because after we tried all the financial feasibility and someone came up to us at the Burn and said, “Look, I hear you looking for land and I’m going to buy it for you.” Yeah, that was a lovely gift.

ANDIE:

That is a lovely gift.

STUART:

That makes me want to know more about the traditional inhabitants of that land, I believe it’s the San people, and your relationship with that group.

MONIQUE:

And that would cover pretty much most of South Africa, is the San people because they’re the first people.

STUART:

I see.

MONIQUE:

But yes we’ve had a fairly long relationship with San people. Not the San people because it’s not a homogenized group. There are various kinds of San groupings around the country and we’ve kind of brought them together to actually attend the Burn. They’ve been running a San camp for about eight years, maybe a little bit longer. We’ve had quite a deep engagement with them around that. And I think as we are recovering organizationally from huge financial loss and loss of capacity in our organization from Covid, one of the main aims is to expand that side as we get traction again.

The first time we went out there all as a group, after we now had our piece of property, the San group came and joined us. It was quite amazing, and they did a lot of ceremony, and they’re doing a lot of ceremony, and they come to the Burn and they have a San camp. So that aspect is getting a lot of resources.

STUART:

I ask because I think that’s another area of similarity and that we are still trying to figure out how to have a great relationship with the Numu people in the area of the Black Rock Desert. There’s so many areas where I think we do have a capacity to learn from our little sibling as you put it.

Related to that is in sustainability. I understand you guys have a lot of big sustainability initiatives. We’re desperately trying to shift over our gigantic carbon footprint into a smaller carbon footprint. What’s happening in AfrikaBurn on that front?

MONIQUE:

Well, I mean, look, the thing about us is because we are smaller, obviously our footprint is smaller, but we do use entirely less power than you do. I was so amazed at Black Rock City this year that on the city block that I was living in the org camping, that two generators were used for that block, one of which is what we use to power the entire operational side of AfrikaBurn!

STUART:

Good to know.

MONIQUE:

But we’re under-resourced and we’ve been composting the humaneure, I mean all the sewage, for a good couple of years now, and we give that out to the local farmers. But actually now that we’ve got our own eco restoration projects going, we are going to be utilizing it for our projects on the actual land, unless someone really needs it for their trees or whatever. That’s very useful.

But also not only that it’s useful for us in terms of our operations around the actual event, but it’s useful because when Cape Town nearly ran out of water, we’d invented these toilets for our event, and the city of Cape Town came to us and they were like, “Okay, we need you to roll out those toilets because they’re exactly what we need in this crisis.”

ANDIE:

Amazing.

MONIQUE:

That’s one of the models about the experiment that we do, is that there are ideas lying around and when shit hits the fan, excuse the pun, there are ideas available to utilize. That’s just one of those fertile things about the space that we create, and which operates so beautifully.

We’ve got more plans than we have rollout because of lack of capacity and money at the moment. But that’s definitely starting to turn. But, yeah, being able to control our own water and to put in our renewable energy sources, and do the humanuring and all of our waste management as well is really useful. In fact, we are getting a gasifier soon; to utilize the hard plastics to turn into fuel. So yeah, all those experimental things are starting to coagulate into like a more cohesively working unit.

ANDIE:

You have a lot to teach us on this.

MONIQUE:

Well, I think you guys are doing amazing work too. I mean your toilets were amazing.

STUART:

The EcoZoics.

MONIQUE:

The composting toilets.

ANDIE:

Yes. And I understand that of those big generators in those staff areas and other support systems for such a big city like ours, I believe the number is 64 generators that we were able to replace with solar this year and the initiatives are moving forward. We experienced the same capacity issues, and coming back from the years that we’ve all had off of doing our events gave us some time to focus on those things and now they’re really kind of rolling out into our events as we get to do them again.

MONIQUE:

Yeah, it’s like turning a tanker in the ocean. It takes energy to kind of overcome that inertia and turn the tanker. But yeah, one thing that always amazes me about America is how much people love air-con.

STUART:

Oh my, yes.

MONIQUE:

It’s astounding. air-con everywhere. Really?

STUART:

I think it’s more like we’re turning one of those gigantic old big-finned Cadillacs from the 1950s that got two miles to the gallon, which was absolutely the right thing to drive out there back in 1867 when we started this thing.

What’s the Dung Beetle Project?

MONIQUE:

The Dung Beetle Project. Whenever I read exactly how it operates, I understand it, but I can never quite repeat it out again. Google the Dung Beetle Project. Basically they’re creating these generators that convert plastics into fuel through a gasifying process. They started at AfrikaBurn by doing a dance floor entirely powered by plastics. And they’ve done that five times, I think. Great music as well, great environment, and then they created this big kind of dung beetle sculpture around the generator. So it looks really beautiful. It’s just nice to be able to convert all the things into power: the wind, the sun, the shitty plastics.

STUART:

Amazing. Well, obviously Leaving No Trace is one of the principles that’s been under sort of historical pressure, and we’re all being forced to look at that differently in terms of global warming and all of the other things that are happening in the world.

Radical Inclusion is probably the other one that I know we’re having some issues with here and desperately trying to get caught up in terms of addressing systemic racism, which I understand, I just learned this today, I was stunned to find that y’all did a bit of a rewrite to the principle of Radical Inclusion.

MONIQUE:

Yeah, I mean, look, the Radical Inclusion principle has always been personally a worm in my ear because in the South African context, it’s almost glib. It’s a beautiful piece of writing. All of the principles are beautiful pieces of writing, but particularly in the South African context. And I will always say this: Racism and systemic injustice exists everywhere, but, it’s in such a kind of concentrated fashion in South Africa. And for me, kind of doing public talks where I was talking about the principles and explaining what this weird animal is that we do — that we are — and whenever I got to the Radical Inclusion principles, there was this discomfort in me because literally saying here, “anyone can be part of this” is not true. And so that’s why we kind of redrafted it and then we sent it to Burning Man IP and they said it’s still got the essence, so they endorsed it. But yeah, it sits far more comfortably for me now I have to say. And I think it’s more accurate.

STUART:

Yeah, actually, lemme read it. “Everyone should be able to be a part of AfrikaBurn. As an intentional community committed to inventing the world anew, we actively pursue mechanisms to address imbalances and overcome barriers to participation, especially in light of past, current, and systemic injustice. We welcome and respect the stranger. Anyone can belong.” That’s really, that’s quite well written, and inspiring.

MONIQUE:

These are the things that we have to look, and I mean, I like to talk about Burns, not Burning Man or AfrikaBurn or that Burn or whatever.

STUART:

Of course.

MONIQUE:

They’re Burns. These are all issues that arise wherever we go actually. And inclusion is such a massive one that either photo negative of the demographics of the country in South Africa is a thing. Those kinds of things can be systematically turned around if there is will and resources behind it. Certainly at Burning Man, I think you guys are also doing a great job as well. So many kind of policy things that we’ve done around that, I’m not even sure that anyone ever notices that we’ve changed the Radical Inclusion principle, but at least it’s changed.

STUART:

Well, I noticed, because that’s my job, I had to do a lot of lobbying too. The only change that we’ve made on our end is to the principle of Radical Self-Reliance. There was some gender binary language in there, “his or her inner resources,” we changed that to “their.”

MONIQUE:

Okay. Oh, that’s interesting.

STUART:

Larry Harvey put his feet down, and said “Don’t ever change a single word.” And thankfully we’ve already started breaking that rule. So I’m just fascinated to see that you’ve done that because we do have that in common, don’t we?

MONIQUE:

Absolutely.

STUART:

South Africa is a poster child with apartheid for systemic racism, but how fundamentally different is that? You really look at a whole history of colonialism, it’s interesting to me how many of the largest burns take place in countries that used to be English colonies. Also related to that is: At least in the United States, we can’t disentangle issues of race with issues of class and money. I know that South Africa overall is an extremely poor country. So, how do you make an event accessible to someone who’s living barely at a subsistence level?

MONIQUE:

I actually have a discomfort around the fact that the race and class thing get dovetailed. Basically when we first started all of our work on this, which was very close to the beginning, but we’ve now had a lot more resources to actually channel at looking at this problem and actually trying to invent the world anew. So we just looking at the barriers to entry basically. And very clearly in the South African case, it’s very, very often 98% is about money. Race and class are still radically divided along those lines. The correlation is almost a hundred percent. So looking at the barriers to entry’s financials, so we have tickets that are available at a tenth of the actual price, and then we have access and welfare grants. Our creative grant process is also skewed; the scoring goes much higher if you’ve got an outreach aspect to your application. And we’ll always favor those as well. And internally, we were doing work in the organization around employment policies and we were doing a hell of a lot of workshops, et cetera. There’s always more work to do.

So once you’ve overcome the barrier to entry, ie: getting to the actual burn, what’s the experience like there? Do you feel like you’ve got agency? And sure, a lot of people have a terrible fucking time at the Burn, you know? It’s not like you automatically, just because you are in, you’re going to have agency or just because you’re white, you’re going to have agency or whatever. This is a sore point.

The other thing is that for the foreseeable future, people of color are still going to be in the minority. Especially in the South African cas, that’s not ideal because we’ve got 10% white people and 90% people of color in the country, so that’s just weird. Looking at those kinds of dynamics and creating safe places, spaces and having racism response protocol for our organization, and even banning protocols around that, which is us being the fuzz again, but it’s the right thing to do.

STUART:

To kick somebody out of Tankwa Town.

ANDIE:

Right.

MONIQUE:

It was amazing because, I mean, I’ve been watching the kind of Black Burner Project and listening to the podcasts and the chats on Instagram, et cetera, and it was a really beautiful moment to see that party that happened at the artwork where it was predominantly people of color.

ANDIE:

BLACK! Asé. There was a gathering at BLACK! Asé.

MONIQUE:

Yeah. It was an experience of that kind of dynamic where it’s actually, there were more people of color than any white people. And I was just like, yes, that’s progress. That’s amazing.

ANDIE:

Yes. And I think you touched on this a little bit a while ago, that it’s not enough to say that everybody can come and is welcome. Sometimes you have to project the invitation and let people know that they will be a part of a community that invites them specifically and makes them safe where they are.

MONIQUE:

Exactly.

ANDIE:

Because it doesn’t always feel that way when you look at images from an event, and it’s mostly white faces; let’s be real.

MONIQUE:

There are new things. There’s gonna be: how do we not generalize a black population? There’s so many aspects to it. There’s a million pitfalls. And just for the record, I’m very aware that I’m a white person saying this. I’ll just leave it at that.

ANDIE:

It’s a big fish to fry for sure.

MONIQUE:

Especially when one thinks of where burns are. Okay, so Burning Man’s nearly, what is it, 30 years old now?

STUART:

35, 36, something.

MONIQUE:

Looking at the evolution of it and other — you know we’re 16 years old. The challenges to our cultures, as I perceive them, are very often global trends. But there’s also a bit of an existential crisis in my mind around “What is the relevance?” Burns are so well mapped now. There’s a highway called Burning Man, AfrikaBurn, whatever, and that you’re going to buy some kit, and you’re gonna get a bicycle and you’re going to to decorate, and you’re going to do this and you see lovely things and da da da, da, all that kind of stuff. That’s the well mapped route.

And so the invitation to move off that highway, the other taproot of this, the trickster taproot is the crossroad, which is “Uh-uh, come into the jungle with me and let’s go and meander around this vine and work out a different way.”

And so for me, the relevance of the Burns is around going: Okay, if this is experimental, then let’s deal with systemic issues like sustainability, and race issues, or representivity, or all those kinds of things — without being political about it because actually politics is a bullshit fucking story. Excuse my language. People should just be living in service of other people, which is what the Burn does. And for a beautiful whole, I know it sounds very hippie, but that is also another taproot in it.

STUART:

Well, earlier you used the phrase ‘creating a new world’’ which sounds a little bit high blown, but to me that’s very specific because I get asked all the time why, particularly, our organization, Burning Man Project, is not more politically active. And I just keep coming around to the fact that we’re not here to change the existing system. We’re here to create a new one out of the bones of the old one, right? Alongside of it. As long as we continue to do that and keep thinking about change and innovation, and moving forward, and building things the way we want them to be, we’re unstoppable. But like you said, the more accurate the map gets, the less people are to engage with the actual territory. So overall, do you really think we’re making an impact? Why do you do this? Why have you devoted the last 16 years of your life so much of that time, to moving this culture forward?

MONIQUE:

My academic training is environmental science. When you study that, it’s very easy to become anesthetized as to what the fuck to do and where to start. And you feel like you’re going to be in a fight because you’re fighting for rights, you’re fighting for this, you’re fighting for everything. I’d just done my thesis and I was working on land reform, which is very close to my heart too. But I grew up in a very creative household. My parents were in the theater. I grew up in apartheid where that trickster energy was like, if you are doing theater, you can poke at the establishment and you could say shit that no one else is, other people are getting thrown into jail for, et cetera. I mean, a lot of my father’s players were shut down with the cops anyway, but regardless, you could still say it and get away with it.

And so that kind of energy and play and fun are such important things. And then I’d been working on this event called the Mother City Queer Project where we were celebrating our new constitution and just so excited about all the non-s, you know, non-racism, non-ageism, non-sexism and all that stuff. We couldn’t believe the feeling when the new government came in. It was so amazing. So I’d been doing that for 10 years, which was distinctly celebratory of our new constitution, in a very fun and irreverent and arty way.

So when I went to Burning Man, I was like, oh, okay, well there: fun and play are the vector for change here. Because fundamentally all these changes that we are talking about, and I don’t mind if your burn is just about coming and having an immersive dance experience, I don’t mind. But for me, it’s about changing the world.

And you do that by accessing aspects of yourself that go dormant in the default world, because aspects of the default world are not ideal, a lot of them. But the fun and play vector was such an attractor rather than like fight with picketing and that kind of stuff. For me, it was around potentiality around paradigm shifting stuff and having shit tons of fun in the process and meeting the best humans that exist. It’s just been such a rollicking adventure.

The shadow side of that is that when you are informed by passion, it quite often can lead to exploitation. And so overwork is a problem which is why I’m on a sabbatical. After 16 years, I’m having a break. But that’s the personal thing for me, is that catalytic potential for much bigger potential change. For other people it’s different, and there’s no judgment related to that at all. It’s just that that’s it for me. And I still am exhausted by the sheer potentiality all the time.

ANDIE:

So not everybody’s going to go camp out in any desert and be affected by this. There must be ways that play and fun manifests in cultural engagement with your community year round. Can you tell us about any of those?

MONIQUE:

We started a thing called Streetopia. Tankwa Town is the name of our little city at AfrikaBurn. I was standing in Tankwa Town one day, I was just having a brief moment of waking up, and I was like, “What is it that is so lovely about this town? Why is it?” I was just being analytical. And then I was like, “Oh, well it’s a town where the creative projects ratio to city infrastructure ratio is completely inverted compared to a normal town. So what we wanted to do with Streetopia was to invert that ratio for a day. So in the village green and on the streets and everything, you just flood the place with art and created projects, et cetera. And it really turns a place around.

And we did it in Observatory, which is where I live, but this is basically where we almost started AfrikaBurn because all the first public meetings were here. And it’s a little bit of an old lefty liberal community. All the homeless people come live here because they get fed so well and get given tents and stuff. But it’s a lovely community and it’s got a lovely little kind of Bohemian street. So we just went around to all the shops and — non Burners — and we convinced them to, this is the idea, this is why we want to do it. We closed the street down. And it’s been quite amazing how Streetopia has been almost such a segue for people coming to the Burn. And interestingly enough people of color too, because they wouldn’t necessarily go all the way to the desert to this “white event.” I’m doing air… what do you call them?

ANDIE:

Quotes.

STUART:

Air quotes.

MONIQUE:

Air quotes. But they come to Streetopia and experience a little bit of that feeling. And then the other part of the experiment is also there was the Streetopia Legacy Project where we were all just sponsoring lighting projects and murals and all that kind of stuff. And it really has taken traction. I mean, we don’t really have to do much anymore. They do it themselves.

ANDIE:

Because people like to participate and have fun.

MONIQUE:

Yeah. We’ve got a thing called Hammer School, which is all of our fantastic D.P.W. members who teach people how to weld or use power tools.

ANDIE:

I love that name. That’s great. Hammer School.

MONIQUE:

Yeah. Well, our D.P.W. Council is called the Hammer Council. So Hammer School. So the metal work department will do a welding workshop with people who just want to learn. And very often non-Burners come and they do that. That’s why I keep saying the sky’s the limit. You can just do lovely things with a lot of lovely people.

ANDIE:

And that’s one of the, what would you call it, one of your mottos there; it’s your 11th principle: Each one teach one.

MONIQUE:

Yeah, man. Each one teach one. How often people say it’s their favorite, but we actually, we invented that one on the back of our rapid growth. I mean, it’s important, but we were growing so fast that there was this tendency for people to not necessarily be properly acculturated. That’s also why we started limiting that. We were like that thing of not being victims of our own success. We wanted to communicate that this is not a centralized org. One has to educate each other. It’s not a centralized mechanism. So that was the one that we came up with. Yeah.

ANDIE:

I like that.

MONIQUE:

As you were talking earlier, Stuart, about the limitations of Leave No Trace. In terms of the kind of environmental imperative. We’ve been toying with the idea of radical regeneration. But then actually I just like the idea of just generation, like radical generation of everything. We don’t have to just re-. Sustainability is an old word. It’s like, we so far have gone beyond sustainable anything, that we actually have to generate, not regenerate. We have to do more. But anyway, that one’s boiling in the back.

STUART:

Be careful. I think there’s a soda company slogan in there. Doesn’t Pepsi have something about the radical generation? Yeah, that’s right. We thought of it first.

ANDIE:

Oh yeah. That was a campaign in the early nineties, perhaps. It’s ours now. It’s theirs now. It was extreme.

STUART:

So what’s this year look like? We’re coming up on AfrikaBurn season, which by the way is, I think the only reason we could get you in early February is that you are taking a sabbatical this year.

MONIQUE:

Indeed.

STUART:

It’s the end of April? Are tickets already all gone or?

MONIQUE:

Yeah. They usually sell out in minutes like you guys.

STUART:

Well, for people who want to put it in their calendar for next year, when should they start looking for AfrikaBurn tickets?

MONIQUE:

They usually go on sale in September. Early September. But I mean, look, life happens and there’s always loads of resales. If you still want to come to AfrikaBurn this year, go onto Quicket and just plug into the resales. A lot of tickets do come up just before the event.

STUART:

What’s your ticket reseller called?

MONIQUE:

Quicket.

STUART:

Quicket.

ANDIE:

Quicket.

MONIQUE:

Yes.

STUART:

And I imagine you’re going to be there just drinking cocktails and sitting in the shade?

MONIQUE:

No.

STUART:

Okay. Be careful. The first time I did it, I was bored, silly and was constantly looking for something to do. But that was just me.

MONIQUE:

It’s going to be a very interesting Burn for me. I think I’m going to my first AfrikaBurn.

STUART:

Yeah.

ANDIE:

Hard same. Yeah. I found myself wandering back down to Media Mecca like, ah, okay, this is where I’m supposed to be.

STUART:

But you should have the experience. If you can team up with a first timer, that’s always good.

MONIQUE:

Oh, that’s a good idea. I am a first timer, but I think what I might do, I thought of actually doing a sculpture, because I love building structures, but I think I’ve left it too late. I might just join a creative crew and then just take off when I want to because the responsibility’s not all mine.

ANDIE:

Nice.

STUART:

That sounds heavenly. Any chance we’ll see you out in Black Rock City at the end of this year?

MONIQUE:

There’s usually about four years between me coming to Black Rock City, particularly because of the exchange rate. But I think I would like to. I do love coming and rollicking with you buggers.

STUART:

Well, next time if you see me on the playa, please don’t walk by. Come on over and say hello.

MONIQUE:

It was at a meeting that I saw you, which is why I didn’t approach you because someone else was speaking.

STUART:

Yeah. Meeting Man, the bane of our existence.

MONIQUE:

Yeah, totally.

STUART:

Meeting Man and Spreadsheet Man ate my liver.

ANDIE:

Well, I think this has been enlightening. Is there anything we didn’t ask you about that you want to mention?

MONIQUE:

I think that’s it.

STUART:

Felt like a good talk to me.

MONIQUE:

Good.

STUART:

Well, thank you so much for joining us. Our guest today, once again, was Monique Schiess from AfrikaBurn. It’s great to see you.

ANDIE:

Monique, thank you.

MONIQUE:

Thank you so much. Caio.

ANDIE:

And that’s a wrap and a show here at Burning Man LIVE, a production of the Philosophical Center of Burning Man Project. I have been your host, Andie Grace. And I will be Andie Grace again tomorrow.

Meanwhile, if you like what you hear, we do encourage you to visit us and donate to Burning Man Project donate.burningman.org.

And my thanks to those who helped make this episode possible, including Michael Vav, Stuart Mangrum, kbot, DJ Toil, and you dear listener, for loaning us your ears. We’ll talk to you next time.

Thanks, Larry.

more

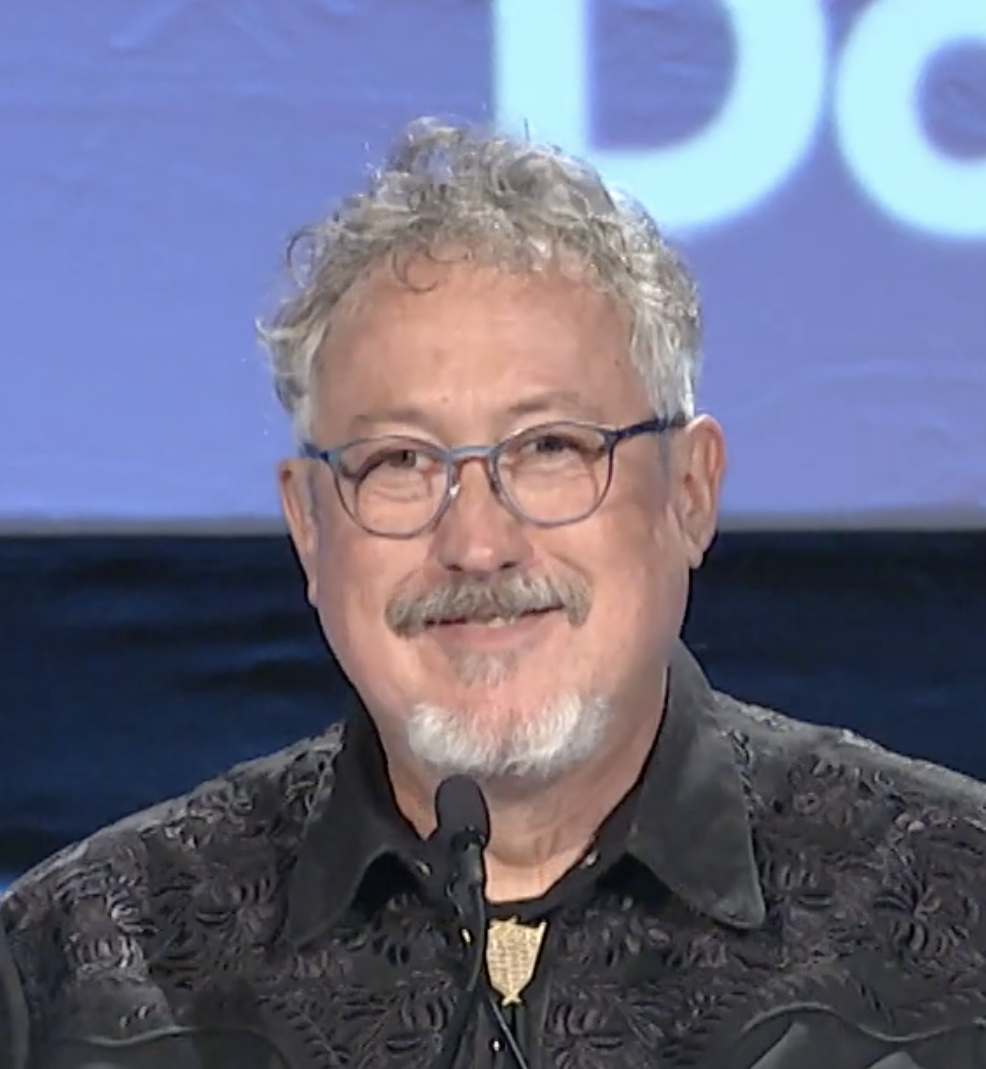

Andie Grace

Andie Grace Monique Schiess

Monique Schiess Stuart Mangrum

Stuart Mangrum