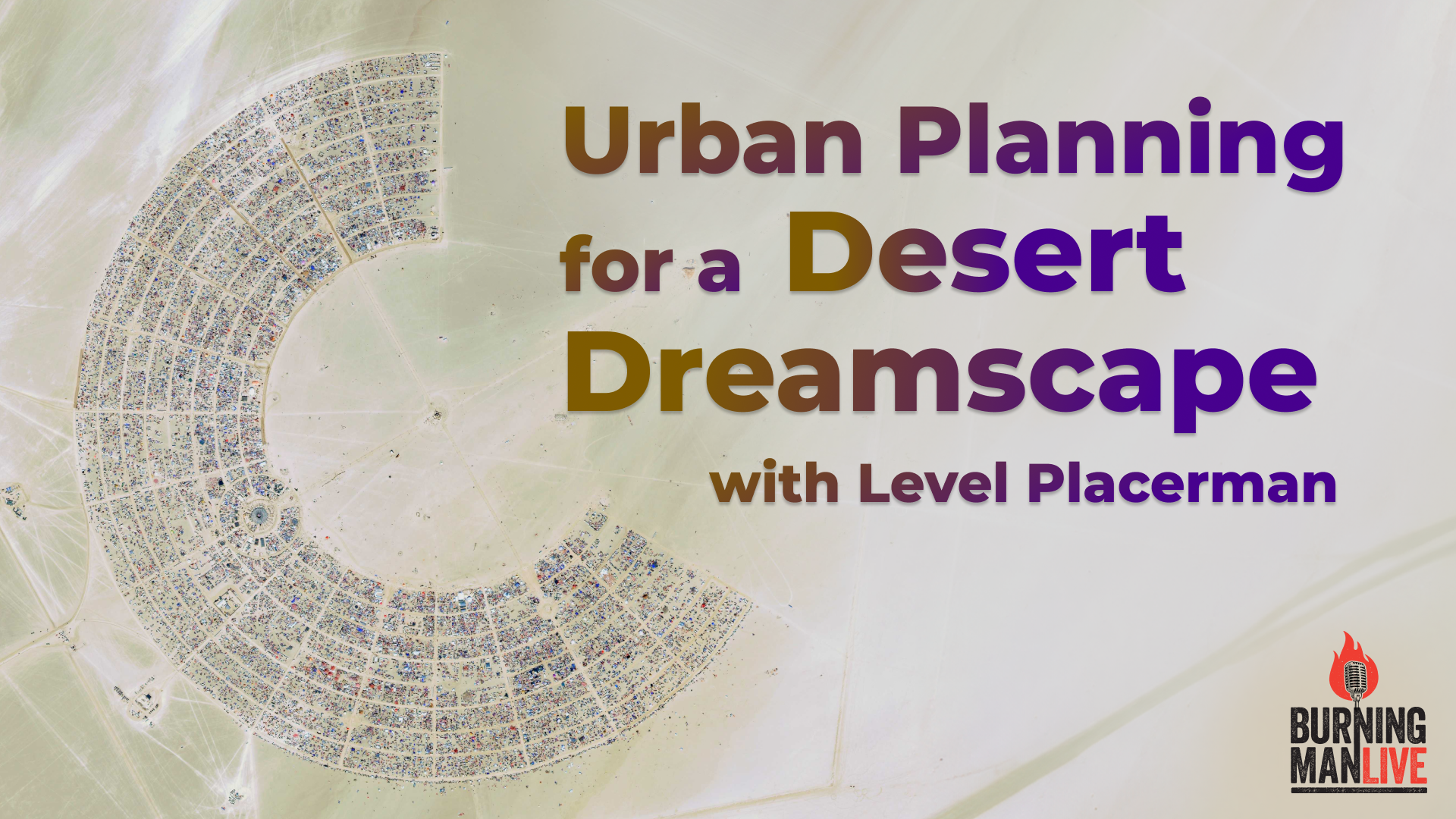

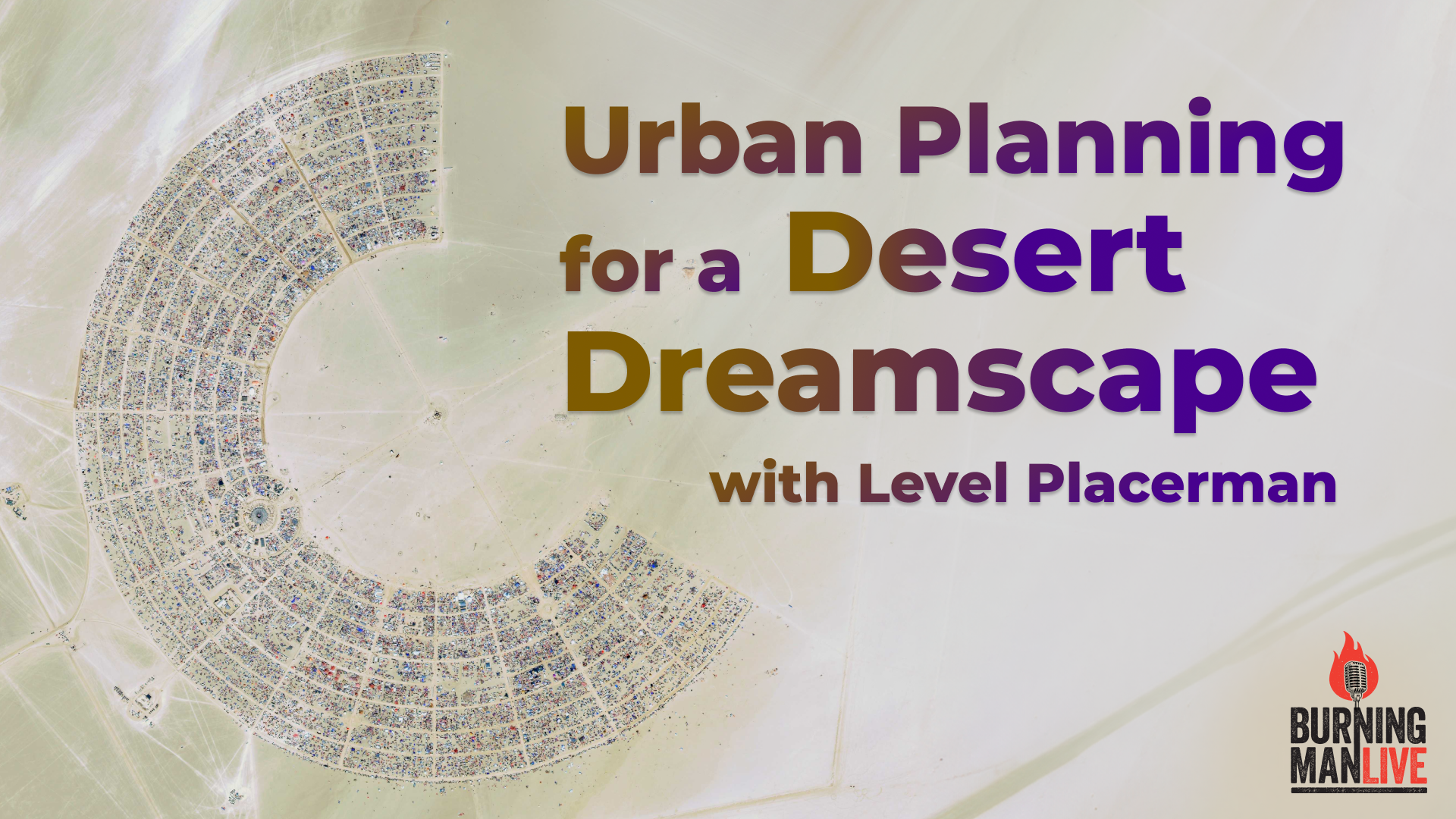

Urban Planning for a Desert Dreamscape

Black Rock City is a temporary metropolis of 80,000 people who inhabit 1,600 theme camps and support camps. That means nine out of 10 participants’ plans are coordinated by the Placement team — a handful of dedicated staff who decide which camps go where, and why. This year-round process is an art and a science that takes many factors into consideration — from city dynamics, to campers’ Radical Self-expressions.

As Burning Man Project’s Associate Director of City Planning, Bryant Tan manages the Placement team, and oversees the city’s annual planning and placement process. Naturally, questions about Burning Man lead to more questions.

- How do we place like-minded folks together for harmony, not monotony?

- How are resources shared between camps in this new era?

- Can you tell me how to get to Center Camp Plaza?

- What rules cultivate a spirit of lawlessness?

- Is bigger actually better?

Let’s go behind the scenes, under the clipboard, and beyond the map, exploring opportunities and obligations to iterate in this experimental city. It’s a unique test case for urban planners and any humans who live in semi-civilized situations.

BurningMan.org: Placement Team: Level

BurningMan.org: Placement Process

HUBS: Humans Uniting for Better Sustainability

PEERS: Placement’s Exploration and Engagement Research Squad

Transcript

LEVEL:

Burning Man started out of disorganization, and just people showing up to the desert and not needing a street grid, not needing anything, and there’s a beauty to that.

And as more people show up over time and more, sort of, challenges occur with more people showing up, you start needing to create systems and bureaucracies.

STUART:

The Burning Man movement has over a hundred official events around the world, all year round. Different parts of the globe. But the original, the mothership, our capital city, if you will, of our strange imaginary nation, is a pop-up city we call BRC, Black Rock City, out in the wilds of the Nevada desert.

While it’s temporary, it is still, in just about every aspect, a real American city. It’s about the same size population-wise as Santa Fe, New Mexico, and it’s got all the things you’d expect to see in a city of that size: a hospital, post office, an airport, a fire department, all that.

And while there’s no Mayor or City Hall, there are of course some of the city’s service functions that any urban dweller would recognize at a glance. We have a DPW, and we have a DMV. And while there’s no office of plans and permits for the tens of thousands of people who live in theme camps, or what we call collectively placed camps, pre-arranged through an application process, for all of those people there is the Placement Team.

I’m Stuart Mangrum, and in this episode we’re gonna shine a little light on what for some people is well a complicated sometimes confusing process of getting placed, as they say in Black Rock City.

My guest today, a conversation I’ve been looking forward to have for a long time, is Burning Man Project’s Associate Director of City Planning, also known as Placement Manager, also known as Level Placerman. Shall I include your government name as well?

LEVEL:

Yeah, yeah, sure.

STUART:

And sometimes known as Bryant Tan. Welcome, Level. How you doing?

LEVEL:

I’m doing great. I’m happy to be here. I always have a lot to say, so looking forward to it. Yeah.

STUART:

OK, great. My first question, I’m going to ask a silly question: What is it with all the placers having a first name and then Placer? We’ve got Machine Placer, we’ve got Hogwarts Placer. Is it like the Ramones? Did everybody just decide to take Placer as their last name?

LEVEL:

There’s a whole ritual and initiation to get that last name as Placer that we go through, but it’s just a moniker, and quite frankly, we also try to remain sometimes anonymous in the community because, especially in social media, given the role that we play, we don’t necessarily want people always knowing exactly who we are, and so, yeah. Like Rangers are called, you know, Ranger Saturn or whatever their names are, and so we’re Placer.

STUART:

I imagine that members of your team have to tell people no on a fairly regular basis, or give people news that they don’t necessarily want to hear. So we’ll go a little bit deeper into that. But first, I just want to talk about urban planning. This was not something we ever imagined that we would need in Black Rock City. In fact, when we first decided to put up a city limit sign, it was half a joke. And now, these, what? 35 years later we have you on our staff who actually has a Master’s in Urban Planning from MIT.

First question: Is it even really a city? Or are we still just sort of patting ourselves on the back and calling it something it’s not? How is it like or unlike other cities of say, I just looked this up, Camden, New Jersey, it’s about the same size as Black Rock City?

LEVEL:

Yeah. You know, I think that there are a lot of parallels to what cities have to deal with. Cities are just gatherings of lots of people. They happen to be semi-permanent gatherings, right? Buildings are built for hundreds of years in cities, and in Black Rock City, they’re built for a couple of weeks. Some of the conditions are different, but a lot of the dynamics are the same.

We’re talking about: How do you bring people together? How do you have them live, and cohabitate together in a manner that they can coexist and respect each other?

How do we get certain parts of cities to activate at different times of day?

Most planners are actually dealing with an existing built environment, and trying to figure out what do you do with a parking lot or what do you do with a neighborhood that might be a little bit more disenfranchised? We don’t have to deal with that in Black Rock City, but we do get to deal with a blank slate, which is really, makes the job a lot more interesting in some ways and a lot more challenging in other ways because the temporality of it requires a different way to think about it.

And at the end of the day, I think urban planners have visions for what communities and people and space should look like, but they don’t always get that blank slate to work with, and so, you know, as a planner myself, I feel really lucky to be able to rethink this every year.

STUART:

Now let’s be fair, it’s not really a blank slate. I mean, it is, we leave no trace every year, but there’s so much history there, and the expectations of a community, that things will have some sort of continuity, be like they used to be. I remember when the first year we had placement, Harley Dubois, who, she was a firefighter in real life, in her day job, she started the whole process just around the same time that we started laying out the city in an actual city grid and thinking about our relative positions to each other. But how does that history, I mean, there are camps that have been placed for 30 years now. How does that history impact your job?

LEVEL:

We come at it with a lot of deep respect for what was, and also with a mind towards the future too and how do we both iterate and innovate, respect the people that came before us that are still around, and as well as try new things as things develop both in Black Rock City and in the world. When you think about space, when you think about community, when you think about home, which I think we all do, right? We have feelings about it and associations about it and ideas about it. You know, you walk around or ride your bike around or drive around your own town and you have a sense of like, Hey, that corner could work better if it was this, or I really would love to see some art there. And I’d love to see that shuttered storefront turn into something really wonderful, right? We all experience the city just as people. And so you don’t have to have tons of history with it to have ideas and have perspective.

I think what’s useful and different about Black Rock City is because we can iterate. My hope is that with camps that have been around for a long time, they are used to the shuffle that Placement puts them through and really take on the idea that they are anchors in this community both as physical spaces and as cultural spaces so that people can turn to them to really understand what does it mean to be a Burner? How do you do it in Black Rock City? How do you leave no trace? And it’s always wonderful when we get long-time camps that are like, “Hey, move me somewhere new because I wanna expose what I know and what I do to a different part of town.” And more often than not, there are many camps that are long-time camps that want to do that.

STUART:

And people who are surprisingly change-resistant in a world that’s constantly changing and an environment that changes every year.

Now you mention the Esplanade, and if you’re not familiar with Black Rock City, dear listener, that is the main frontage, it’s our main drag, the frontage road that faces out towards the Man and the artwork. Now placement used to just be about that, really. It was about Center Camp and Esplanade, the rest of it was “go seek your claim,” like the Sooners in their wagons racing across Oklahoma. Nowadays, a very large percentage of the city is actually placed before the gates open. Why so many? And what is that percentage? Is there any free land left anywhere that people can camp in without going through the process of placement?

LEVEL:

We’re at a crucial point in the city of thinking about how much open camping makes sense, because over the years, we’ve sort of gobbled up more and more space for placed camps, so that you define the boundaries, you get told by Placement where you are. Even when I started volunteering for the team in 2014, we were placing maybe half of the city. This past year, we placed roughly 90 to 92% of the city.

STUART:

Wow.

LEVEL:

That’s the significant portion. And the community feels it, you know, there are still long time Burners that go and say, “Hey, I used to have this spot that I loved and no one ever cared to even state claim on it on G street, and now it’s just all placed theme camps.” There’s some tension there.

The incentive for people to get placed is that they have access to tickets, they obviously have access to space, access to come to the event early to build their things; and so because of ticket scarcity, it’s caused more and more groups to, even if they were really happy as long-time open campers, they’re realizing that the competition to just get tickets is so strong that bringing a placed camp and a registered camp is the way to do it.

We’re at a point where we’re saying we want to communicate more with community. We can’t just continue to grow. The last handful of years, we’ve seen anywhere from like 100 and 150 new camps join the fold, without necessarily the same number taking a year off or deciding to retire from the event.

And so we have had population limits for about a decade now, and now we’re facing also space limitations, and we can’t just keep adding streets. We just can’t keep growing the pot. The pot is full.

I feel like we’re at this point trying to keep the placed camp margins at about 90%. And we may need to dial it back. Again, I think it’s sort of like recognizing the culture that is brought both by those folks looking for a spot in Oklahoma, like you were mentioning earlier, and want just more of a free ability to do that rather than the constructs of a process: “Fill out these forms. Go through these hoops.” People just want some freedom because that’s kind of the origin of Burning Man.

STUART:

Yeah, that’s an interesting boomtown dilemma. You gotta make room for the new people. And it’s hard to imagine in that great endless sky, in that vast space, running out of room. But yeah, the permit only covers so much land. You can’t just keep adding streets. It creates logistical nightmares. But how do we keep that door open? I think a lot about succession planning as well. I think about who’s gonna be running the theme camp that I love 10 or 15 years from now, and I imagine it’s not someone who’s doing it right now. So having that door open and the ability to get in is pretty crucial.

How do we persuade people who are already doing it, or have been doing it a long time, to back off a little bit, pass the reins, do some succession planning? That’s a tough thing. I know that particularly because they’ve gotten used to the steady diet of tickets, and access, and all that, it’s a routine that they don’t want to give up, right? So how do we persuade people to give them ways to make a graceful exit or succession?

LEVEL:

Yeah, I don’t know that I have the perfect answer for that. There’s this impression from the placed camp community, from theme camps, that they have to go bigger and bigger every year, that placement expects more of them in order for them to just stay afloat. I just wanna say really clearly, that is not true. You know, camps can come back as the same thing, they can come back as smaller things, they can remain a little mom & pop, and we’re happy to see that. We actually love seeing small things, unique things, creative things that a small group of people do. I think that reassurance to people helps give them security to say, okay, actually, yeah, I was under this impression maybe because of the default world and with capitalism and all that, it’s all about more GDP and more growth and all that. We don’t apply that standard in Placement.

And also helping people understand that you’re not going to be seen as a deserter for taking a year off. We do encourage people to take some time off. I hope that with the pandemic sort of forced time off, that gave people some perspective that it’s okay to take a break. You know, it actually, people can feel refreshed and rejuvenated to come back, maybe even with more creativity and more passion after that break. We have to figure out how to shift the culture to see that, to normalize taking breaks, to normalize downsizing, like, “Hey, actually I’ve been in this line and I recognize that maybe I should step out of the line for a year so that someone else can come in line.”

I think that is the challenge ahead. And I wish I knew the exact answer for that. I wasn’t around during this time, but I think that when the Regional Network grew, it was about recognizing that Black Rock City could not hold all the interest of people that want to do this thing. And so, I wonder if now that we’re also hitting this limit with placement, could people be reinvigorated to have even more Regional Events and Regional things happen, that take the place of their spot in Black Rock City for a year?

So, I’m excited to see what could happen, but I think part of that for me is about sharing the data, sharing these dynamics, just starting to say, hey, actually there are limits, and what can we do together? We’re open for ideas.

STUART:

Well, having helped organize quite a few camps myself over the years, I will say there are kind of social limits on how effectively you can get a group of people working together. Certainly, I think when you hit your Dunbar number, which is, as I understand it, the maximum number of people that you can kind of know and remember their names, but which is like 100. I would say personally, it’s more like 40 or 50 with the camps that I’ve been associated with that are the most successful. So what happens if we tell that 500-person camp to become ten 50-person camps?

LEVEL:

Yeah, I think that’s part of the effort too. Dunbar, Robin Dunbar was a psychologist that studied social relationships. His number was 150, where it was about how many true connections could you have with people to have relationships with? And if you sort of think about your own world and your own life on an everyday basis, if you’ve ever planned a party or a dinner or anything, keeping it small makes it a lot easier, builds stronger connections. And so, our hope is that people can see that and recognize that part of this experiment, I think, of Black Rock City is about community building, relationship building, and not just amassing you know, the biggest camp possible.

I don’t think we want to force anyone’s hand at this point to say, you are too big and you need to shrink, but to encourage people to realize, hey, actually, what does feel great? And I’ve had camps that, you know, have been a couple hundred people one year and this past year were 20 and they’re like, “Oh my God, for the first time I’ve been able to sleep, and I’ve been able to go to art, and I’ve been able to talk to my neighbors rather than just try to manage a really giant camp.” And so if we can surface more of those stories, I think more people will buy in and say, “Hey, actually, yeah, why don’t I try a smaller year this year? Because I would love to sleep too.”

STUART:

So from a logistical point of view, from an operations point of view, does having more smaller camps put more of a strain on your team? Because you’re already looking at how many applications? For the 1600 camps to get placed? Run me through the numbers. What does your year look like? You and your volunteers are working on this in some fashion all year round. Walk me through what that process looks like.

LEVEL:

We start off the year right around December, January to understand tickets, who wants them, who’s interested in them, how many are they looking for, who intends to come back. So we created this Statement of Intent that people have to fill out by January to let us know.

Then from that point on, we alert people, here’s the number of tickets we think your camp should receive. We’re limited again by the number of tickets to give out, and so the more camps that wanna join the fold, the fewer there is to go around. It’s sort of like, think about pie slices, right? If you have more mouths to feed for a pizza pie, the slices of that pie get smaller, and so part of what we’re doing is assessing that.

Later on in the year, which is just a couple months later, people have to submit a Placed Camp Questionnaire that lets us know exactly their intentions. You get an initial headcount. There’s some camps out there that bring the same infrastructure and the same interactivity year after year. And then there’s ones that really like to change it up. They change their name, they change their concept, they change their theme, so we try to give the opportunity for them to explain that to us. And over time what used to be just mainly questions about your interactivity and what kind of structures you build, we’ve asked a lot more. We have sustainability goals and so we’re asking more about people’s power infrastructure, what are they doing with their waste, how are they transporting things.

We have more aspects to how the entire event operations run. We have a PETROL program for fuel. We have outside services. We also have the BRC storage program now that many camps have containers with. And so they also need to gather information so we can coordinate logistics with them so that that’s all ready and available when camps arrive.

That questionnaire, it’s a beast, I will admit, but that’s due at the end of March for most people. And then you know we do a lot of back-and-forth communicating with camps between April and June.

The map itself, I think most people are like, “Why can’t you just figure it out?” It’s truly a living thing until we get to playa because people are adjusting things; they’re adding people, they’re removing people; it’s a dynamic map. That takes the better part of the summer to complete, and we’re doing our best to give back information as much as possible, and so the last couple of years, we’ve told people “Here are your neighbors.” In July, they can start hopefully coordinating and sharing resources, or maybe co-planning events, or making sure they don’t have conflicting events, things like that. And then they go to Black Rock City.

We do assess with the Playa Restoration Team if people have cleaned up after themselves. We also try to make sure we visit as many camps as possible just to say hello and get a snapshot of what they are. My team, there’s 21 placers and about 30 volunteers altogether that include the placers. It’s not a lot of people to get around to all the camps. There are 1200 theme camps, there’s another 400 mutant vehicle art support camps and sort of volunteer camps. And there’s close to a hundred department camps. In total, we’re talking 1700 to 1800 camps in Black Rock City. The numbers are impossible to meet for us, for every one of my main volunteers to get out there, and so we actually formed a new volunteer group several years ago called PEERS and anyone can really sign up for that. You’re stopping by 10 camps and saying hello on behalf of Placement and taking some pictures of their frontage so that we know what they look like.

Many people really enjoy that experience because they are visiting camps they would zoom by otherwise. I would say 99% of volunteers come back and they’re like, “We had such an amazing time because we realized kind of some biases that we had, camps that we would not normally go into, we’re realizing are amazing Burners, amazing people, really welcoming and friendly.”

We want to make sure that the principle of Radical Inclusion is really being honored by folks, that they’re being open and welcome and engaging with people of all backgrounds.

The year end, after the event, we do ask camps to complete a post-playa report to just let us know how things go or how things went, because the decisions that placement has to make to impact people’s lives we wanna make sure that we have as much information as we can directly from the camps themselves.

Camps struggle sometimes and the neighbors talk, but you’ll learn through this self-reported process that people recognize the meltdowns that they have, recognize the struggles they have, and recognize ways they can improve. And I think that’s ultimately, we’re not here to really be judge or jury. We’re just here to understand the situation and give people more chances to come back and do better. And so that is the last part of our process, is the final sort of standings, gathering the information that we can get, and letting folks know if they can return.

That was again a lot, but it’s a long process. It takes a year. What we do see is folks keep wanting to return. And so to build upon that is requiring more people for me to manage, more camps for my team to manage. But my hope is that we can kind of continue to grow the volunteer team too. We are interested in getting more people. You know, I think the ARTery has a couple hundred ARTerians as volunteers. That could be a future for Placement, but it’s just about finding the ways we can plug people in.

STUART:

If you said the number of applications, I missed it. How many people get a “no” or “try again next year”?

LEVEL:

We accept about 90% of camps that apply. The theme camps that apply, is the main part of what we deal with. So there’s about 1300 that applied in 2023, and we accepted about 1200, and that hundred that we didn’t accept, usually it’s camps that, you know, there are some folks that are like, “Hey, I have a hundred people and we’re gonna put on two yoga classes.” And so we’re often thinking about proportionality, “How many people do you have?” not exactly “What are you doing?” We try to stay content neutral, but, you know, how much are you doing? How much can a hundred people reasonably do without burning out? A hundred people can do a lot. And so we sort of see that based on what we see across the city. So we kind of compare all 100-person camps to other 100-person camps.

We also have five person camps. What’s reasonable for five people to do? And we will place camps with only five people and say, “Hey, actually, you don’t need to be doing everything, something every day. You can be doing something, a couple of things, a couple of times a week.”

STUART:

That’s good. I know some camp organizers who will be really happy to hear that, or at least at that level of detail. I know a lot of people when they’re deep in that extremely detailed questionnaire, let’s not call it an application, they’re like, “What if I do something wrong? Is there a wrong answer somewhere in here that will immediately pop open the escape chute and drop me down into purgatory?” So that’s good.

So camps who were in good standing from last year are pretty much a shoo-in for getting placement in the year to come. And you try to make room for some additional camps until you absolutely run out of space, which is probably next year.

LEVEL:

Yeah. I don’t think I want to see a city where there is no open camping. We don’t want to make everything completely bureaucratic, so I think we’re full. So we’re going to keep trying to figure out what that impact is on the camps that do still want to keep coming back. I think, again, I mentioned this pizza pie analogy. You know, we’re not growing the size of the pie. And so if people can deal with us trimming two, four, 10 spots and tickets from them to still remain, that is one scenario we could maintain.

It would be interesting to go through an exercise to hear from the community: What do you wanna see more of? What do you wanna see less of? And that could help direct us in making some decisions. And if people wanna see more of a thing, you know, how do we incentivize that thing through the mechanisms that we have? So without a whole lot of data on that yet, other than just anecdote, we’re still trying to just keep the doors open for everyone to be there.

STUART:

People do vote with their feet. And, yeah, you mentioned the word bureaucratic, and there are some processes that might be accused of being bureaucratic processes. In a regular city, we call them zoning and code enforcement.

Now, zoning is real. It’s not like, you know, somebody drew a map and carved it into zones. But over the years, Placement has, I don’t know, has it created neighborhoods like Kidsville and Gayborhood? Or assisted and facilitated in that? Because it looks like, from this distance, there’s some very definite ideas about dividing the land into different areas for different types of use and different times of day. Tell me a little bit about your outlook on our version of zoning.

LEVEL:

Great question.The only formal zoning that we have in Black Rock City is large-scale sound. That is where, you know, 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock is where people can blast their speakers as loud as they want, as long as they face out to the open playa.

STUART:

For the new listener, 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock are at the extremities. Think of Burning Man as a clock face, as an old fashioned clock face, you know, the kind your grandpa used to have, with the Man being at the center of the clock, and the streets, the radial streets are numbered like, but not all the way up to midnight. They’re from 10 o’clock on the left side over to 2 o’clock on the right side, and that’s where the big sound camps are these days.

LEVEL:

Yeah, I think I’ve talked to Harley, Harley K DuBois, and she has acknowledged that part of the reason Placement even formed in the first place was because they had to push rave camps out on the edges because when they were sort of central to the city, people were complaining and it just was a nightmare for people who wanted to sleep, things like that.

STUART:

And then the solution was more of a nightmare because the decision was made to place rave camps a full mile away, and people driving back and forth between the main camp and the rave camp, there were some tragic accidents. That kind of led directly to the shutdown of cars, and turning it into a pedestrian city, but also made us have to deal with, you know, we can’t push that sound system a mile downwind. We’ve got to figure out other ways to deal with it. Let the people who love to groove loud, let them groove loud. Maybe the people who like to sleep, let them get a chance to sleep too.

LEVEL:

I think this point, I’ll go back to your original question in a minute, but I think this point is really fascinating, right? Burning Man started out of disorganization and just people showing up to the desert and not needing a street grid, not needing anything, and there’s a beauty to that. And as more people show up over time and more challenges occur with more people showing up, you start needing to create rules and you start needing to create systems and bureaucracies. And I think that there is this tension in the culture that is about “Why does the org come up with so many new rules?” It’s an interesting space to work in because we do get to think and create what we think makes sense with the least application of rules as possible, but also recognizing that they’re needed when necessary. And that’s kind of where zoning comes in. Zoning is, when cities were originally forming, you had industrial things and highly pollutant things right next door to where people were living and eating and drinking and bathing, and so they had to start thinking, how do we make a safer space? How do we make this work for everyone? That’s sort of the evolution of how it also occurred in Black Rock City, so…

Our team really wants to maintain some of the lawlessness that is part of the beauty of Burning Man. And so I don’t think we try to zone a lot. We recognize sound is a big thing for people. That’s the only thing we zone.

You mentioned the Gayborhood, which people also call the Queerborhood. You also mentioned Kidsville. Those are self-organized bodies. And another principle that we apply in placement and mapping the city is honoring where people want to be. Even though Placement will move camps around, we generally try to honor where people want to be and who they want to be around.

What happened with the case of the Queerbohood is that one queer camp showed up and then another one showed up. They were friends maybe already, or maybe they became friends on the playa and said, “Hey, next year, let’s ask Placement to be right next door to each other.” And there becomes a tipping point where in two camps become four, become eight, become a certain number where it starts feeling like a real neighborhood. Placement isn’t actually defining that, we’re honoring what people want to do. And then we’re also recognizing that, if we apply how we all show up in our regular neighborhoods and lives and in cities that we just navigate throughout the world, culture comes from people and people start embedding themselves in space. As the mappers of the city, we are very careful to honor that as best we can, while still, again, helping people realize that change is something that’s just part of the design process.

I’ve come across points where it’s like. Like, no one seems to like death metal anymore. I don’t know how many people did in the first place, but there’s a lot less of it on playa. I’m like, do we just need to create a neighborhood around a plaza or something that’s all death metal so people just know you can avoid it, or you can go there depending on what your preference is? Because when we’ve tried to sprinkle them around, it really causes a challenge.

STUART:

Wow, well I guess that does kind of line up with the sound zoning, which I think everyone could get behind. But there’s a risk of being creepy there, of ghettoizing, right? Of just saying, “Why don’t all you people in the black trench coats, camp over here and listen to your music as loud as you want?” I don’t know.

LEVEL:

Yeah, yeah. 100%.

STUART:

I was very glad to hear you talk about the origin of the Queerborhood because, I think that self-organizing is why, Black Rock City is, I think, one of the most queer friendly places on earth because of that, and because it’s a long history of that.

LEVEL:

There are camps that actually are queer and say, please don’t put me in the Queerborhood. I don’t want to be there. I want to be with everyone else, so, these politics…

STUART:

Not everyone wants to live in the Castro.

LEVEL:

Not everyone wants to live in Castro. Right. Exactly.

STUART:

to make a San Francisco analogy I’m sure everyone will get.

OK, we talked a little bit about zoning. Let’s talk about code enforcement. You guys do find yourself in the weird position of enforcing rules that aren’t really rules. We’ve had this conversation before. The 10 Principles are not something that can be violated because they are not phrased as commandments, as rules. However, if somebody screws up badly enough, the community doesn’t want them there anymore. So let’s start with when a camp does a bad job, whether they’re poor standing for being too messy, leaving too behind too big of a mess, for being too commodified, whatever. What are the steps you take to help ensure that doesn’t happen again?

LEVEL:

Our first step is actually just to try to understand the actual situation and try to get as objective a view as possible to say, what was going on here? There’s classic cases, people just pointing at a camp and saying, “Well, they’re a complete plug & play. There’s a bunch of sparkleponies there. Don’t bring them back. Ban them!”

I don’t think that initial accusation equals the actual final verdict. And so we try to make sure that we are making judgments based on actual information. Oftentimes people see an RV wall and they think that’s a plug & play. And many times that’s actually just a corral of maybe a bunch of staff that are busy being staff and don’t want to put up a bar to engage with people because they’re running something else in the city. Same with, it could be a corral of artists that are just working on their art and don’t necessarily need people coming into their camp because they got to sleep because they have a burn the next morning, you know. So I think that those are things to consider.

Assuming we found a camp that maybe is not doing everything right, we really try to believe in people having good intent and wanting to do the right thing, and that their failure isn’t just something that the entire camp needs to experience but to sort of reflect on.

We believe in multiple chances, you know. I think with feedback and with specific feedback that gives people a chance to say, “Hey, oh, I didn’t realize I was being viewed that way. I didn’t realize that wasn’t good enough.” There’s probably somewhere in the middle that we need to meet. We really try to believe in people’s willingness to learn and grow.

This is the part of our job that we love the least. Even myself, I joined the team not to be a code enforcer. I wanted to do SimCity and just watch what happened. We are on the front lines of people saying, you know, especially around turnkey camping and convenience camping to try to stamp that out. Also there’s sometimes camps we get reports about camps that are really unneighborly and will say mean things to their neighbors and pull pranks that aren’t really funny, but just more annoying than anything. So I think that depending on the thing, we try to show up and say, “What’s really going on here?” Also show up and say, “Hey, can we resolve this in a way that doesn’t feel punitive?” Maybe there just was a misunderstanding. And maybe there could be a better placement in the future. It just happens to be oil and water that didn’t belong together.

And then when it comes to issues around decommodification, I think that there is a little bit of a harder line there because I think we definitely don’t wanna see pre-packaged Burning Man experiences for $5000, that someone could just sign up for and show up for, and not pull the weight and pull the culture the way we want everyone to. We don’t want this just to be an Instagrammable bucket list thing. It’s a community, it’s an experiment, it’s an experiment in community; we want people to show up a certain way and so I try to just have reasonable conversations with people. Sometimes they haven’t had good guides to help them learn what Burning Man is, and learn how to distribute leadership and responsibility, how to empower people to be their most creative selves, you know So I think that that’s not just placement’s work. I think that’s kind of the work that we’re all trying to do as we’re in our own ways, as we interface with people that show up at Burning Man.

STUART:

So that tour operator who’s leveraging the Burning Man brand to make a buck off of our back, how do we find out about him?

LEVEL:

Really I think the eyes and ears are out in the community. I’m not looking for those packages myself. It’s funny. One way that we find out is the AmEx concierge that says, “Hi, my client is looking for an RV and a bike and all these other things and a ticket to Burning Man. What do we do?” And it’s truly just like a concierge company trying to help their client. And then we do rely on just people letting us know, you know. There are unfortunately packaged experiences and branded experiences that are like, “Look at Burning Man!” And this isn’t just in English. We’ve seen this in other languages.

STUART:

Oh yeah.

LEVEL:

People want to commodify Burning Man. It is an amazing thing. And so I think there are people out there that feel like you can make a lot of money off of it. And so we just need people to help us put their feelers out and let us know once they do see that.

Once we find that we do try to understand who are these people behind this and is this a malintent or is this really just someone that didn’t really know, they are trying to do things within the spirit of the Burn. So it comes from all angles and all places. And where we just sort of catch what we get. And sometimes things get past us and show up in Black Rock City and we hear about it once we get there, or we see it ourselves once we get there. And so we try to address it on the spot as well.

STUART:

So of the 1200 theme camps that were placed this year, how many of them will not be invited back as a placed camp next year or has to take a year off?

LEVEL:

Before I share those numbers, we do have sort of a scale in which we’ll slap people on the wrist all the way to not inviting people back. We generally are factoring in, do we see a pattern of behavior here? Have we given them years of explanation and chances to improve or not?

STUART:

Yeah, it wasn’t a newcomer’s mistake. It was more of a bad actor or a habitual behavior. Okay.

LEVEL:

Yeah. What we’re trying to suss out is, is this group of people or this individual willing to learn? And it’s easy to, you know, I think because we’re a trusting body, we’ll take people at their word. So if they say, “Hey, oh yeah, we’re sorry we messed up. We’ll do better next time,” We’re going to trust them to do that. And then if we see the same behavior come back the following year, we’re like, “Wait a minute, we thought we had this conversation. Why are we seeing the same mistakes?”

So anyway, in 2023 there are five camps that we have asked to take some time off, anywhere from one to three years. And that’s five out of 1242 theme camps total.

STUART:

Wow.

LEVEL:

In addition to that, there’s like 35 that we’ve given warnings and another 30 that we’ve sort of said, “We’re going to limit your size, or limit your tickets for the following year.” But really the only ones that are forced to take time off are five. And that’s, you know, a tiny fraction of the community. I think that it’s easy to focus on these outliers. But there’s by and large, most camps are doing great.

STUART:

Yeah, and those people are welcome to go try to set up their camps in open camping or what’s left of it. I just want people to understand, they’re not barring people from the event for these types of behaviors.

LEVEL:

Correct. Yeah. They can still show up. They can still buy tickets. They can still set up a camp. We’re just not going to give them access to all of that through placement.

STUART:

Okay, I got a couple of questions, crystal ball questions. I want to look forward, we spent a lot of time looking back. Looking into the future. And once again, you know, a reminder that the annual cycle that we have is an urban planner’s dream, right? that iterative development of the city. What about gentrification? We’ve been going through that in multiple iterations. What else can we do to cut down on the number of people who are living in gated communities in Burning Man?

LEVEL:

You know, I mean, I don’t think that many people are living in gated communities. It’s interesting. I try to think about my own evolution as a Burner and what I, what kind of like accommodations I had when I first started. I came in a monkey hut and just a Coleman tent and it was pretty basic. And I’ve heard of even more basic situations, people with no shade structures at all.

And people go and they learn, right? It’s not a “keeping up with the Joneses” kind of thing, but I think people realize there’s easier ways to show up, things that are less harsh, things that are easier to clean up after, and things that are more sustainable. And I think that feels like gentrification, and maybe one could argue that it is, but I think over time there’s other people that graduate to trailers, or RVs, because they’ve decided that this is important enough for them to invest in these toys that’ll make their experience better. You can’t blame anyone for that.

Technologies change. The climate’s gonna change too, so we’re gonna have to adapt to all of that. So I think about it less as gentrification, but how are we adapting to the environment that we’re in and how are we trying to make it both easier for ourselves and more environmentally friendly.

When I look at a crystal ball, it’s not about how do we make sure that everyone still is living in a shanty town sort of environment, but how are we actually helping to, do we really need everyone to bring all the things that they bring? People lean super hard into Radical Self-reliance and that as wonderful as that is, there’s also Toxic Self-reliance where you’re not realizing that…

STUART:

Oh stop. What you call Toxic Self-reliance, I call bringing enough surplus goods that you can be a gifting maniac. You can be a High Plains Gifter with all that stuff. Radical Self-reliance totally feeds into gifting in my book, if you’re of that mindset.

LEVEL:

Absolutely. Maybe I’m thinking the margin beyond that, which is: I need to bring two of everything, not to give away, but just as backup.

STUART:

My motor coach has to have a fireplace for those cold nights!

LEVEL:

Or that. So, when you start multiplying that by the number of people that go to Black Rock City, I’d love to see the conversation turn into “What can we share? What can we share? What do we not need duplication around? How do we use a resource and share that resource so that we’re not bringing hundreds of plastic water bottles out there, but communalizing that, you know, there are net gains.

I think there’s an argument to say that. Maybe that requires more money and people of a certain income level can afford to do those things, but I would hope that BRC, Black Rock City, is where we can actually think more creatively about that and try to figure out ways that it’s not just driven by “only the wealthy can have the nice things,” right? – and the environmentally friendly things.

STUART:

No, sustainability was my next challenge for the future. It’s the old ‘too many generators.’ I understand that your team is making some inroads into helping people organize and to share resources. Tell me a little bit about that.

LEVEL:

Yeah, we have this thing that we started a couple years ago called Humans United for Better Sustainability. Essentially what we’re trying to prioritize in mapping is groups of people, groups of camps that say, “Hey, rather than five camps bringing five small generators that have to be fueled, we’re going to go in on a cleaner, more efficient generator that’s larger, that we can all share and build a power grid across them.”

It’s not just about generators, you know. If people are communalizing around carpooling even, we wanna hear that, and we wanna honor that, and we also want to physically map that together. And so, HUBS is what the acronym is, we’re encouraging people to hub, to say, “Hey, actually, if you have things that can be shared, create a hub.” And if you don’t know who to share that with, there are lots of different spaces that we wanna help support people going to, both online and in person, where you can network and say, “Hey, actually I have extra storage space in my container in Reno, who wants to share that? We can go in and split the cost together. And then we can actually place it together on Playa with the help of Placement to say, these two camps need to be next door to each other.”

So we’re trying to figure out more clearly who is sharing what, what are they sharing, putting them in the map first enables the resources to sort of flow a little bit more easily.

There’s also camps that are part of the fuel program. We’re logistically actually trying to make sure that they’re clustered in a way that gets more efficient for the fuel routes of the PETROL program, as well as BRC storage. You know, everything… To build a city out of scratch takes a lot of power and a lot of fuel. And we’re doing our best through HUBS to minimize the amount of sort of space that they take and ways they need to circulate throughout the city. We’re talking about routes that are miles long. If we can cut down those routes for fuel trucks, like we’re gonna have some net impact on that. So all of that requires spatial planning as well as logistics planning. And that’s what I’m here to do as well.

STUART:

Last question about the future.

I’m getting the sense that we have kind of a blighted downtown with the Center Camp Cafe since we took out the coffee bar. What do you see there? I know there’s a lot of people thinking, coming up with great ideas for that. What would you, what would your solution be?

LEVEL:

We’re actually gonna be proposing a redesign of the area. Rod’s Ring Road has been a confusing street for a lot of people.

STUART:

Oh my god. You think it would be impossible to get lost in that town, but yes, that’s the culprit all the time.

LEVEL:

Yeah, people get turned around. So I think what we’re planning to do is to reconnect Centre Camp’s physical space with the street grid of the rest of the city to have A Street, B Street, C Street all cut through. So there’s still have Center Camp and the shade structure of that Centre Camp in the middle and a big plaza there. We have an opportunity there by weaving the street grid back into Center Camp to invite people back to go there and check it out.

STUART:

And if we have another rain year, it will be a waterfront.

LEVEL:

Right. Yeah.

STUART:

It was pretty wet around Center Camp this year.

LEVEL:

Yeah. What actually happens around the plaza, we’re really looking at, there’s been a lot of department camps where staff is, and I think that an older idea of Center Camp was thinking about it as a civic center and where all the civic services are. We’re saying maybe it doesn’t need to be that because sometimes civic centers shut down, especially at night, and we want to invite people there at night as well. So we’re looking at things like that.

What happens under the big top, I’ll be at the table to help think about. But I wanna think about what’s around there too, you know. I think that there’s an opportunity, we’ve had varying ideas. Some folks have said, “Hey, what if we had all the green theme camps that just surround it? So everyone knew that was the concept. Or what if we had all Regionals, the Regional bodies and camps from different parts of the world, like, it’d sort of be a little Olympic village around Center Count Plaza?

STUART:

That’s an exciting idea.

LEVEL:

Yeah. There’s different ideas about what we can put there.

The best thing about Black Rock City is we can iterate and try things. And so maybe we’ll try one idea this year and another idea the following until something really sticks.

STUART:

So why did you go to Burning Man in the first place back in 2009, Bryant?

LEVEL:

I grew up in San Francisco. I was born and raised in San Francisco, had sort of heard rumblings of it, but didn’t ever know anyone that actually went. And one year, a couple friends of mine said that they were going, and I was like, “Hey, I didn’t know you had any interest. I’ve had this interest, we just haven’t talked about it. Can I just like jump on board with you all?” And so I did.

I think the thing that probably caught me the most was seeing the art and saying, “Wow, the art is so beautiful and interesting. I really want to be there to interact with it.” I came for the art, but I keep going back for the people. It has become so much more than just art. I actually don’t even in my job right now see that much art. I’m in the city, I’m with the people. The culture and the vibe is so palpable. That felt like it hit every string in my body and resonated. And so that’s why I go back.

STUART:

Thanks for listening, invisible Friends. Burning Man LIVE is a fully decommodified media artifact hurtling through the invisible interwaves in your direction straight out of the Philosophical Center of Burning Man Project. I’m Stuart Mangrum and I want to express my appreciation to everyone who helped make this episode possible. Level Placerman. Vav Michael Vav, Tyler Burger, the whole production staff, the whole Placement team, to everyone who brings a camp to Black Rock City. Thanks to you all. Thanks to you dear listener, for, well, for listening, for liking, for reviewing, for donating at donate.burningman.org, and for sending us mail at live@burningman.org.

See you next time.

Thanks, Larry.

more

Bryant Tan

Bryant Tan Stuart Mangrum

Stuart Mangrum