His huge steel sculptures have graced Black Rock City for decades, then found forever homes in cities, festivals, and private collections around the world.

Hear veteran structural sculptor Michael Christian go deep and wide about his Burning Man art, from a tree of bones to a 65-foot tall tower.

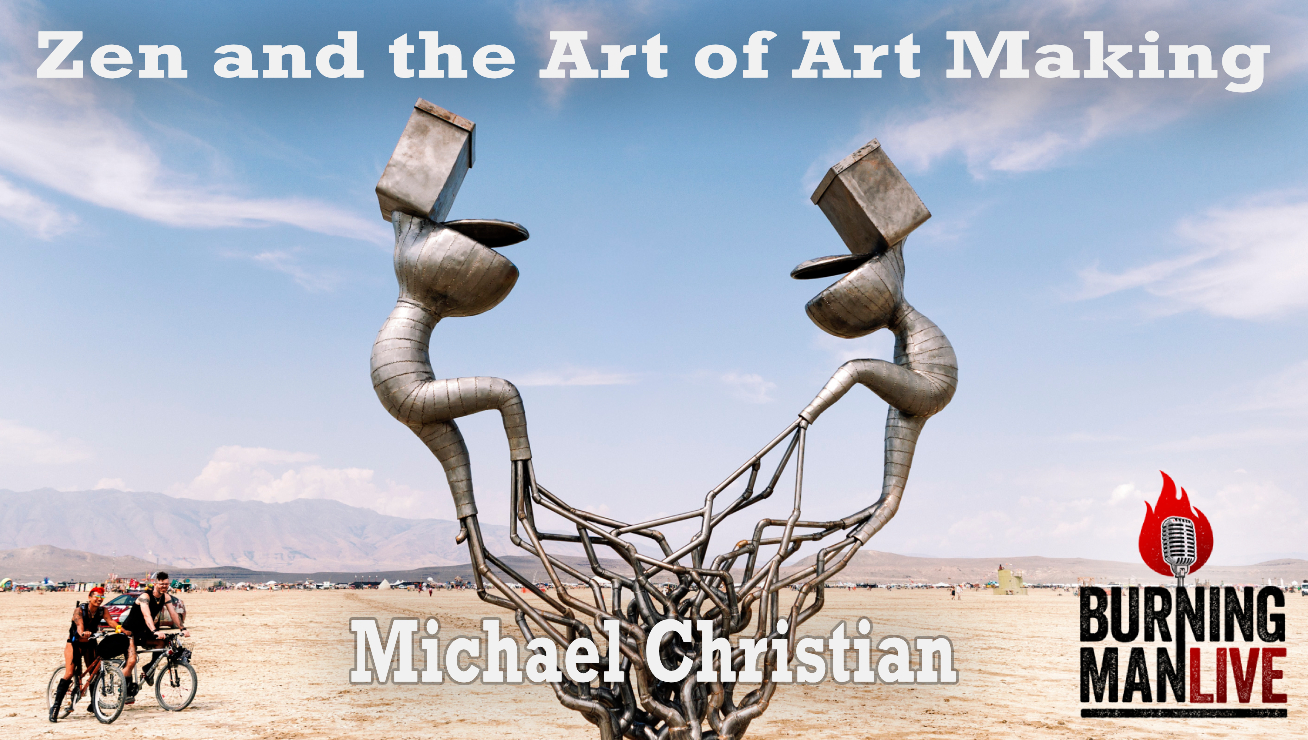

He shares about his installation “Down the Drain,” a commentary on human alignment or misalignment… or maybe it’s about toilets blowing kisses at each other!

He talks with Stuart about the shift from a “lone artist” mindset to community collaboration, and how to get everything done despite a storm or a lost box of bolts.

They tinker with the qualities of hubris and humility. They get real about why they keep returning to the collective happening in the dust.

- How does Michael follow intuition more than a thesis?

- How does he discover the meaning of his art only after he has built it?

- How did ‘out of the box’ thinking become a 30 year career?

These questions are answered with more questions in this episode right here.

Transcript

MICHAEL:

I want to make it, but it’s ultimately making it to share with other people. You get to display it and share it with all these people, and join the other people that are doing the same thing. Burning Man’s pretty cool for that. There’s a lot of people that build things and they get excited. It’s like the time of the year when everybody’s working on projects and you’re sharing information, energy, know-how, with all the other communities that are there, and with the sole intention of going out and sharing.

And you get excited like, oh, so what are they building? And what are we building? And we’re part of a bigger community of people that are doing things to share with other people.

Meet the people who make Burning Man happen around the world the dreamers and doers the artists freaks and fools (a serious amount of silliness) Burning Man LIVE

STUART:

Hello. Hello. You’re on the air.

MICHAEL:

Hi there, viewers. Welcome to the podcast.

STUART:

Out there in Streamy land.

MICHAEL:

Welcome to stream land.

STUART:

Hello out there in Camp Envy, Camp FOMO, all you camps who aren’t out here enjoying the beautiful bounty of nature with its gusty winds, its beautiful puffy clouds, its gray skies, its occasional dump of rain.

It is Burning Man LIVE. We are actually live again from the fabulous playa of the Black Rock Desert from Black Rock City 2025.

I am your host, Stuart Mangrum, and I’m here with a longtime Burning Man artist, a great contributor to this community over a lot of years that I’ve really wanted to have a conversation with for quite a while: Michael Christian.

How are you doing?

MICHAEL:

Fantastic on this mud morning, beautiful mud morning.

STUART:

So I’m going to start with the right now here in the mud. What are you up to this year?

MICHAEL:

Well, I installed the sculpture Monday during a reprieve of the weather, a piece called many things; Down the Drain is the official title of the sculpture.

STUART:

Tell us more about that. I understand that some plumbing parts were used and abused.

MICHAEL:

Used and abused? Yes. It originated from a drawing I had done several years about these two toilets in conversation with all of their mangled plumbing parts connecting, just a worthless conversation of who gets control of the sewage. It sort of evolved into a sculpture that is a single drain going down into a drain cover. Pretty symbolic of: we all go to the same place in the end, no matter what you squabble about. They’re all interconnected and entangled and kind of squabbling or actually somebody came through and was saying they were blowing kisses. Which is totally true. But in the end, you’re all in the same poop no matter what you do, so…

I’ve had much better analysis from people who walk up, especially kids. Kids always give the best observations. But, I always loved the title that other people give, so it’s really hard title a piece, and especially when you’re building something, I don’t really know what it’s about sometimes till after, but during the course of building something, you kind of discover you have an idea in the beginning, but it really is just an idea. And I really like the process of building because it’s always a new adventure and you discover what it’s about and what you’re doing in the process.

STUART:

Start with an idea, not a thesis statement.

MICHAEL:

Definitely not. If I am, it’s a delusion because it’s always something different. I could say it’s about this and this and that, and then in the end, it could be about my abandonment issues or something, I don’t know. It’s always funny. It’s a left / right brain kind of thing. The logic side says we need a title. It needs to be about something. And then the intuitive side takes over and it’s like, well, here’s what it’s really going to be about. And in the end, you get to a place that you didn’t really see clearly in the beginning, but it becomes apparent towards the end.

STUART:

Yeah, our true motives are always a little opaque to us unless we’re lying to ourselves, right?

MICHAEL:

100%.

STUART:

So tell me more about the piece. What does it look like if I stumble across this?

MICHAEL:

It’s probably 14 feet tall, 20 feet wide, a large drain moving up to a mangled, organic, twisting pipes that come up to two different toilets that are facing up to each other. And they actually don’t look directly at each other, which is what arguments are about anyway. You don’t quite clearly see the other person. If you did, you probably wouldn’t be arguing.

It was fun. It was fun to build. I didn’t, I just started putting pieces of plumbing, sewage pipe together and then developed it as I went. And I thought it was going to be different looking, but it turned out exactly how it should be. I enjoy making these more intimate pieces as opposed to earlier years when you build large things. Not to say those aren’t fun.

Yeah, there’s something fun about building the large pieces, because it’s part of a community of people and you get to work with other, other folks that have different ideas than your own, which is positive and negative. It takes you to places that you wouldn’t go, but also sometimes takes you to places you don’t necessarily want to go.

STUART:

Yeah, you’ve been collaborating with a lot of interesting people over the years and working with a lot of interesting found materials, plumbing parts is one, but the first piece of yours that I remember, it might have been the first one out here, was The Bone Tree?

MICHAEL:

Yeah. Dana Albany introduced me to Larry, I think, in that way. They came by… I had worked with bones when I lived in Texas, and they approached me with the idea that they had bones on the property and asked if I would come out and build something. And it’s funny, when they asked, I was kind of hesitant because I hadn’t really… I was doing the gallery museum angle.

STUART:

Fine art.

MICHAEL:

Fine art. Yes. My degree, my big fucking achievement, my BFA, I was in that world. And so when they approached me about building something out of bones, I was very reticent to do it because I was like, I don’t know. I don’t really do festivals. It seemed pretty lowbrow, but I had to reflect that you want to support me financially, to build something that I would want to build, and then thousands of people would see it, and I had to reflect like, that kind of sounds like what I want to do. You know, that’s the whole spirit of what I want to contribute to. And who knew I would do it for another 25 years with the organization.

But, yeah, we didn’t know. We showed up and just built the tower of bones, and it was going to be four towers, and it became an archway, like 30 feet tall, over a couple of days.

And it was in the spirit of how I like to do things: just discover and enjoy the process. Really it’s all about the process for me of building and discovering as you go.

STUART:

Yeah, Dana has been on the program before and she talks about that as really a starting point for her, as an artist.

MICHAEL:

The bones?

STUART:

Yeah. And I think with love and respect for you.

MICHAEL:

Oh, it was great to work with her. And funny enough, the next year we did a project, the Nebulous Entity, and…

STUART:

Yeah. What was that?

MICHAEL:

I originally agreed to do the Nebulous Entity. I said, I will build it, but I will not do anything with it after. And there was no plan, and it was left here. And it was left here and it was burnt. Somebody set fire to it. And there was a shell of it, and then brought the shell back to my shop, and we used the shell to build the Bone Tree with some remaining bones from the bone arch. And then she collected a lot of bones. And then down in Hunters Point, I was there to support how I could, but it’s always been funny because I look at the Bone Tree and I’m like, oh, look, there’s the Nebulous Entity, wheels and armature and so forth.

STUART:

I think it’s still out there at Fly Ranch.

MICHAEL:

It probably is!

STUART:

Nebulous Entity, Larry liked it so she made that the theme that year.

MICHAEL:

I know! That was…

And that was really amazing. That was the first introduction to working with community. I’d always been in the artists in the studio, mind frame and, and toiling away as the artist struggling. And I kind of backed into the community aspect of it that really took me off guard, really empowered me in a way that I wasn’t expecting, and surrendered to the collective process of the group of people building something, and it’s magical.

There were a lot of amazing people that went on to do other projects on their own in the desert as well. Even Crimson was down there wrapping plastic in newspaper and contributing to the thing. It was early days, the event, so it wasn’t it was still sort of amorphous or it was still a process. It was uncertain.

We didn’t know that there would be another year. It was the first time I’d ever been a part of a community project. I was kind of hooked on it and the whole process.

STUART:

Larry Harvey is to talk about how organizational leadership was very different from creative leadership that you needed to have. Maybe somebody at the helm, making the decisions, right, and breaking the ties.

MICHAEL:

And it was a different role to be kind of a director, because I would give people as much space to do what they do, and they would invite them to be creative, and then you would have to kind of steer that back into a cohesive project. And sometimes you would have to redo the work that somebody would do to make it work as a project.

So it’s a different role. But some really amazing people that came; engineers, designers, there was a sound engineer that created the soundtrack. This interactive piece that was really amazing. The early days, you know, like MIT people, lighting engineers, mechanical engineers. And people would come and volunteers for some, I’d ever have somebody show up with high skills that wanted to contribute. And I’m like, wow, this is pretty cool.

And everything happened spontaneously. People would show up when you need them to. It was the first time I’d been in that field of collective happening, where things just took care of themselves. You need a thing. They would show up.

A guy showed up on a Harley one day. He was like, “I heard you need a welder,” structure welder. And I’m like, “Yeah, we do!” I was early days welding. I was never… I knew how to weld, but not half inch plate steel construction, you know. Lots of occurrences like that happened and they continued to happen in all the projects that evolved.

And in the spirit of collective happenings, I really got into the idea of this interactive collective art, and not being just the artist. It was a different kind of role, but so rewarding because it wasn’t just me building something, it was a group of people and a lot of relationships that I still have today came out of that, and other people that met on the projects with me formed relationships, and it was pretty addictive.

STUART:

It is amazing how overqualified people come out and volunteer for jobs that you would think that wouldn’t be that interesting. When rocket scientists come out, “I want to participate in an art project,” what do you think is behind that? Is it just that they’re lacking, well, creativity in their lives?

MICHAEL:

I would approach engineers, or some of the engineers, and their first response was, “No, you can’t do that.” And then they think about it and then like, “Well, I have an idea.” Yeah. And then we’ll come back and they’ll present something because it’s out of the box for them. They’re used to building squares and different designs that are in a pretty limited range. They would get them out of the box, so they would be like, “This is exciting and fun.”

I felt very blessed. And I would always give respect to that, honor the collective because my name’s on it, but there’s no way that I could have ever built any of those pieces without the support and generosity and energy and the hands that go into doing that. It wasn’t just me.

And I get to soak up all of the information and knowledge and knowhow from all the people that were working as well. So at this point, I’m all parts of it. I’m the design. I’m the engineering. I’m the fabrication. I’m the transportation and the installation. And I think that’s how I would be able to make a living at it for 25, 30 years, because I’m doing all the things. And that’s in large part because of all the people that I worked with. And you’re taking notes and absorbing, you know, the information about engineering and how to build and weight loads and capacity, and the power of the triangle and tetrahedrons, you know, and electricity and wiring. I have worked with some very talented people.

STUART:

Let’s talk more about making a living, because anytime I talk with a long time Burning Man artist who’s managed to make a living in the world… I’m just curious, career wise, from, you know, art school to where you are now: How have you paid the bills?

MICHAEL:

Yeah, I remember there a moment when I didn’t say yes to every project, and I would start to be a little more selective, but I kind of backed into it. It wasn’t… Like I said, I was coming from fine arts, and I never imagined being in festivals or doing events because it just didn’t… It was a little outside of the box. But one of the reasons I came to Burning Man in the first place was to get outside of that. Before I’d been doing some installations in spaces that were about the interactivity of like, you could touch the things and the walls and you could smell and you could hear. And there were installations you walk through and there were sculptures, but it was more of an environment that you experienced and the limitations of galleries and, official, you know, whatever they, they know you can’t touch or know you can’t interact with.

So I kind of backed into doing festivals. And then as we did more festivals and they were like, well, can you bring this to our festival? So I took a piece to Coachella for 8 or 9 years, and then another festival and then Electric Daisy Carnival or Live Nation or whatever. And then I think at the peak I did like 10 or 15 events in a year.

STUART:

Wow.

MICHAEL:

When you’re hiring people, but then you get further from the actual source of making, you’re more producing and it’s like, okay, I need to scale this back so that I can actually build. And then after a while the people would see the pieces and you could sell some of the pieces because they’re yours.

But then other festivals, “But we want our own commissions, we want to build for this.” And so then you’re commissioning 3 or 4 pieces a year and yeah, you kind of backed into making them.

I think it was in the right place at the right time. With just the burgeoning festival happening and the late ‘90s, early 2000, I was never planning that out.

And at some point you kind of laugh because you’re like, oh, I have a career. I’ve been doing this for a while. I guess I have a career. It was never how I imagined it.

STUART:

Could any of us have planned any of this?

MICHAEL:

If I would have planned that, it would have failed. Right there is. I mean, that’s kind of the process of building things that I try not to have an idea. I always know if I’m getting frustrated, it’s because I’m resisting the change that needs to happen in the process. If I let go of that…

We were building something and I had an idea of like, bend these parts and we’ll put them into the piece. And we could not get them to bend the way that I wanted them to. And I’m like, well, maybe they look better the way that they’re happening. And it turned out to be a beautiful… It was this piece called Void, and it created this kind of orb with the way that the mangled pieces happened. And it wasn’t how I had intended to. But I was really frustrated.

And then you’re like, well, surrender. This is what it is. This is what it has to be, and incorporate that into the process of building.

And Larry and I had a great relationship because I really appreciated that he respected that process of, “Here. I have this idea A, but it could be P Q R, it could be Z, by the time you get to the end.” And he understood that that was part of the creative process and supported that.

STUART:

Supporting artists, I think, was his favorite part of the job. He didn’t really like the guru part, but he loved to work with and foster artists coming up and that. Now look at us. I know how many people I know touched by that, right?

MICHAEL:

Yeah. I was just talking to Marian last night, and she was mentioning Larry had an old piece of mine. It was this hairy claw talon that I had made from years ago when I was working in fiberglass and found objects, and it was hanging in his house above the sink. I mean, it was five foot long. It was a big thing. And he loved it. And I was just like so appreciative that he would support that way. But yeah, he would always get excited when we’d talk about it.

Funny enough, that Nebulous Entity, the year we built that, we were late. During that time, we’d build during the week and you would finish on Tuesday or Wednesday, but this was like Thursday or Friday. And he’s like, “It’s got to go.” And I remember yelling at him, “It’s not done yet Get out of here. You don’t know. I’m an artist,” and really some serious hate towards his direction. But we brought it in and it was there. But then the next year, they were like, “Hey, we’d like you to put a piece in the keyhole.” I was like, okay, this is not your normal relationship. This is like family.

STUART:

So how did you find out about Burning Man?

MICHAEL:

It was an underground thing. I went in ‘96.

STUART:

Oh, okay.

MICHAEL:

…for HELCO, and like most people, was blown away and changed. I thought I was one thing. Came out the other side realizing I wasn’t that thing and needed to… It was a big directional change, impactful. But it was still just a gathering. It was chaos. There were no streets. There was no structure or order. Didn’t need to be. But that year, as you know, unfortunately, there were accidents, and then changes had to be made as it was growing. I think there were 5000 people, maybe.

STUART:

Something like that.

MICHAEL:

Not a lot, but it had a big impact on me. But again, was there going to be another one? Who knew?

STUART:

Not the first existential crisis.

MICHAEL:

And it was very uncertain.

STUART:

Uncertainty.

MICHAEL:

Or anything that was going to continue.

I think in large part the coinciding with the explosion of internet and online communities. It continued after the event, outside of the event. But before that, it might have just fizzled. It’s like, there’s this great thing we did, but I think it was growing, so…

Mr. Vav over here, was part of Happyland. It was one of the first groups that I was a part of.

VAV:

Yeah. Happyland. Wild times.

MICHAEL:

Haha. Yep!

STUART:

When I first joined the organization, or “‘the organization’” in triple air quotes for extra irony, uh, we were still sending out paper newsletters in the year-round, right? And then the first commercial browsers came out and the first online discussion groups on The Well. Eric Payoul put together a list server.

VAV:

Yeah. Eric and Rachel, the Diox List.

STUART:

That’s really why it grew so fast from ‘94 to ‘97. Too fast, some would say. John Law is still pissed at me for that, for ruining Burning Man by bringing too many people.

MICHAEL:

But oh yeah, so many things are ruined!

STUART:

But you can’t stop it. You can’t put the lid back on that, right? Oh, it’s just going to keep coming out, right?

MICHAEL:

Putting your finger in the dam. No. Once it started, it was going. They guided it, but I mean now it just kept expanding and expanding and it grew quite a bit.

‘97, I think, was the year that that media crunch came in.

STUART:

Yeah, ‘96 was the first, was the WIRED Magazine cover story that kind of blew the doors off, right?

MICHAEL:

Yeah. And then they were all there for ‘97, they came in force. I remember the swarm of media coverage.

STUART:

In that wacky, scrubby edge of the Hualapai Playa on Fly Ranch.

MICHAEL:

I remember doing an interview for ABC Nightline or something, and I thought for sure they would not use it because I was not friendly to them. It was like, “Why did you do this, build this?” And I was like, “Because!” You know, or “What brought you here back to Burning Man?” And I was like, “That brown truck.” And actually, they had a clip of me and I think they did the overdub. They were like, “Michael Christian doing art for art’s sake,” and just cut out, and talked over me building.

STUART:

“Let’s just rework that story!”

MICHAEL:

Yeah, yeah, but hauling around bones and building this thing. But yeah, that was a big introduction to media for me and the event, and a little change from what I had been prior to where things were pure chaos.

I really had enlightening experiences. At the time, I remember I was reading a book called Crowds and Power by Elias Canetti, and it was discussing the dynamics of crowds and how you transformed, and you lose yourself and you change, and how things would grow and expand.

And the beauty of that, at that moment, at that event, where all the people would gather like fire energy that’s happening like, but there was nothing to quell it, to say stop. So it just dissipated. And then it would form somewhere else and grow and expand and then contract. It didn’t have purpose and as soon as you resist it or say, contain it, then it’s like, “Fuck you, we have purpose. We’re going to fight against you!” But there was no fight. It was just like, “We’re going to explode things.” And then it was like, “Okay, what’s next?” There was a car. I remember I woke up that morning and there was a car that burned outside of my tent, and.

STUART:

There was a lot of shit burned.

MICHAEL:

Yeah, I was like: I missed that. How did that happen?

STUART:

The organization collapsed, right? So many people quit that they had to really, really build it all from the ground up all over again. Yeah, it’s funny, I tell it: from the participants point of view. It was awesome. From the organizational point of view of the. Holy shit.

MICHAEL:

Props to the organizers or the people involved that have kept it. I know a lot of people were pissed because it changed, but it had to, you know, to continue. It couldn’t exist. You can’t have chaos at that level.

STUART:

Exactly. Yeah. Anarchy works in small groups.

MICHAEL:

Yeah. And it was beautiful and I loved every minute of it. But some change was needed. And with that you’re kind of like, oh my God, not more, you know, but that’s how it works. It was interesting to see the process from it being that anarchy, chaos, fire, and we’re throwing rocks and sticks at each other to streets, to civic departments, to DPW to like, oh, we’re having housing development to a large city and just in that short evolution of a town, a frontier town to a metropolitan city and all the things that go with it.

And so it’s so big now, you there’s so when people would say, what is Burning Man? And like, what is New York City?

STUART:

Right. Well, it’s not that big, but it’s not the same.

MICHAEL:

Stretching.

STUART:

Santa Fe, New Mexico.

MICHAEL:

Santa Fe, right. I’m stretching that obviously. But it’s just so many things you could do. There’s so many people that have a great time. So many people have a shitty time. So Burning Man can be shitty, but it can also be amazing and transformative.

STUART:

It could be all of those things in one. And it is the weekend, right?

MICHAEL:

It is like the mud out here. Some people are really having the best time of their life, and other people are not very happy about it.

STUART:

And now if you don’t like the weather, just stick around.

MICHAEL:

Yeah, exactly. Yeah. It’ll change.

STUART:

Hey, I want to go back to when you’re talking about structural welding. I know that in addition to all the found objects that you’ve incorporated, you’ve done some big structural steel. What was the throne on top of the gigantic tower?

MICHAEL:

Elevation. Yeah, yeah. It’s a 65 foot tall tower with a single chair up on the top throne. It said me and you would climb this piece and have your five minutes of fame and then are not even two minutes because there used to be somebody else that would want to sit in a chair, and you got to get down. Yeah.

STUART:

Was that your first time building? Like, kind of in big steel like that?

MICHAEL:

You know, I apprenticed for a sculptor when I was younger, sculptor named Louis. And then as who’s, American artist, pretty well known. He passed away some time back, but I got accustomed to the idea of building large scale pieces because you built large scale pieces across the country, and I was traveling and doing that, but I never thought that would have an impact directly on me.

So it was not a big transition to start to build, although there are learning elements. That come about. And, a lot of times you’re herding cats, running a crew, you’re having to work with big egos because that’s how it is. If you want to get qualified people and you don’t always agree, the design of that was through engineers.

Friends came up with designs and found a range aid and made this really fantastic jig that I was blown away by. It was like 14 feet long that we built all of the pieces around 12 of them, and then they all connected to each other and they all fit like I could never. I specialize in making things not straight. So there’s no way that I could have ever done that. And I was blown away when we connected all 14 pieces, and the last one was only an inch off and you just tighten the bolts. And I was like, wow. And it all broke down into smaller parts.

And my original thought was like, we’ll just build these things and we’ll go 60 feet tall. No, we have to have a system, unfortunately, to do it and transport it. I think that was back to the point of earlier career and doing festivals is you learn how to build things to come apart and go back together again quickly. And so the install takes a day. And so you can come to show up at the festival and build something, install something 65ft tall and then take it out in a day and put it on the truck and go.

And it allowed for transport of pieces across the country, or putting containers and go overseas, as opposed to building where I would probably normally build at that time. But you start thinking in terms of container size, how does it fit in a container? How does it fit on a 14ft two level for traveling under bridges? And what are your parameters?

And you build with that in mind. And it’s funny building things for the player. It was an education in how to modify I guess, or adapt rather because should go sideways here and you have to figure out how to get it done. And I remember the first time I did an install in a city or someplace, I’m like, we can go to a hardware store.

You know, it’s like we don’t have to reconstruct and rebuild. Luckily out here. Well, I need a certain type of tool to do this something. Well, the guy found one that’s on Jean, you know, 230 and somebody found one and brought it back, and you’re like, you’re kidding me. So you can modify so you learn how to build on the go and then places that are not ideal conditions where the ground is flat or you don’t have windstorms, rain storms or anybody that’s been here.

That was the story.

STUART:

Yeah. And increasingly there are angel artists who bring like their whole shop out here. So that tool is probably out here somewhere. But thinking like Iron Monkey, you see now they break so much, so much hardware out here.

MICHAEL:

Yeah. And they learn like, okay, we’re bringing the shop but it’s early days. What, what did you have? Good. We make it out of mud. Yeah.

STUART:

There we are. It was pretty much it. Yeah.

MICHAEL:

We can make it work. But all the things, I mean, we’ve come out here and, like, where’s the box of bolts? You know, the half inch bolts that connect the whole piece together? The 100 bolts. You’re like, “I thought you put them on the…”

“No, they’re in the shop on the table. I thought you got any. You figure, okay, what are we going to do?

And you source what you can and you find a way. You know, like, “Oh, somebody’s got a plasma torch over on the something. Let’s go cut these brackets that don’t fit by a quarter of an inch.”

“Oh, there’s 35 of them. We have to modify them.”

“Somebody’s got a torch.”

“Okay, great. We’re saved.”

But otherwise you’re like, what the hell are we going to do?

But yeah, the plywood provides, as they would say, the bounty of resources here has increased obviously, over time.

STUART:

So when you think back on all the projects that you brought out here, is there anything that just comes to mind is something that made you giggle? You look back on and think, that was really silly and I love doing it.

MICHAEL:

The first one was the Nebulous Entity, yet it was 30ft tall and I never built anything that’s 30ft tall. When we put the top on, I just was laughing because I’m like, oh my fucking God, that’s big. Because you can throw up numbers like, oh yeah, we’re going to make it 30 feet tall, but it was three stories tall. I laughed a lot.

Some pieces I cried a lot because it’s just like that did not work out how I would have wanted it to.

STUART:

Like which one?

MICHAEL:

Well, Babble. It was this tree, rotating pipe organ tree, that I built in the same year as that Happyland year, that I finished on Monday after the event. Um. I worked the whole week and had one day of fun, I think, and then finished on Monday. It was good because, you know, the hubris of, “Do you know who I am kind of can be, look, what I’ve done is resonating with you in the back of your head, and then you just get smacked in the face. And you’re like, oh yeah, your shit stinks like everybody else’s.

And it was humbling. And I’m glad it happened early because I learned. And it’s funny, over the years I’ve seen people that go big, and I’m like, yeah, I know that, I know that routine. You’re going to fail spectacularly. And they do. And they reach that point of like, I’m invincible!” I’m like, no… I didn’t really cry, but I was very sad.

But also every year, lessons learned or some kind of experience adapt and grow and expand from that.

STUART:

Fail forward, fail forward.

MICHAEL:

Yes.

STUART:

So I know what that made me giggle is. The sheep. The sheep. What did you call that one?

MICHAEL:

The sheep of mine?

STUART:

Didn’t you do a sheep thing like cloudy sheep?

MICHAEL:

No, but I’ll take credit for it.

STUART:

Okay. Cool. And then I’ll track that one down.

MICHAEL:

No. What did it look like? I probably know the people who did.

STUART:

It’s like sheep that were sort of like fluffy clouds.

MICHAEL:

Was it me? I made a piece called Drifts that were these swooping dendrites or something. But sheep? No.

STUART:

All right, moving on.

MICHAEL:

No. Now I’m intrigued.

I love when people would come up and like, “Michael Christian. Oh, yeah, you put that figure that’s…”

And I’m like “No, that’s not me. No, that’s that other guy. That’s another guy.”

Or somebody else would take credit for something that I had done. It all gets kind of mixed in the mash.

STUART:

Okay. I want to talk more about festival art. Is a phrase. I first heard that, like, ten years ago, I was talking to Kal Spieltech whose another artist who, you know, has feet in both worlds, right? Fine art.

MICHAEL:

Oh, yeah. Totally.

STUART:

And out in our world. And he told me that for years he was ashamed. Really. He hid is burning now, Art, because people dismissed it as, quote, festival art. Right.

MICHAEL:

Yeah.

STUART:

And it seems like the world is shrinking there. There’s a little bit more respect to the mainstream structure. We got to cover Sculpture magazine a few years ago. The burn. Yeah, it was the next big movement. Is there more respect in the mainstream art world, you think, for what we do out here?

MICHAEL:

It’s funny. I went to undergrad when Kal was in grad school when we were in Texas, so I’ve known Kal a long time, and I totally understand that because I did not align with the event for years. It was a double edged sword. You’re benefiting, but you’re also getting screwed because you’re just like, oh, you’re doing festival art. And then you settle into, you know, I’m just doing my art and I’m finding a way to navigate just what I’m doing, and for the reasons I’m doing them, I’m creating…

And people get to experience the work. And even Burning Man, I don’t align with all of their philosophies or ideas, but I appreciate the opportunity to bring artwork out and have thousands of people get to appreciate. And there’s not a lot of platforms like that. And festivals were an opportunity to do that.

And it’s quick, quick turnaround. Like a lot of the institutions or things that art festival are, you know, years! Two years, three years out are commissions that I do. It’s like oh, it’s gonna be 2028. I’m like, I can’t even imagine 2028. Where festivals were the immediacy of it, where it’s three months from now, and I’m like, “I’m down.” And the immediacy of people right there interacting with the work that you do. There’s no conduit they have to go through or they have to be a part of some. It’s like, oh, you show up and you’re there, you’re part of it. And so I do like that aspect of it.

But there’s festival art that, a certain type of work that is done, that I can see that people can criticize and marginalize. But the same thing in the art world, you know, a lot of the art world work can be categorized, and it’s really boring. That’s not to say that all the work that’s there is, but there’s a lot of it that’s the same as festival art, you know; there’s a lot of it that’s not interesting.

But I’m not one to judge either one. I like what I’m doing, and I try to stay in my lane and do what makes me feel good and what I enjoy, and it gets appreciated by those who do.

The first time that I came to Burning Man that year, I was like, what am I doing here? Because I’m not working in neon or flashing lights or fire. Yeah. And then I just had to go, well, no, I’m here to represent whatever the percentage is that I am here for, you know. Here’s my voice and I’m a part of the mix. I don’t have to be all of it, and take that on. I’m going to show up and do what I can on the side stage or whatever, but not the main stage.

STUART:

Well, that’s what I love. There is no main stage, well, except The Man, but…

MICHAEL:

Exactly.

STUART:

There’s so many side stages you can stumble into. Direct experience.

MICHAEL:

The best part about festival art, I don’t even know if it’s a category, but I… The little things that people do that are really compelling to me. They don’t have skills to do something or they don’t have the background, but they make something creatively and it’s just mind blowing.

You juiced that into being and it is great. It’s not big, it’s not massive. It’s just simple and thoughtful and quirky and clever and makes me smile. You know, there are a lot of things, the big projects, you can get bogged down in the heaviness of just building something, as opposed to like the whimsy of a quick end.

If you’re going to work on something for five months, you don’t want to get you want to space that out in a way so that there’s still some fun and you’re just not like, I have 10,000 more of these holes to make. So I would try to spread it out so that there’s always something like, I don’t know what I’m going to do, I don’t know what the top is going to look like. I’ll figure that out the last week. And then in the moment you’re like, “Haha, this is so fun,” and try to pace a project out.

And even on this project I didn’t know. The lids or some of the toilets in the end were the last week of the four months that I was working. You just leave something unknown so that you can kind of have some joy.

STUART:

Leave yourself some discovery.

MICHAEL:

Exactly. It’s like an adventure. A straight line to where you’re going is not a story.

I mean, we came in this year and we — for the first time in all that we were driving, 25 years — we got caught in the Gate. We were running late, and we had the 14 hour Gate experience. But at some point we just kind of surrendered to like, “Here we are.” And then you make due, and you make it fun. But to focus on, like, the frustration level; not fun.

STUART:

Humbling.

MICHAEL:

Humbling. Oh, and I love that part of building is that I’m not in control of anything. I’m along for the ride. And where is it going to take you?

And, I mean, weather is a big, big thing that’s really beautiful. It just smacks you down. You’re like, well, I talked to God, and that didn’t work out! So now I’m going to go along with what’s going to happen. Here we are.

STUART:

So what’s going to happen next? Are you thinking about next year already? I know you’re not a big advanced planner.

MICHAEL:

Any thoughts about next year we have right now would probably not be positive.

STUART:

Like don’t go!

MICHAEL:

Yeah. This is not fun. Why would I want to do that? And, luckily you kind of forget, I forget over time.

STUART:

Yeah, but ten months from now it won’t seem that bad.

MICHAEL:

Yeah. I think that, like we’re saying, every year is a new thing, a new project, and a new adventure, so I don’t think about it the… It’s starting something new. And so it’s an unknown territory and uncertain territory.

For the next year, I’m actually going to install some pieces in San Francisco.

STUART:

Oh, tell us about that.

MICHAEL:

A generous benefactor is on a mission to install a lot of sculpture in San Francisco. And with the help of friends of mine at Building 180, they’re helping to bring a lot of Burning Man works that have been around, and other pieces, that I’m installing in the city in various places. I’m going to put two pieces in.

STUART:

Stuff you’ve already built?

MICHAEL:

Yeah. A couple of pieces that were built out here, years ago, a piece called Corpus, and another piece called Bloom. We’re in the process of figuring out how to get them into the city.

STUART:

Oh, that’s wonderful news. Is your art installed publicly anywhere else where people might see it?

MICHAEL:

Publicly? Toronto, I have 2 or 3 pieces there. Canada. I’m big in Canada!

Reno. There’s several pieces in Reno.

I installed a globe in downtown New York.

STUART:

Tell me more about that. I’m really kind of fixated on globes these days. I want The Man to stand on the globe next year.

MICHAEL:

Oh, that would be fun. That’d be fun.

It was a version of a piece I made here called Home in 2010 that I got commissioned by a developer to build in front of their building. It’s like five blocks down from the MoMA. It’s a really beautiful area of town.

It’s out of stainless. It’s layers of city maps from around New York, that are layers that are illuminated in the center, and it rotates.

It was a version of a piece originally built here. I don’t know what the theme was that year, but the Home was the sculpture that I built. Another one of those that happened despite me. It was exactly what I wanted to build, despite me building it, kind of thing, you know. I had grander visions of it being something else, and then in the process, you’re like, well, why don’t we make it spin? And of course, it needed to spin from the beginning, but I didn’t have that so together at the beginning.

When somebody asks you the project name or title, some people have it all figured out in their head, but I don’t. I work more from just the general idea, or like I have a movement like, let’s do this direction. And even in drawings, they only taking so far. And then you start building and you get into materials. And the materials are like, no, that’s not really going to work. And you have to figure out a way to translate that and then construct it and build it. And so it turns out to be not what you would imagine; most often better than what I had imagined.

But yeah, the globe in New York has been there for five years now. I still haven’t seen it, because it’s in New York and I’m here, and I haven’t been able to get out. The original Home is in downtown Berkeley. It’s been there for seven years. It was supposed to be a year, and it’s been up for a while. I think that that whole ‘temporary art install’ thing works out well because it gives the place, the city or the municipality that installs it, the option.

STUART:

Right. Building temporary pads instead of permitted installation.

MICHAEL:

Well, yeah. And the people, it’s like, “Oh, we love it,” and then “We want it to stay here longer,” versus like, “Oh my God, please take that away. People are revolting.”

And it’s weird, when I installed Flock, which was a piece I did in 2001, in front of City Hall in S.F., I wasn’t sure how it would translate because it was built for the wind, you know, the plains of the playa where it’s vast and open. And so I wasn’t sure how it would work with buildings and other things, but it translated. I was really happy about that. That was my biggest concern. A lot of plop art is that way. It doesn’t take into consideration where it’s being put because you just drop it.

STUART:

Well out here, there’s so little context. And that’s a big plus for a lot of people’s imaginations, right?

MICHAEL:

That was the reason, a big reason for coming back every year is that it was a ‘no walls’ open space. There’s no front / back side, and it’s just ‘sculpture in the round.’ It was like the ultimate ‘sculpture in the round’ without any reference points or signage or context. It’s just like: What the hell? What is that doing here? What is that?

STUART:

And what can I do with it?

MICHAEL:

Yeah.

STUART:

Can I climb it?

MICHAEL:

For me building climbing structures was not necessarily the original intent, but I think that one the piece referenced earlier, the keyhole piece, was a piece called Orbit, and it was this rotating kind of creatures that were in this swarm around a piece. And people just destroyed it climbing on top of it; and got caught in it and would have to get removed. And, you kind of understand, okay, this is public art without boundaries, and people are going to interact at their own…

STUART:

The museum docents are not going to come along…

MICHAEL:

And they are going to do all kinds of things. I have friends who I asked, “What would you do?” And they’re like, “Oh, I’d totally climb up on that and jump up and down and swing.” And I’m like, “Oh, okay, well then I need to prepare for that.”

And at some point I built a series of pieces that were like platforms for that. They were kind of invitations for interaction in a way where the piece isn’t complete until people start to interact with it and activate it. And it’s a different experience every time because whoever’s there will be part of the process of.. Well, the piece was this when I was there because there were a bunch of clowns up on top of it, so it was a clown piece. But the next people come up, it could be something, something different.

There was a rotating globe we built, called E-POD. It was a giant, 22 feet wide by like 24 feet tall, and could hold 100 people on it. During the course of the week, there were fire spinners, performers. I got photographs later of, you know, all that spinning with fire performers on it. And then another one was hanging rope bondage things where it was spinning around with all these people on it. I went to stage one and then that’s as far as I took it, and iIt was open, you know. “Go for it. Have the experience and interact at whatever capacity and level you want to,” but building with the mind that anything could happen. And you want to be prepared so that it can hold that, because people get very enthusiastic.

STUART:

Hold those people, and in 50 mile an hour winds.

MICHAEL:

Yeah. Exactly. And when you take it to the city, you’re just like, well, nobody’s really climbing it. So this is a test in many ways. Can withstand the elements? Can it withstand the abuse? Can it withstand the interactivity that’s going to occur when you invite that there? You can’t really say, “Well, interact with it, but only to this limit.”

STUART:

I think Zac Coffin told me about engineering to the national playground standard.

MICHAEL:

I did a playground structure in Reno, I was over doing it because I’m like, “Really? That’s all your standards are?” I mean, I’m expecting… They had height requirements because they were more concerned about people falling. And I’m like, yeah, I get that, but we built it way… I’m used to like… We’re going to build this very strong.

And it’s interesting about that climbing structure I said earlier, the elevation, like nobody fell, nobody got hurt. And you would think by the way that people live in cities in fear a lot of times that, oh my God, somebody’s going to do something… They don’t. Something kicks in and they’re like, “This is a bad idea. I’m going to stop.” It’s a six and a half story tall climbing structure, and people are having a great time. I personally could get up about 14 feet and then I’m like, that’s about as far as I want to go.

STUART:

Bring me a cherry picker.

MICHAEL:

Yeah, I don’t like the heights. That’s not my thing. No.

STUART:

Alright. Anything else you would like to add for our listeners out there? Anything you want to say? How about two young people who are thinking, “Could I bring art to Burning Man?”

MICHAEL:

You know, there’s a lot… We were out installing yesterday, and a young guy came and he said, “Are you Michael Christian?” And I was like, “Yeah.” And he’s like, “I remember Drifts. I was 10 or 11 years old and came that year and I had a great time,” And it impacted him enough, he remembered. And, I was floored. He’s 20. I mean, what was that, 11 years ago? That was cool.

It’s interesting putting sculpture out. You don’t know the response because once you install it, you give it away, and you don’t know where it’s going to travel or what experiences people have. Only when somebody comes up and says, “Oh my gosh, yeah, I was totally influenced by that. That changed my world of thoughts around sculpture.” And I’m like, “Well, thanks for sharing. I had no idea.” You can have impact and you don’t even know it.

Any time I’ve intentionally wanted to have impact, it’s failed. I’m like, I’m going to make this so people will do this. No! People have their own experience. So the best scenario, I think, is when you build something and you get those responses that people have, and take it, and are inspired, and move on, and do something. And it’s really satisfying.

You find out later, somebody comes up and says something like “That totally had an influence on me.” And you’re like, “Wow, that’s awesome. I was just doing it selfishly to make art.” And we were talking about that earlier, that it’s a selfish act about doing the work. I want to make it, but it’s ultimately making it to share with other people. There’s a self focus or an intention that’s for yourself.

But also the ultimate reason for doing that is that you get to display it and share it with all these people, and join the other people that are doing the same thing. Burning Man’s pretty cool for that. There’s a lot of people that build things and you get excited. It was like the time of the year when everybody’s working on projects and you’re sharing information, energy, know-how, with all the other communities that are there, and with the sole intention of going out and sharing. And you get excited like, oh, so what are they building and what are we building? And we’re contributing. We’re part of a bigger community of people that are doing things to share with other people. And, that’s pretty… There’s a vibe that’s different than ‘I’m just building my art to see my art,’ you know.

I liken the climbing structures to like, open… A lot of sculpture is closed in a way where it’s like, “Look at me. Look what I’ve done.” I like the idea of having something be more of an open to interpretation and an invitation for somebody else to complete the sentence, as opposed to like, “Here’s my statement.” I like the open possibilities. It’s like evoking thought.

STUART:

I really love the idea of ‘completing the sentence.’ As a writer that appeals to me.

MICHAEL:

Yeah, yeah. Because I don’t know. They’re ‘complete the sentence’ for me, too. Like, I didn’t know what it was about until you just told me. Holy shit. This is about that. This piece in particular, Rosalie and a lot of others will come up and say, “Oh, no, it’s about this.” And I’m like, “Wow. You’re totally right!” And I would not have ever guessed that. I’m just coming from my lane: building. But if you hit on that, it’s really satisfying because you’re in the zeitgeist, you’re hearing something, you tap into something that’s broader than you are. And so other people can relate to it. And that’s magic when that happen.

And like I said earlier, kids come up and they’ll say something and you’re like, “That’s totally it. You crushed my ego again because I thought I was building this, and nope, I’m building something totally different.”

STUART:

I think we talked about “Why Burning Man?”

MICHAEL:

I think you have to question that and reevaluate it all the time because it’s not what it was. And I’m changing and I have to think, well, why do I still want to do that? So I think there is a constant “Why am I doing it?” all the time. It changes. The reasons I’m doing it now or definitely not the reasons I was doing it 25 years ago. The spirit of wanting to create is still there. But contextually, I mean, why would you continue to do the same thing or be at the same place and continue? This is 25 years. But I’m not going to stop making things, and this is an amazing place to share your work.

It’s a harsh environment, but there’s an opportunity to connect with a lot of people in your work, that doesn’t exist in other places. In the desert and whiteouts and things like that, traveling long distances to a barren wasteland, and in elements like this is not your first choice. But it’s a good choice oftentimes to share your work with people and connect with others. I’d say that’s why.

STUART:

You’ve been listening to Burning Man live. My guest has been Michael Christian. Thank you so much for stopping by, Michael.

MICHAEL:

Oh, thank you. This is fun.

STUART:

All right, take it away, Vav!

VAV:

I’m taking it, not very far, right here where we are.

You are watching… You are not watching Burning Man LIVE, the podcast with the odd cast, from the Philosophical Center of the Burning Man Project, a public benefit non-profit organization. We foster the global culture of Burning Man, bringing creativity, connection, and civic engagement into the wider world through arts, education, and social enterprise.

We thought a lot about this. We aim to inspire a more collaborative, innovative, and thriving existence beyond the annual desert event. Whatever part of that resonated most with you, is what you already do. That’s one way you help.

Another way you can help is to share some funds.

Money is the lifeblood of this labor of love, and money is to be circulated, not stagnated. Consider what you’d be willing to give, 1, 2, 5, 10, 100… once a month, once a year, once?

Now see how it works at DONATE.BURNINGMAN.ORG

It’s actually kinda fun.

Thanks to those who helped this one happen, from kbot to Brinkley, from Rosalie to the Burning Man webcast, and Burning Man Information Radio. Way to go.

I am the producer, Michael Vav.

And, thanks, Larry.