A People’s History of Burning Man – Volume 2

Back by popular demand, more stories from Burning Man’s oral history project, an ambitious endeavor to track down and talk with people who helped shape the culture as we now know it.

Stuart and Andie remember to remember the most memorable parts. Here’s a fresh batch:

- Chris Radcliffe, artist, con artist, prankster, and shadow founder of Burning Man (perhaps), shares stories of how the Cacophony Society would prank the media and how the Black Rock Desert drove up his fears, then dispelled them. He also hints at the larger-than-life impact of the Billboard Liberation Front.

- Candace Locklear, aka Evil Pippi, a perturber and social experimenteer (new word) shares how she helped Burning Man manage the mainstream media in the late ‘90s. She also talks about cutesy culture jamming as a scary clown.

- Summer Burkes, a Southern belle punk, was the media liaison for the DPW. She sees the early days of Black Rock City as the love child of comically aggressive punk rockers and air-kissy techno industrialists. She embraces their uneasy peace.

- Steve Heck brought 88 pianos to Burning Man in 1996, stacked them in a tall circular “piano bell.” People beat it into a cacophonous soundscape until he burned it. That was after he almost died wandering the desert. Then he cleaned it up, and did it the next year, and the next year, and taught the BRC teams the art of packing and moving big stuff.

- Dr. Hal Robins is a beloved Renaissance Man of stage and story, a Cacophonist, an Uber Pope of the Church of the Subgenius, and a mellifluous philosopher of sesquipedalians. He shares about the inventiveness and serendipity of Burning Man and why it matters in the world.

Part 1 of this series: burningman.org/podcast/a-peoples-history-of-burning-man

journal.burningman.org/category/philosophical-center

burningman.org/programs/philosophical-center

The What Where When Guide is here.

The 1996 Helco commercial is here.

Transcript

STUART: Hey everybody. Welcome back, invisible friends, to another Burning Man LIVE.

We did a show a little bit ago that we call People’s History of Burning Man, showcasing some of the oral history work that Andie Grace, Actiongrl has been doing, and a lot of people wanted more. So we’re here to give you what you want. Give the people what they want, which is more stories of old-timey Burning Man and some of the people who helped get us to this crazy place where we are right now. So, another installment: A People’s History of Burning Man.

ANDIE: That’s right, Stuart. More has always been my favorite number, and more is what we’ve got.

I’m so glad to get to bring everybody along on the good time that I’ve been having talking to these people. And we are still kind of in the way-back phase of the project. And so this week we’re going to hear from another five early contributors to that thing in the desert.

STUART: And by the way, that was actually Burning Man’s original name. Did you know that?

ANDIE: I don’t know if I knew that, Stuart. That’s a great example of how people remember things a little differently from time to time, and that is one of the hazards of this process. We’re asking people for their stories as they remember them, which after 30 plus years and a lot of dust, they can get a little lossy; indistinct, if you will.

STUART: I still hold the copyright on that thing in the desert, and TTITD. And technically speaking, I just need to pay myself, I think, 50 cents for each time that I say it.

ANDIE: Or someone gets a tattoo.

STUART: I think that’s free. Just to keep it moving, right, keep the meme in the world.

So, people’s memories are funny things, especially those of us remembering things that happened, I don’t know, 30 or 40 years ago. How do you deal with that? If somebody says something that you suspect may not be completely accurate, may be a relative truth for somebody, how do you deal with that?

On one hand there are a lot of jokers and pranksters in our midst who may just be making stuff up because they can make stuff up. And, also some of us are getting on in years. Do you jump in and correct people? What’s the best way to deal with that challenge?

ANDIE: We keep rolling and maybe I write something in the field notes to flag anything that is sketchy and needs correction or shouldn’t be put out in the world as a truth.

It helps that I’ve been here for 25 years and studied this deeply with most of my life’s work. But I tried not to, like, correct a subject unless it’s to say, maybe get more detail out of something, or elicit a response more about their opinions, get their memories of what happened next.

I have to respect the integrity of the memory process and let people tell their stories as they remember them. And like you said, different people hold different truths.

STUART: Yeah, so somebody says, for instance, that Burning Man was actually founded by a sentient kombucha that networked into a bunch of hippies’ kombucha jars, you’re just going to go with it and maybe stick a note in the field notes.

ANDIE: Well, I might ask where they found that out and how they came to believe in it. Everything is possible, and especially when it comes to who started what and when. Some people did take notes and that is critical. Some of them do sit there with them open, but hopefully they’ve just refreshed their memory as best they can, and we put it all on the shelves and leave it to be sorted out as a mass of stories that together make up truth.

STUART: The truth is in there somewhere. Oh, the truth is out there somewhere. So maybe we should have one of those disclaimers ahead of this episode:

Opinions expressed here are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views of Burning Man Project.

Let’s get into this. Let’s hear some stories.

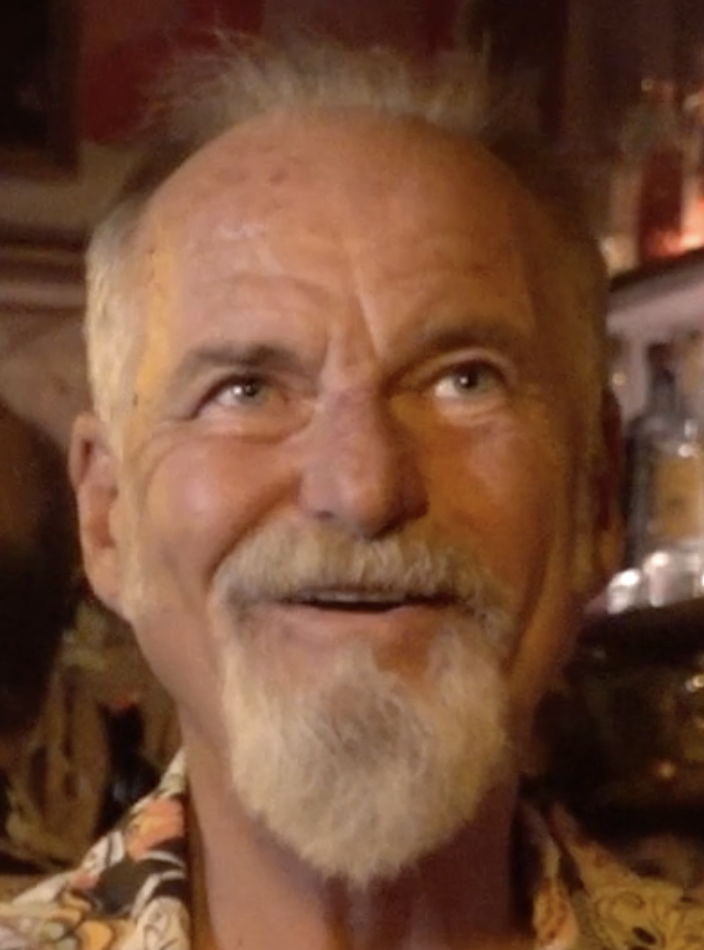

Chris Radcliffe aka Christina aka Huge Chrysler Jones aka Timothy Liddy; the guy’s got more aliases than Gordon Liddy. How do we describe Chris Radcliffe? Prankster, Cacophonist, bullshit artist extraordinaire, one of the shadow founders of Burning Man? He was the third partner in Central Sign, which is the company that Michael Mikel and John Law were operating when they first brought Burning Man out to the Black Rock Desert.

ANDIE: That’s right. And I met Chris for the first time on a trip to record him at this cool studio near his home in Portland, Oregon. The studio was set up all like this dark bar, and we went in out of the sunlight, which was a sunny day in Portland, and boy, did I go on a ride with Chris Radcliffe.

I will have to say that, there’s a content warning in his story. He does describe simulated suicide.

With a pedigree like Chris’s you have to expect that it was a lot of fun. He had some pretty intense, poignant and beautiful stories about his Burning Man days. He clearly loves the Thing.

CHRIS RADCLIFFE: I got introduced to Cacophony and my life blossomed. What became the largest extended family that I could ever imagine laid itself open to me and it changed my life. It really did. We were doing all sorts of things that were outside the mainstream, things that I never imagined were really possible, and it was very enlightening.

I was running around with a group of people that didn’t really seem to have any limits and certainly weren’t married to the status quo. I’ve got a list over there of all the events that I was doing, but Burning Man proved in the long run to be the biggest outgrowth of that.

About my first time going to Burning Man: I had never been out to the desert before, and I signed up for this thing that we were calling a Zone Trip. And I thought, all right, fine, I’ll sign up for that.

I ended up driving to San Francisco, picking up these two girls that were working for a magazine there at the time, and getting a couple of kegs of beer—I remember it was Emperor Norton Beer—and heading out to the desert for the first time.

I was driving around a 1969 van with about a quarter of a wheel of play in the steering, and I had gotten used to driving that thing. I get out there and drive out 447, and it’s probably the first time that I’d been a hundred miles down a two lane road. And that’s a really unusual experience for most people. But then blowing past Gerlach in the morning and then following these directions got me out to the first exit onto the playa. This story is probably really common to everybody that’s ever gone out there. But at the time, it really shook me.

I turned out into that vast expanse of nothing, and our directions were “Drive five miles east and then 12 miles north.” It was still dark out. The odometer in my van was broken, so I was sitting there with a watch in one hand and a compass in the other, staring at my speedometer, hoping that I was going to get us out there. And after that initial experience of driving away from the road, and the first time you’re on the vastness of that, I started to get scared. I thought, “Oh my god, I’ve got these two girls, my wife, my dog. I haven’t checked my tire pressure or my oil, and fuck, am I going to kill everybody out here?” I started to get really panicked. “God, what have I done?”

I made the turn to head up the 12 mile thing into the middle of nothing. The sky had gotten a little lighter, and I saw this blinky light that I drove towards. It was on top of a truck. And it pulled up and I felt like, “Thank God.”

Crimson Rose was wearing some giant parachute and she was up on top of the Man statue, which I’d seen before, and it’s blowing in the wind, and I’m thinking like, “Wow. Where am I?” Michael Mikel fed me a hit of acid and shortly thereafter that I was riding around on the hood of the 504 car, which was this old Oldsmobile that had gotten crushed in the earthquake in San Francisco. Me and a guy named Sebastian Hyde were riding on the hood of the car at 40 miles an hour, holding on to the ear of a rabbit’s head. You know, and the guy is saying, “Where do you go?” I said, “Just go where the rabbit points!”

Leaving Los Angeles in the kind of wrecked state that I was, staying in Big Sur and trying to bring a little peace back into my life, I became fearful that I’d gotten so far out on the edge of things that one small disaster, breaking my right leg, I wouldn’t be able to drive, something else happened, I’d be unemployable. I was so on the edge that I was in fear of any kind of risk at all up until that point. When I got off that car after surfing it around the desert, that fear was gone. And it never came back. And that was my introduction into Burning Man.

ANDIE: What were you and your friends up to in San Francisco? There must have been a lot of wild things going on.

CHRIS RADCLIFFE: Ha ha ha. So, one of our friends, Peter Doty, decided that he was sick of listening to a bunch of whiny protesters going after anything around. And Peter was totally unassuming, right? He came up with the idea that as a group we should protest the lamest thing that we could think of, and that turned out to be the exhibition of the film Fantasia that had been released for the first time in 20 years.

And so for three consecutive weekends, we went out to this theater on Geary Street and set up our little coalition of protesters that included a group called SPASM — Sensitive Parents Against Scary Movies. We got the Fatso Crew to come out and protest Dancing Hippos and its representation of people. I personally was a Christian preacher, preaching against the sane-ism and stuff in the wizards thing. We had a couple of other groups, right?

So we’d show up, and we’d do this on a Sunday afternoon because it was a slow news day. But we would also put out a press release. We’d put out press releases on a really boring day in San Francisco. We eventually started attracting media. And, by the third weekend we had a film crew out there that was going after us. And the fourth weekend, same kind of thing, but we got bored and we quit. We went on to the next thing.

Time magazine decided to pick up on that and published an issue called, “Are We a Nation Full of Whiners?” And when you opened it up, it was all of us. So we had completely pranked Time Warner Media and stolen the cover story off an entire issue of what was then a pretty well-respected publication.

Several months later, on April 1st, also called St. Stupid’s Day because we have a long-running parade in San Francisco that basically shows the absurdity of all the things we’ve done, we press released the Wall Street Journal and told them that we had completely pranked Time Warner and they ran a story on that on St. Stupid’s Day, so, really valid stuff.

I didn’t realize that you could manipulate media to that level before. I knew you could pull it this way or that way, but not outright steal the whole idea of it. And we kind of ran with that.

It culminated in this event on the Golden Gate Bridge, during the Bay to Breakers run, which in San Francisco is this large thing where people run across the Golden Gate Bridge up to Sausalito, and that’s the end point, all that. The Chronicle at the time, the local newspaper of record, would still publish how many people had jumped off the bridge.

ANDIE: Suicide.

CHRIS RADCLIFFE: Yeah. And it got up to 996 and that caught our attention and so we kind of timed this whole thing and it worked out serendipitously with the Bay to Breakers run. We had a hundred people set up on the north end of the bridge wearing jogging tags and little signs that said #1000. We ran into the middle of the bridge meeting the crowd coming out, staged a fight and threw an effigy over the side.

And I happened to be standing on the road when the first media truck pulled up and they’re like, “What happened?” And I said, “Timothy Liddy killed himself.” And they’re like, “Who’s Timothy Liddy?” And I said, “Give me your card. We’ll send you a press release.” I wrote up a thing that said Timothy Liddy, a long-time San Francisco scenester, killed himself today on the Golden Gate Bridge,” and 1,000. The thing is is, Timothy Liddy was my Cacophony nom de plume, and so I claimed to be the number 1,000th suicide off the Golden Gate Bridge, and the Chronicle published it. These were the kind of things that we were doing.

There were also a lot of billboard hits that we did. We had a thing called the Billboard Liberation Front. Basically I was in the sign business. Another guy that I’m not going to name was in the sign business and we would take the equipment that we have to make these very professional edits in these large billboards that were completely jarring to people that would see it because it looked like the corporate message, but skewed our way, and we had a lot of fun with that.

ANDIE: Ah, the Billboard Liberation Front. But let’s save that story for a future episode so we can really dive in. What do you say, Stuart Mangrum?

STUART: All that.

This time around: Candace Locklear, aka Evil Pippi, part of Burning Man’s first media team, a PR professional who brought her PR chops out to the desert in the very earliest days, I think before, or the very dawn of Media Mecca; also a notorious porn clown, who, with her late husband Ouchy the Clown, made a lot of people laugh in an extremely awkward and uncomfortable way.

ANDIE: We love our clowns. Candace was one of the first friends I ever made at Burning Man and really, I learned at her feet, and when we were campmates at Motel 666 and I was just trotting around loving Burning Man, I saw her face coming back from a volunteer shift and I realized: somebody’s behind this whole thing.

Hearing her stories made me want to volunteer that year and help out. So, she’s old school (if I’m old school) and a hardcore brassy, no bullshit, Southern belle who…she’s so fiercely dedicated to this culture in her life all day long, and helping to preserve its outrageous spirit. That’s how she ended up helping us oversee, or even create Media Mecca, with the presence of the media at present Black Rock City; she saw it and said, “Marian, you need my help.”

And our very own beloved kbot, Kirsten Weisenberger, sat down with Candace Locklear in 2022 for her oral history interview.

CANDACE: Evil Pippi is a character I came up with when I helped start Media Mecca, with Marian, in 1997. I started off as White Trash Barbie, but that got boring and hard because the wig was too hot on my head. So I switched it to evil Pippi Longstocking, because I was really kind of a bitch to the press. I do PR in my everyday job, and usually you’re very solicitous and, you know, really wanting the press’s attention. But at Burning Man, we really didn’t want that much press attention. So I got to flip my character and sort of be a bulldog on the playa, and an evil Pippi Longstocking helped me embody that attitude.

KBOT: You got to be that person you couldn’t be in your 9 to 5.

CANDACE: Exactly. Yeah, which is what a lot of people I think are doing, and they’re living out their avatar dream on the playa. And it’s stuck. I have the tattoo. Actually, my Pippi Longstocking on my arm has a Burning Man tattoo on her arm.

KBOT: Okay, so if I came to you all starry-eyed or maybe confused and said, “I don’t know how to do this Burning Man thing. Please give me your advice,” what would you say?

CANDACE: There is a lot of practical advice, but you could get that on the internet. So, I would give more advice on how to hack your good time out there.

What I usually tell people is to get lost, literally. The Who What Where When Guide that you’re given when you come through the Gate is an amazing thing to stare at when you’re drinking coffee in the morning, and to figure out what is going on that you might be interested in. There’s something for everyone.

So I recommend, you know, day two or three when you’re pretty acclimated, to look at that book, and go find some things, two things or three things that really jump out at you, and just wind your way through the playa, not on a bike necessarily, just walk, by yourself ideally, and go to that yoga workshop, or go have high tea, or go to the champagne bubble party, whatever it is, and connect with people.

And you will just change your whole experience by doing that and probably make some new friends.

KBOT: And you think going by yourself is better because…?

CANDACE: because you’re going to be more open to interactions. You soak up a lot more by doing that. I mean, it certainly takes a lot of confidence to do that. It’s not for everybody. You can certainly take a friend or go with a posse of people who just want to walk around for the afternoon. But I think to really get the most out of it, if you go by yourself, you’ll discover a lot about yourself and you’ll be able to meet new people more easily.

KBOT: I am going to ask you for one more piece of advice.

CANDACE: Okay. Let’s see. I’m trying to think of a good piece of advice.

If you like pranks, and I certainly do, I think a very fun thing to do is to photobomb. So there are a ton of people out there, especially hot chicks, who are getting their photograph taken and often by pro photographers. And you can tell by the gear that they have, and usually by the sparkly outfits that they’re wearing.

There’s a lot of that going on. And some of it is probably for commercial use, or for other kinds of ad campaigns. All kinds of things are going on that are not supposed to go on. So I feel like it’s fully in everyone’s right to photobomb. But there’s a right way to do it, and there’s a wrong way to do it. You know, you really aren’t trying to be too aggro or, you know, trying to get in a fight. That’s the last thing you want, but you can have fun with it. And I think that’s a great way to acclimate these people who are trying to capture imagery on the playa, that they’re at an event at Burning Man, they’re not in the public. So, they have to kind of deal with the confrontations, and it’s training them to deal with these confrontations.

So I’ve done this with some people. I dress up as a clown at Burning Man so it makes it extra easy to be… act the fool; approaching the photog… we don’t even really approach the photographer, just slowly easing in to the shot, and smiling, you know.

And if you smile, then they have to deal with you. And just being behind the hot model and doing a funny pose, then they get an amazing shot, then they usually are down with it.

And then afterwards we usually engage with the photographer or with the model and have a hug, and it’s really fun, and it’s a great way to break down what could be a contentious situation because there’s a lot of people who hate the fact that people are using Burning Man as a backdrop, but there’s also an opportunity to have fun with it and maybe educate them on the right way to do it.

And also to get a cool shot. Maybe even get a pro shot out of it if you exchange contact info after the event. So, um, photobomb.

KBOT: Amazing. Black Rock City is not their photo studio, so you have every right to be in there doing whatever you want, really. That’s awesome.

CANDACE: Yeah. It really has to do with your attitude, and being positive and curious about what’s going on versus, you know, bitchy and having sort of a holier-than-thou attitude, which, you know, it’s a fine line.

KBOT: Yeah. Like who’s going to get angry with a friendly clown?

CANDACE: Most people don’t. Although I’ve been known to scare a lot of people because I have a pretty frightening clown. I tend to put on clown makeup and not take it off for three days. I call it the Three Day Face. And so, it’s pretty scary. It’s streaky, it’s faded, it’s smeary. And, people have a hard time, some people have a really hard time with clowns, and those are the people I want to hug. So I kind of make it a, myself, I like to go out and hug, hug the people who are running from me. Again, it breaks down some barriers, and it doesn’t always work, but chasing people around can be hilarious. It’s my own brand of fun.

Again, it’s just being provocative out there. You get to take more chances to engage, especially if you’re in a costume. I feel like the playa is just like The Cartoon Network. Everybody’s in these crazy little outfits, and some are there to be sexy, and some are there to be silly, and sort of engaging with all kinds, makes it even more exciting.

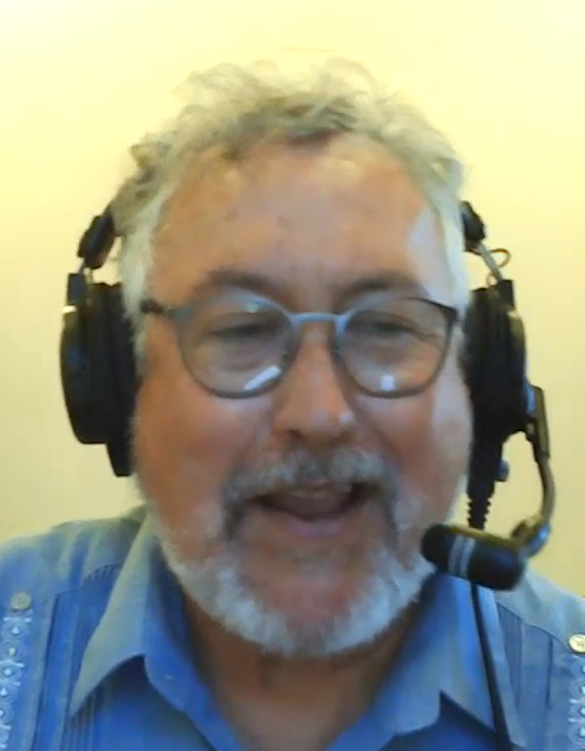

STUART: Summer Burkes came to us as a journalist first, and somehow managed her way straight into the Department of Public Works, which is an odd trajectory, but, tell us more about your friend Summer.

ANDIE: Another dear old friend. Hi, Summer. Sorry, this is not nepotism. We met at a Media Team meeting. It’s just that I’ve been around a very long time. These are our contemporaries, right?

Summer and I met on the Media Team as young volunteers. We made fast friends, and she became the Media Mecca liaison to the DPW at a time when we were trying to help the press get stories that mattered, not just “come look at the crazy people in the desert.” And so having connections to these other teams of volunteers and hard workers giving up their vacation time to come out and sweat with us – we wanted to be able to tell that story. But there wasn’t always an embrace of the cameras that came at you. Even today, we’re still, we have a dynamic out there about what it means to have the media present.

So her job was to help liaison to that. And she became a voice on the blog, the Burning Man Journal. She was one of the earliest voices on the blog. She did a column in the SF Bay Guardian called Dilettante, way back in the day as a print rag weekly that was in the newspaper stands all over town. This was where you went to find out what was happening and what had happened, and it was before such underground culture blogs really existed. She’s somebody who’s, it was her job to have the notes, so Summer’s an example of someone whose memory of how this all happened, is supported by notes.

ANDIE: And how did you find your way to the Bay Area?

SUMMER: I went on vacation and stepped off the plane and my body just said, “This is home.”

ANDIE: What did you find yourself up to?

SUMMER: Waiting tables. But also on the lam from the music scene of Chapel Hill. And so I parlayed all of my experience there into an internship at the Bay Guardian, San Francisco Bay Guardian, the world’s only free, independent, family-owned weekly, at the time. Rest in peace, alternative media; and, went from intern to assistant editor, to local music editor, to Dilettante, which was the nightlife column.

ANDIE: And what about Burning Man? When do you remember hearing about that for the first time?

SUMMER: I was just waiting tables downtown. The coolest couple at the restaurant, who lived on a sailboat in Sausalito, told me that Burning Man was the most amazing thing that I would ever go to.

I first went to Burning Man in 1998. Somebody from The Org gave me a couple of free tickets, so I took my housemate Linda Chavez Lagunas, of the Cyclecyde Bike Rodeo, and we ended up emceeing for Kal Spelletich of the Semen and doing all of this other stuff, wearing piñata parts on our heads. It was amazing.

I stayed afterwards and wrote about the DPW, because I just knew that was my people. We rode around on The Bucket, which was the first DPW car, with a horse trough being pulled behind it sometimes. That was the DPW hot tub. So then Linda and I were Exodus that year, and it was just us and The Bucket, and a megaphone. And we collected a whole bunch of carloads of food and drinks and brought them to the Depot over and over.

And then, in ‘98, I wrote about the DPW in a column called We Built This City, and that was it.

ANDIE: How’d that go over, writing about that aspect of Burning Man?

SUMMER: The column got mixed reviews, because the DPW notoriously hates any type of media. I wouldn’t say hates, but definitely avoids, kind of like an aboriginal; they don’t want their souls stolen by cameras, and I kind of count myself in that number and always have. But I got yelled at for supposedly misquoting someone, but not by the person that I supposedly misquoted. And I totally went into the tent and cried. That was my first Burning Man meltdown.

Then, I became the DPW media team liaison, and wrote on behalf of the DPW to the rest of the Burning Man crowd, from out there. I was the second DPW blogger after Randall who did “Feeding Tofu to Cowboys” in ‘97. And then my, I think it’s three pieces, it’s called Days of Our Dusty Lives.

ANDIE: You said you found your people. Was there a moment that you sensed this was going to be a big part of your life?

SUMMER: Meeting the DPW, I finally found a large cohort of people who were, as it turns out now, 20 years later, also high functioning autistic! Ha ha ha! We all have a fetish for logistics and, uh, don’t necessarily need to talk all nicey-nice to each other. There’s a hilarious comical aggression that’s always present, rarely mean spirited, but it was real punk. I just felt like they were my people, and that Burning Man was not an air kissy, airy fairy type of techno fest for a lot of people, even though it was for others, it was still in the early days when it wasn’t. I mean, Burning Man was founded by punk rockers and techno industrialists, so we all had an uneasy peace.

ANDIE: So there you were, you were working DPW, but also participating in Media Mecca at a time when cameras were changing, and technology was changing, and it all kind of grew up alongside us.

SUMMER: At Media Mecca, I basically watched Actiongrl and Nurse and Marian and RonJon and Pippi and Yoms and Steven Raspa and a bunch of other people figure out how to deal with and mostly deny mainstream media. Ha ha.

ANDIE: How did you see your fellow media behaving out there during those years?

SUMMER: My fellow media out there tended to embarrass me half the time. There were some people who did not read up on it before they got there and needed a lot of taking care of, and just as an alternative weekly journalist, even though I was only an arts journalist, it was still just, they shamed our people, you know?

I remember this one woman in particular asking us, “Are some of these buildings here all the time?” I just couldn’t hold my tongue. I had to say, “You need to go read the website tonight before you come out here!” But probably nicer than that, I hope, because I wasn’t talking to anybody else in the DPW.

ANDIE: So, when you were with DPW, you did writing, but you were also out here for the whole time. Did you just write or did you swing some hammers?

SUMMER: There was no way that I could go out there and just write and not swing hammers. That was made very clear to me. The first day I had no idea and I was staying in Marian’s trailer and I missed Morning Meeting and I missed breakfast and I got a big tongue lashing. But I could take it. So I was like, “All right, all right.” So I really showed out, and I straightened up all the rows and made a bunch of A, B, C, D wooden signs, and was T-staking them in all day while everybody else had already gone off to the playa. So I had to prove myself, and not be a journalist out there because there was already another photographer out there who they just harassed mercilessly and I didn’t want to be in the same boat.

I could already feel myself just migrating from normal society and towards DPW Cacophony lifestyle anyway.

ANDIE: So what about it appealed to you?

SUMMER: I feel like I gave a lot of my energy and time to the DPW specifically, and Cacophony in general, because it is the way that the world is gonna have to change in order for us to all get along. You know, with all these religious people gunning for an apocalypse we gotta be prepared. I joke that Burning Man is apocalypse practice. It’s Happy Max. It’s summer labor camp. And you learn so many different things out there with your body and your mind, and from other people. There’s just no other incubator like it on earth.

STUART: Steve Heck, known to many from those old days as ‘that guy with all the pianos.’ You went up and visited Steve way up somewhere in far Northern California, right?

ANDIE: That’s right. It’s not too far from Gerlach over the mountain and under the woods. He lives in a Northern California town. I went up to visit him and recorded him.

Steve Heck is an artist and his medium is pianos. He experienced a fire. He brought his pianos out to the desert and also kind of helped us get our heads around all the big heavy things that were starting to move back and forth on and off that playa.

His story is about how he ended up lost in the desert, wandering alone, for a dark night of the soul.

STEVE HECK: Basically I made instruments out of stacking pianos two or three high in the shape of a circle, and the keys were now drumsticks. And then I would turn loose and people would beat the hell out of the thing, you know. I called them piano bells. At that time I did a piece for Lollapalooza, and I did a couple pieces for the Grateful Dead.

I was doing that before my house burned down with just any junk pianos that could not, the strings were good, but the mechanics of them were ruined. But they still were beautiful harps and they made just about any sound in the world.

When my house burned down, I had this pile of pianos and I just couldn’t throw them away. John Law was my friend and I asked him, I said, “So this Burning Man thing, can I just show up and do a piece?” He said, “Sure.”

So I decided to take 88 pianos, like 88 keys on a piano, and make the largest piano bell I ever made. And if you were to try to make one of these things in the city, like 88 pianos and start talking about 40 feet in diameter. I mean, the thing would be right in your face. You couldn’t fathom it. But when I went to the desert, I made sure that I went a couple miles out of Burning Man, and I built this thing.

You know, when you’re in the desert, you think something’s a hundred yards away, and it’s five miles away. So when people would get to this thing, they’d walk and walk, and suddenly they would just be standing under this giant tower. And I had a bar inside, and everybody, for that whole week, they beat the hell out of that thing, and there was not a sound you couldn’t hear. I mean, it sounded like crying, laughing, people would start sending messages to each other from the other side, like smoke signals and stuff like that.

And then when all the strings were finally gone —and that was a blessed moment cause believe me, listening to that every day for a week— I burned it.

When you burn a piano, there’s a soundboard, it’s a quarter inch thick and it’s Norwegian pine. And so once that accelerates, then the rest of the piano, which is usually made out of oak or maple or something like that, turns into like a charcoal briquette. So it’ll keep its shape, but it’ll cook just like a briquette. And once one lights, then three will light and it just go off. And then the plates are covered with, their gold colored, but they’re covered with zinc, so when that ignites a bright white ball comes out with blue light out of it. And I always referred to that as the soul of the piano. So when you’re sitting there watching 88 of these things just pop off like that, you know.

Nobody paid me to do this. I cleaned up my own mess. I brought all my own stuff. And I did it without any machines. I had to use two big boxes that I would get it onto one box and I’d pick it up and I’d put another box and I would just lever it.

So that was my first year.

The first day I got there, it was a very long trip and I’d never been to the desert before. I didn’t look at the paper to “How do you get to Burning Man? I didn’t look any of that. I had a truck with a platform over the driver’s thing like that. I had a couch up there, and I put a stick between my gas pedal and my seat, and me and my buddy climbed up on top of the truck. He had a rope and I had a rope and that’s how we steered it. That’s when the playa was so flat. And we drove around for like three hours before we found the site, you know, just driving across the desert, sitting on top of this truck. It was amazing. I’d never seen anything like that.

So when we finally got to camp, John Law and a bunch of people came out and said, “Hey, we’re going to town and we’re going to go to the Fly Hot Springs first,” which was unbelievable. And then we were going to go to town.

And I had been up for a long time, you know, I’d driven this truck full of pianos up there. And I had eventually had six loads that came up to bring my pianos. But I drove the first load. So we went to town and he goes, “Okay, now that I fed you guys, you all got to help me load these trailers.”

And I had, I just had a conniption. I was just like, “I just moved 25 pianos! I just took them off my truck!” And I, so I, I just, I said, “Fuck it. I’m walking back to camp.” I had no idea… anything about anything!

So I’m walking out of Gerlach. I get picked up by a pickup truck, finally, and they’re going to take me to the, there was a gate which was like five miles before Burning Man. And I get in the back of this pickup truck and it starts to rain. And it’s raining so hard I feel like I’m being shot with 22 bullets. I mean, I’m just, I’m sitting in the back of this truck going like, “Oh!” And this wind comes up and I get out and I’m like, “This is… There’s nothing worse than what I just experienced!”

So I start walking out into the desert, and I could see the lights and stuff like that, but I had no idea that the altitude changes up to 20 feet. You go across the playa, you can be walking and you don’t know that you’re actually walking down. And so I looked up, all of a sudden Burning Man kept disappearing. I can’t see where I came from. I can’t see where I’m going. And I was really fit back then, so I saw a car, I started running to this car. The car was like five miles away. I thought it was like, and that’s just the whole thing about the size of the piano bell being so, you know…

So I chased cars and ran all the way from eight o’clock that night till one o’clock the next day. And I had no water. I had these boots on I’d never wore before. And I took them off for a minute and my feet swelled up so I couldn’t put them back on. So I was wearing a wife beater. I had shorts. I had $300 cash in my pocket and a knife. And I do exactly what you’re not supposed to do. I start heading for those lights out at the far end of the desert.

The whole night I’m running, I’m panicking, I’m screaming, I’m throwing fits. My feet are just like, I mean, there’s parts of that desert where it’s not soft anymore, just gravel, and I get to this one section where every three steps I took, the crust would break, and my feet would go through the sand, and the edge of it would rip my shins open.

And little did I know, at that point I was right next to Trego. There was water, there was trees, if I had known anything, I would say, “Oh look, there’s a group of trees, there’s a good chance there’s water there!” I didn’t know. That whole night I’m running around. I was trying to find the North star. I could not believe how many stars there were. I never, all the mountains, everything looked the same. And occasionally a dust storm would happen and I would be sitting on the ground with my shirt over my face. It was the most hellish fucking… and so that’s what I did.

So eventually, I’m walking across the desert. I’m finally going the right direction because the sun was coming up. I could see my shadow. And I’m like this limping thing, you know. I could see everybody going to Burning Man, I could see them on the desert. And I have my shirt on my hand and I would occasionally wave it. And eventually some people, they saw me, and they picked me up.

And then I couldn’t walk for two days. Then I built that sculpture barefoot because I couldn’t wear shoes. That was my first experience of going to the desert and building something at Burning Man. And I went back…

ANDIE: You went back because?!?!

STEVE HECK: I went back, well hell, I got, I got the respect… I don’t think I ever respected the power of our planet until that moment, just the vastness of it, the amazingness, and realizing that people live out here, and you can survive this shit if you have a brain in your head, which at that time I was just, it was just starting to form.

So I went back a couple of times and I ended up being the… I was a professional mover. It’s all I did. And I could see how they would take them, like two or three months to get off the desert. It was just a total shit show and there was no technique to it. And so I started doing their, clearing the desert, you know, by getting a group of people. “Hey everybody, everybody bust up in groups, get pallets, get stickers. Put all this stuff right there. Okay. We’ve got two semi trucks, I’ll go around the forklift. We’ll load these. And while one is going, the other one’s coming back.” I taught them how to do that. We could get off in two weeks that way.

ANDIE: And did you just jump in because you observed that it was not being done well?

STEVE HECK: Yeah. I really believed in it. At that point, I believed in the event and they didn’t have any shipping containers, and I knew where to get shipping containers, so I started getting them those shipping containers and, and those kind of things, because in my mind, I had somehow come to believe that it should be in a different place, like every two years, you know. Instead of burning up one little place, I figured, imagine if… people come from all over the world to go to it, so even if it went to a different place every year, maybe a different country. That would be amazing, ya know, to travel the world and put this party on all around the world. And then, you know, you use the materials that are available to make the stuff, all that stuff could be done on site. So I advocated all these things and they basically thought I was crazy.

When I first went, it was like 7,000 people and we had the drive-by shooting range, you know, and all that kind of stuff, and people were… they knew nobody was going to hold your hand. Anyone that went there knew that if they fucked up, they could die. And hardly anyone had RVs, it was all these crazy tents. And everybody really represented, their camps all represented. Everybody at least one night cooked a meal, and you could go around and everybody was… it was interesting.

And now, I don’t go anymore because there’s just too many damn people, too many damn RVs, and God, there’s so many cops now and all that stuff, you know? It used to be such an amazing thing, but good God.

I still think it’s a worthwhile event and it’s better than nothing, but it kinda went out the window for me. But I did meet some great people. I did have a… I went four times, but three years I made pieces of art that I could never make anywhere else.

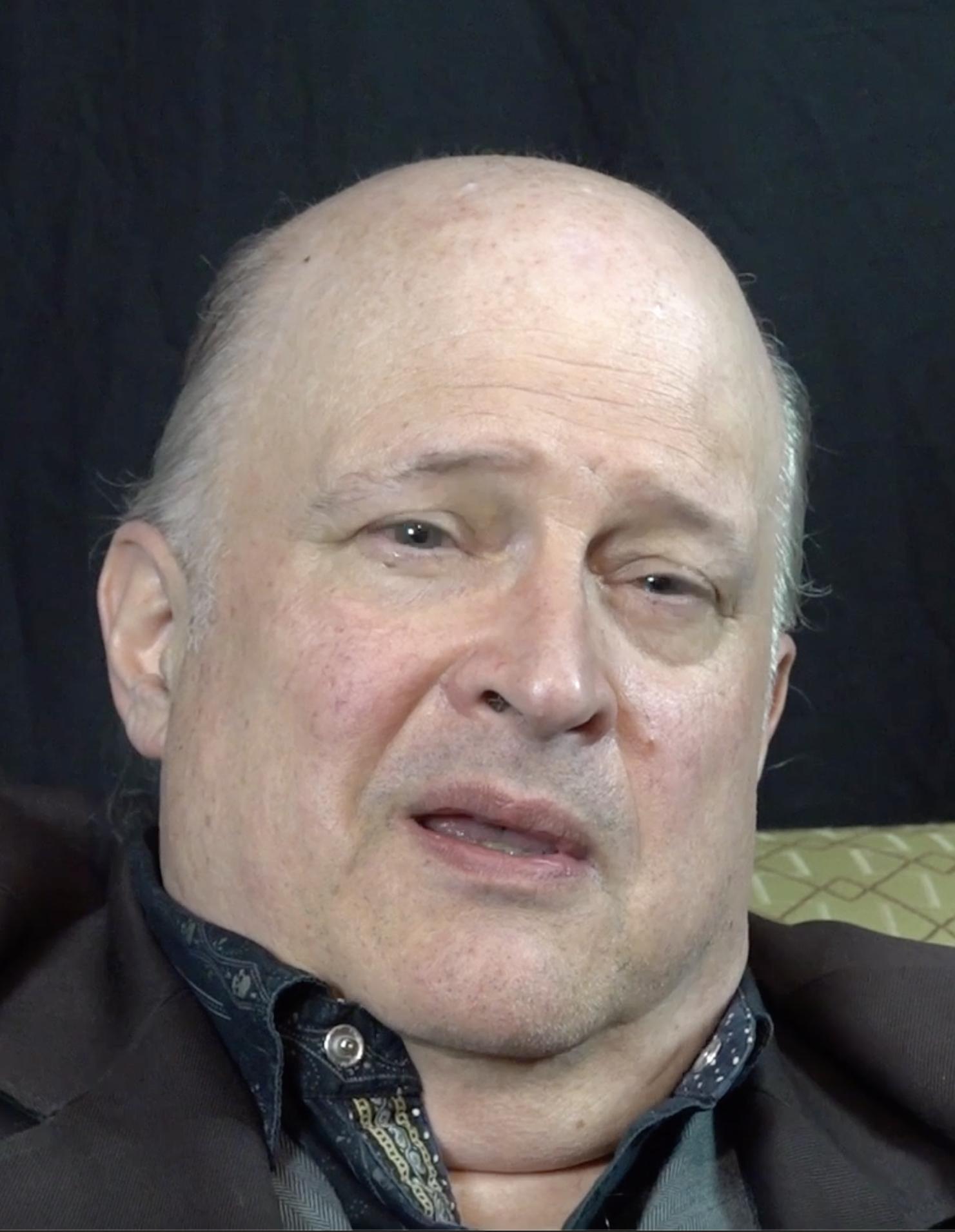

STUART: Hal Robins aka Dr. Hal, Dr. Halinel, is another huge figure in the Cacophony movement, lifelong Cacophonist, and also an Uber Pope of the Church of the Subgenius, all you Subgenii out there. He’s a long time host of the Black Rock City Fashion Show; beloved by radio and stage audiences around the Bay Area and beyond for his mellifluous voice. Hal can literally read the ingredients off of a cereal box and make you smile.

Also, he played the part of old Nick in the 1996 Helco video promoting the Helco Soul Debit Card. I’m sure we’ll manage to stick a link to that in the show notes, because you gotta see it.

ANDIE: I keep referring to Hal as the only guy who does remember not just the faces and what blew up and the places and all of that, but the names and the dates and without consulting any notes or journals. His mind is an awe inspiring place. I was so looking forward to spending some time with him and you could listen to him for hours, right?

STUART: Yeah. His memory is insane. He will recite The Rime of the Ancient Mariner from memory and actually make a great dramatic presentation of it, and other I’m sure other epic poetry too.

ANDIE: Yes. That is high entertainment in the city of San Francisco.

STUART: Yes.

ANDIE: His bio; he says he’s a multi-talented renaissance man, and that’s so true. He’s been a radio show host. He’s an expert in so many subjects. He’s an amazing painter, artist. He’s a performer. He’s made children’s books about, like, dinosaurs. And he does voiceover work for video games. So, like, Mr. Fascinating Man in a fascinating moment in time, out there in the desert. Here’s what he had to say.

HAL ROBINS: I like the inventiveness. I like the surprise of seeing what people create. That is always a delightful part. Although if you have a really nice camp, you want to sit there for a while and have other people come and visit you, the passing parade of people and vehicles is fun to watch from any part of Burning Man.

It’s also nice that it’s flat, and so if you have a bicycle, which is essential, you can really enjoy riding the bicycle.

ANDIE: We don’t spend nearly enough time just perambulating around the world and meeting people.

HAL ROBINS: Well, when you do, you run into adventures. A lot of my time, unfortunately, is spent on looking for people, riding around on the bicycle, and invariably you never find the ones you’re looking for, but you always find others who you also knew, who you weren’t looking for, or they find you.

ANDIE: Do you have any rituals that you have to do, just a personal thing that you do every year when you’re out there?

HAL ROBINS: None that I can think of except to hit my performance points of the Fashion Show and the TV car. In the past, I have happened on things that were going on and been asked to be a part of them, like Davy Normal’s play one year, the one called The Secrets of Uranus.

Did you see it?

ANDIE: I did see that.

HAL ROBINS: Yeah. I thought that was wonderful. I was very happy and pleased to be a part of that. It was the year when the fire cannons were out there, and just as a coincidence as we finished the show at the climax, all the fire cannons went off. So it had a lovely conclusion.

In fact, my lines concluded the show, and I was horrified to discover, moments before I had to speak them, that I had not been given a microphone, and I managed to run out of the thing looking for a microphone, and the person playing Satan had the mic and said, “Come on up here, Dr. Hal,” Thank God, the devil saved me, you know. I jumped up, I used his microphone, I said my lines, the show ended, the fire cannons went off. And the music was so good, the girls singing were so melodic, and the song was so beautiful. It was a great antidote to the usual throb of music that’s heard at Burning Man.

Now, speaking of that, this is a sound that you could not hear anywhere else on earth. When you’re standing in the middle of the playa and all this sound comes sweeping across from the entire crescent of Burning Man, combining into a susurrus of sound, that says Burning Man to me very strongly. And it’s one that I never mind hearing.

I just mind when the disco cars come so close that it’s impossible to speak. And often the TV Car is riding around trying to find a place where it’s not so noisy so we can do our show. We do pretty well by visiting all the porta-potty areas where we are always going to have an audience and where the disco cars tend not to hang out except when they make a brief stop.

ANDIE: That’s good advice. Find the interaction by the porta-potties.

HAL ROBINS: Yeah.

ANDIE: Why does Burning Man matter in the world?

HAL ROBINS: Well, it’s a development. It’s part of the growth of people. And in recreation, we are creative, and we’re doing things. We are genuinely creative. The word creative has been taken captive recently, but it is necessary to create to get along out there. And this is what humans do and do very well.

Society at the moment is convincing people that only professional singers can sing, only professional actors can act, only professionals can make art, music, and so forth. But these are all human abilities. To some extent, everybody can do that. Burning Man gives that a chance to happen.

People are actually capable of singing, but they believe that they are not because they are not the professional singers that they see on social media or movies or TV. Burning Man takes away that particular background and you find that you are more capable than you thought you were.

And it’s, of course, pleasant to find that out because art is an anodyne. Art is therapy. The reason people make art is because that makes life better. And if you are wounded psychically, the art will heal the wound.

That’s why they say the artist must suffer. It’s not because it’s good for artists to suffer, but the suffering generates the art. And, we’re all kind of suffering out there, dealing with the hostile environment, and it somehow works in that strange way.

ANDIE: The environment is an interesting element to it because community is created by that shared strife, right? If your neighbor’s tent is falling over you rush over to help him and that builds community. And yet we have this Regional Network where Burning Man is happening in other places. Have you attended any regional events?

HAL ROBINS: No, I never have because I go to actual Burning Man. Nor did I go to the non-official Burning Man which I thought was quite interesting because they observed the whole thing; they formed the ring, the structure with the esplanade and so on. This I heard about, I wasn’t actually there. The pandemic stopped and scrambled everything. But it shows that people want it to happen. And if they can’t get there, they’ll have one of their own, and that shows there must be something good about it because they are imitating it, because they’re doing it.

C.S. Lewis said that it’s very difficult to tell whether a work of literature is good or not, but one way is, if there are people who will passionately defend it, and who get something out of it, then there must be something in it that they’re getting something out of.

ANDIE: So after all this time, it’s still fresh to the newcomer and still fresh to you, it sounds like.

HAL ROBINS: People come, you could divide their reactions into two. It’s either, “Get me out of here. This is horrible. This is a nightmare. How can you be doing it? But I can’t get out, you know, if I get out, I can’t come back, you know, what’ll I do?”

Or the reaction is, “Hmm, well, I thought this was bad, but it’s actually kind of good, but next year I’m going to bring a so and so and a so and so.” And they start making their plans. And now they are part of it. As I tell people on BMIR, nobody is ever left behind.

For a while, I was on BMIR connecting people with rides. I always liked to do that. And at times, when everybody is leaving, then I have a great captive audience, because all they’re doing is sitting there in the pulse system trying to get off playa, and they have to have the radio on, and so they are at my mercy and they have to listen to me.

ANDIE: I’m often the DJ on Sunday afternoons.

HAL ROBINS: It’s fun, isn’t it?

ANDIE: And people are stopping by looking for a ride and they do, they just sit there, and sit there.

HAL ROBINS: Well, we connect them with a ride. It’s amazing what rides they have. Once a bus came and a woman who looked like Marilyn Monroe, she was collecting people to drive them off of the playa, and we were able to announce that. It’s good to make people happy.

ANDIE: It’s kind of a place where a lot of magic things happen almost unseemingly so. Do you agree with that? And if so, to what do you attribute it?

HAL ROBINS: I do agree because our tools, our devices, get in the way of connections that are somatic, that are part of the human ability, that we forget we have, and then we’re forced to use them, and we feel delight in that we are able to use them.

ANDIE: That’s a great way to put it.

How do you see Burning Man evolving in the future in the face of everything that humanity faces right now?

HAL ROBINS: Well, I don’t think Burning Man gets a pass! Outside Burning Man, we’re all in the same predicament. There are those like Grover Norquist who go there and think that Burning Man represents the libertarian future. What this means is that you can project any social idea on Burning Man because it is a community. You could call it socialist or communist, I don’t think you could call it reactionary. But there are those elements of it which are reactive against things that we have to endure in the so-called default world.

However, learning to live in adversity, being able to use a small amount of water, things like that, these are good things to learn. I’m shaving out of a little cup of water this big. I’m not splashing gallons around in a porcelain bathroom. You have to learn these methods.

ANDIE: And when all your trash sits at your feet all week unless you pick it up, there’s a valuable lesson in that.

HAL ROBINS: That’s right. Well, you have to have a plan to get rid of it.

ANDIE: You think that people take that kind of transformation home with them once learned?

HAL ROBINS: It is always somewhat present. The pressures of the interaction of society push it to the background, but you’ll never forget it. And the more that you go, the more it becomes a part of you.

ANDIE: You think you’ll continue to go until you can’t anymore?

HAL ROBINS: Well, I’ve always gone because they wanted me to be there. So it would be terrible not to go if they want me to be there. And I never really know, you know, maybe this will be the year they don’t want me to be there. But as long as they do, I will go and I will do absolutely everything I can to make it good for everyone else.

ANDIE: What do you wish people understood about how it used to be?

HAL ROBINS: That it was spontaneous; that it was not official; that it was part of a private group; that it had no other agenda than its own; that it’s not a drug soaked rave exclusively; that there’s no way to understand it except by doing it.

ANDIE: Is there anything about Burning Man that I didn’t ask you yet?

HAL ROBINS: Well, there could be, because so much happens out there. You’re not just going to do one thing there. You’re going to do a lot of things. You’ll do more than you thought yourself capable of, and you’ll do a lot of things you never planned to do, of necessity. You will have to do them, and that will feel, it will feel good.

ANDIE: And have you seen movies and content about Burning Man that you think gets it right? Simpsons episodes notwithstanding, perhaps?

HAL ROBINS: Oh, I felt the Simpsons episode was quite good, especially when they put up their tent and it blew away and became a tiny rectangle in the sky. I think everyone’s had that experience. But no movie can really, it’s a cliché, but the movie is one dimension. There’s nothing like being surrounded in Sense-O-Round and Vista-Vision and Cinema-Scope and Smell-O-Vision, and everything which Burning Man provides.

ANDIE: And Dust-O-Vision.

HAL ROBINS: And Dust-O-Vision. Yes, there is that.

STUART: Yeah, that’s about all we got for this time around.

Andie, I can’t thank you enough. Keep collecting those stories. This is truly important work.

ANDIE: So many more to come!

STUART: This really, really does matter.

ANDIE: I have had so much fun becoming this historian. It’s an honor. I’ll keep on peeling the onion of Burning Man until I get to the juicy center.

STUART: If there is in fact a center. Yes.

Burning Man LIVE is a nonprofit production of the nonprofit Burning Man Project brought to you as an unconditional gift, no strings attached, from the Philosophical Center. You can download it, stream it for free from all the usual podcast places, now including the YouTubes along with Apple, Spotify, Google, blah, blah, all the other places where you get podcasts. Or for an even more thoroughly decommodified experience, you can get it straight from the source at burningman.org/podcast, where you will also find detailed show notes, transcripts, all kinds of goodies in there.

And if you’re in the mood, it’s immediately adjacent to donate.burningman.org, which is how we keep the lights on around here.

Thanks to everyone who made this episode possible, especially Actiongrl Andie Grace, Vav Michael Vav, Tyler Burger, DJ Toil, kbot, Alliesaurus, and the whole podcast zoo crew, including Vav’s cat.

Uh, thanks to Maid Marian and Harley and Danger Ranger for supporting the Oral History Project. We couldn’t really do it without their notes.

And to all of you for listening, subscribing, liking, reviewing, and sharing the Burning Man LIVE love. I’m your executive producer, Stuart. Thanks, Larry.

Opinions expressed here are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views of Burning Man Project.

more

Andie Grace

Andie Grace Candace Locklear

Candace Locklear Chris Radcliffe

Chris Radcliffe Dr Hal Robins

Dr Hal Robins kbot

kbot Steve Heck

Steve Heck Stuart Mangrum

Stuart Mangrum Summer Burkes

Summer Burkes